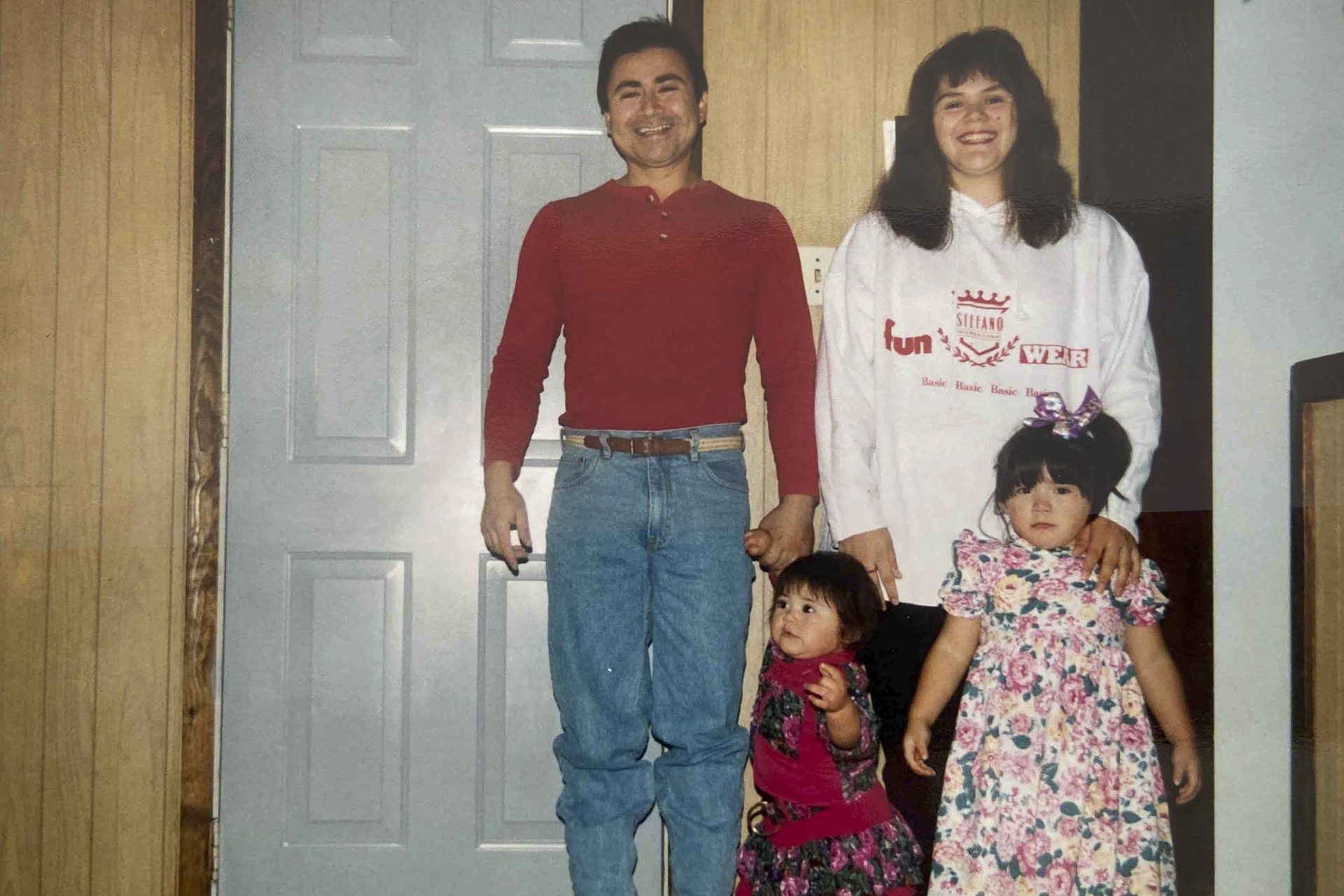

Photo courtesy of Vanessa Borjon

Photo courtesy of Vanessa BorjonA first-generation Mexican American on how her parents met through the Chicago Sun-Times personal ads and the benefits of dating slowly.

