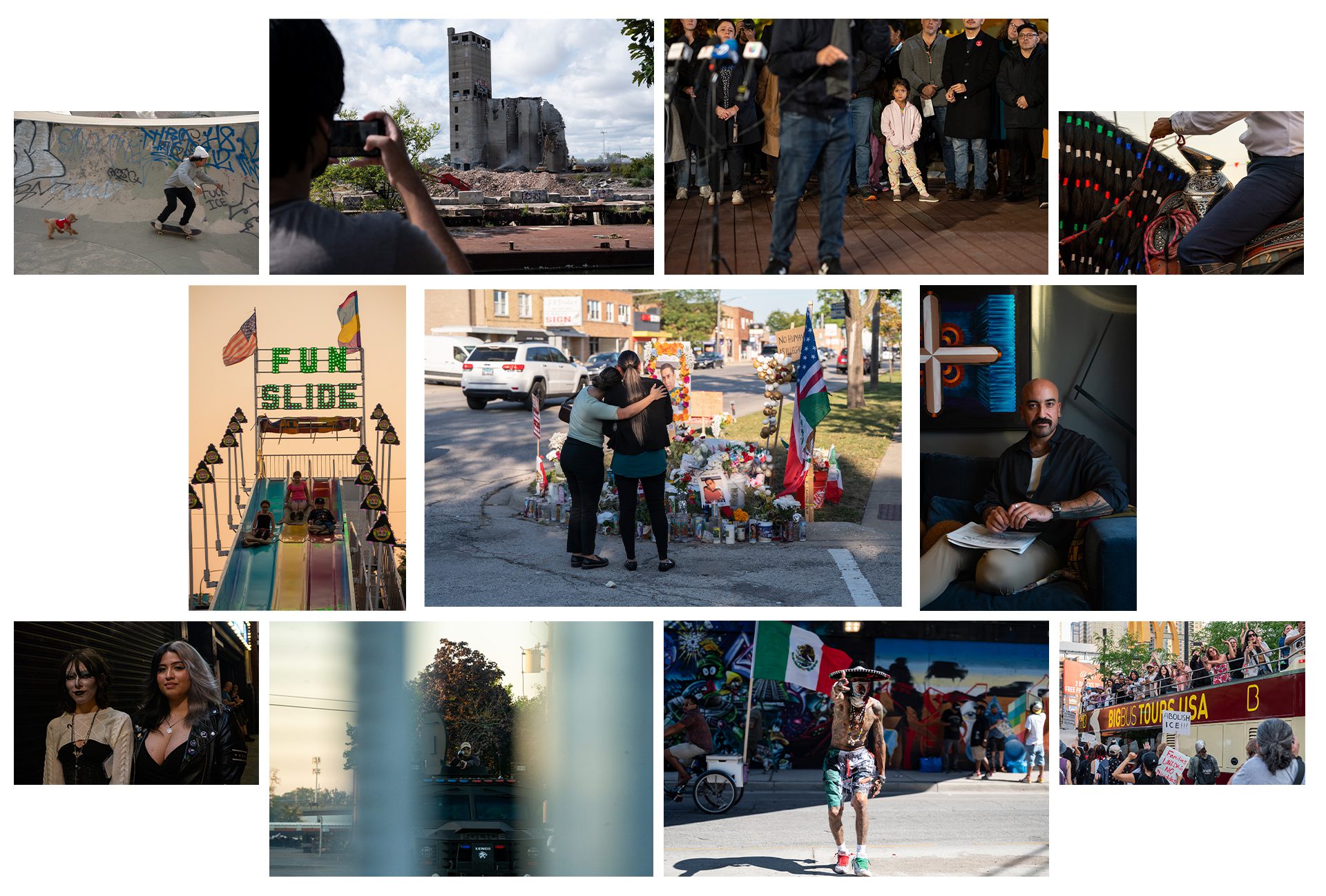

Photo collage by Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine/Catchlight Local/Report for America

Photo collage by Camilla Forte/Borderless Magazine/Catchlight Local/Report for America From a streetside vigil for a man killed by ICE to a rally for a daycare worker detained by immigration agents, Borderless Magazines’ visuals team discusses how they captured their top images of 2025.

The past year has been challenging for the communities that Borderless covers. Our visuals team consistently tried to strike a balance between respecting sources’ privacy and making human-centered work in the face of increased threats and deportations by