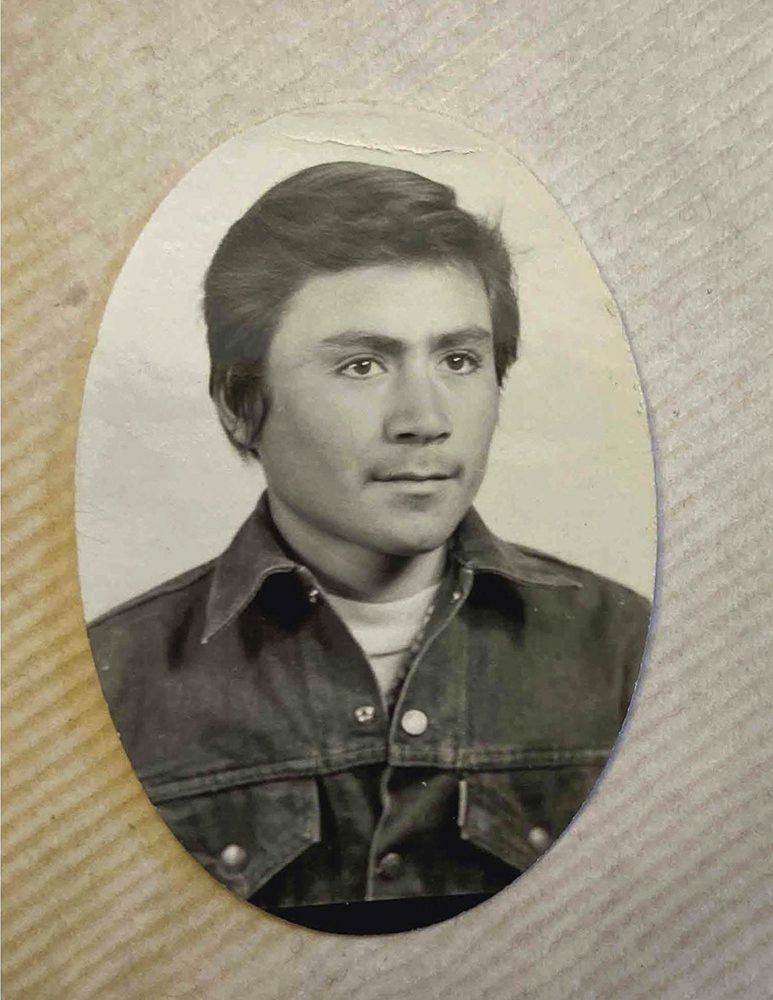

My father, Jose Juan, was born on a mountain in Mexico and brought into this world by a woman named Rufina. She was the midwife who lived on the land he grew up on in Zacatecas, and was by my grandmother’s side during her long, strenuous labor. Lobatos is a small town near the municipality of Valparaíso, with a population of less than 2,000. Nearly 1,800 miles away, in a small corner of northern Illinois, is Dekalb, the place my father would eventually move to with my mother to raise their three daughters. My father said it was fate that brought him to Dekalb, a town known for its flying ear of corn logo. He recalls seeing that same logo printed on imported crates in Valparaíso, and knew someday, the town would mean something to him.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

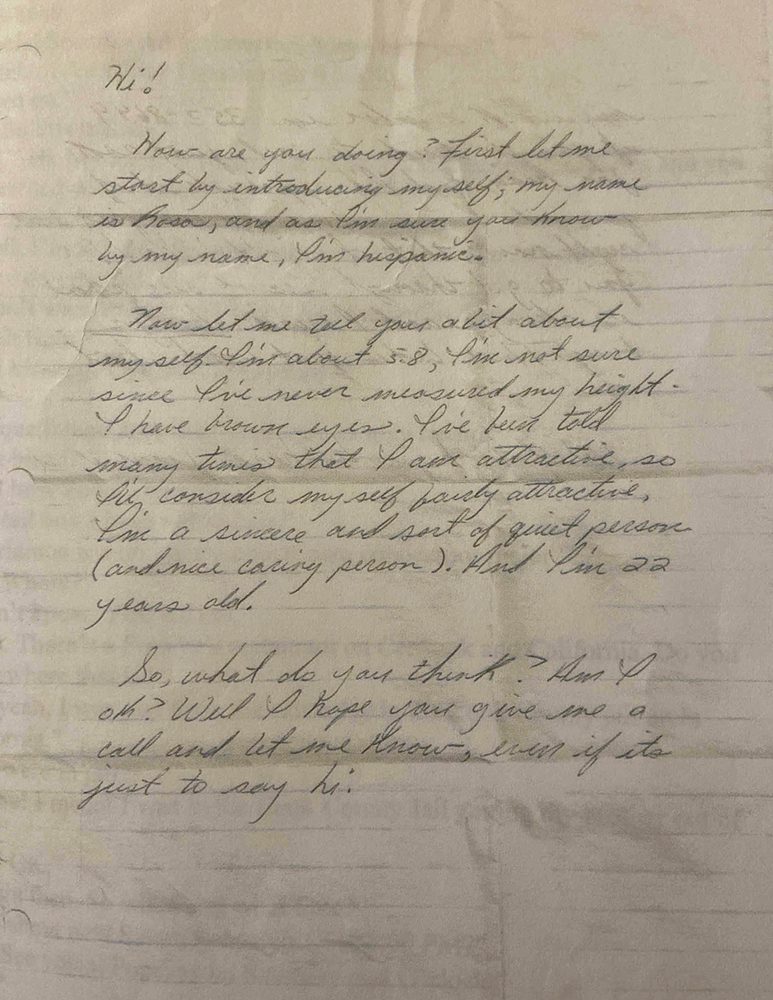

Fate worked its magic through the personal ads of the Chicago Sun-Times and brought together my parents, two very different personalities alchemized into one partnership. Approaching his late twenties and down on his luck with dating (and feeling growing pressure from parents who believed the eldest son should marry not only young, but first), my father had decided to seek a new connection using an ad. My mother, a native South Sider born and raised in Pilsen, responded to his listing with pressure from a coworker at her office job in downtown Chicago.

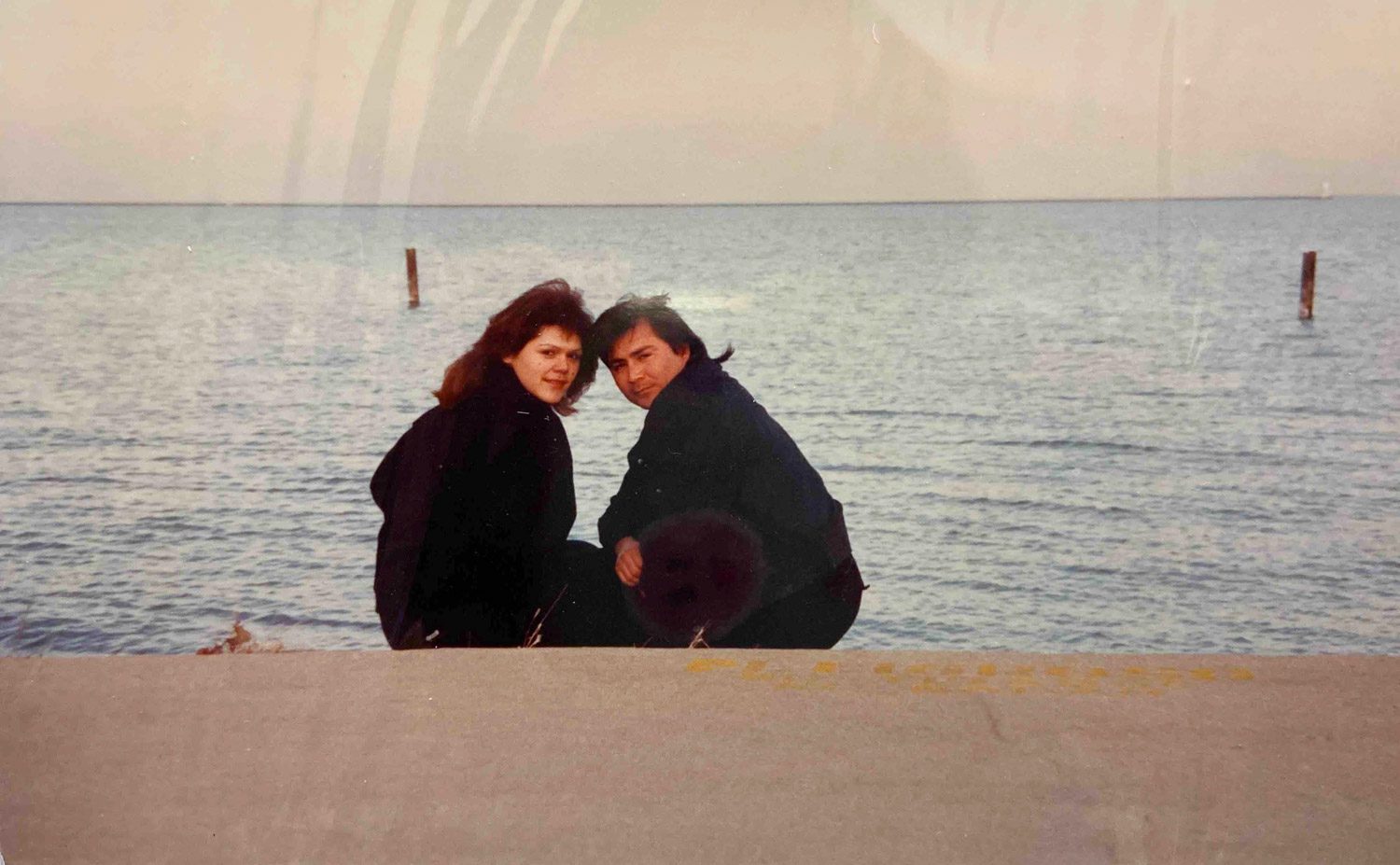

Their romance took off through letter writing. Although very different, my parents do have at least two things in common: a love of the written word and a rather introverted demeanor. In person, my father may be a man of few words, but through his letters he was able to capture my mother’s attention and heart. His letters were often signed, “Forever tu chato” (chato is a term of endearment for a person with a flat nose). After a while, they agreed to a date and met for the first time at the Popeyes on 26th and California.

As a first-gen millennial in my late twenties, I’ve learned throughout the years that dating is exhausting. Picturing my 25-year-old father slumped in the locker room of the factory where he worked, longing for connection but not knowing how to find it, I’ve felt some of that same isolation. Perhaps in the same way the personal ads in the Chicago Sun-Times felt like a last resort to meeting someone, so does creating a profile on a dating app.

In college, where my reach and view of the world expanded much farther than the confines of my rural hometown, I found myself curious about the popular dating apps my friends and classmates were using. I was using them with great success, swiping, matching and planning dates. But I was dissatisfied with them. Dating apps are built to appear and be interacted with like games à la Candy Crush or Words with Friends, which means they may not necessarily be built to create connection in a meaningful way. I often felt rushed to message someone back, exchange numbers or keep someone interested. Bumble users, for example, have only a certain amount of time to respond to a match before they disappear permanently from your screen. As quickly as someone could go from a match to a date to someone you tell your friends about, they’d just as quickly fade away into the forgotten trenches of your cellphone’s contact list.

Perhaps the culprit of my dissatisfaction — and what I can only imagine is a shared feeling among my peers, particularly BIPOC singles — is the interface of the dating apps themselves. OkCupid has a built-in feature to search for singles by categories like race, location and gender, which can be helpful but also exclusionary. Other apps use more insidious algorithms that filter users based on the data of how you use the app, which can mean that racial biases leave BIPOC singles further marginalized. But how could I capture the complexity of a dual identity as a first-generation child of immigrants?

Growing up in a small Midwestern town, I often felt my identity oscillating between the culture that existed within our household and the culture in my English-speaking classrooms. My classmates would use euphemisms I didn’t know, and when I’d use them incorrectly, they’d laugh and ask me, “Where are you from?” Although I grew up visiting family who lived in the city, I wasn’t a Chicago native like my mother. And as a first-gen on my dad’s side, calling Mexico my “motherland” felt a bit disingenuous. Existing in the middle, I felt alone, alienated and often like I was grasping at an identity I couldn’t even name, or one that didn’t belong to me.

Maybe my frustrations with dating apps were the same ones my father experienced when he considered posting his ad in the Sun-Times. In a letter he wrote to me and my sisters when my parents felt ready to share the story of their connection, he said, “Scanning the empty cafeteria during the start of my night shift at the factory, I saw a newspaper sitting on a table. It was the Chicago Sun-Times. I hated this newspaper! There was nothing interesting at all. Nothing but boring stories.” My father felt left out of the stories in the paper — invisible. This is a common feeling among immigrants: If we are reflected in the media at all, we are often squeezed into a monolithic narrative that we know can’t capture the fullness and diversity of who we are.

I’ve had the most success on dating apps when I’ve met people who have also valued the slowness of building a relationship — not even one that is necessarily romantic. Without realizing it, I was recreating the letter-writing romance of my parents. I had a previous partner with whom I shared a mutual love of writing, and throughout our relationship, we prioritized this slow form of communication. In this way, we were able to draw out our thoughts, yearnings and the everlasting stage of getting to know someone. That relationship has ended, but it is still a beacon of how I wish more of us connected: unhurriedly and with care. This ex-partner was also an immigrant, and perhaps we knew the best way for us to capture and share the completeness of who we are was through letter writing. That’s definitely not something you can do within the constraints of a dating app.

I find it funny, and perhaps the work of fate, that my current partner grew up in a town even smaller and lesser known than Dekalb, and less than 30 minutes away. Despite this proximity, our racial and cultural backgrounds are very different from each other. Growing up, he looked like his classmates, but I couldn’t say the same for myself. In the space between us, where our identities will never align, we are still able to get to know each other, and in turn, value each other. Although this relationship may add another layer to the journey of understanding my own self, its slowness feels liberating in how I am gathering answers.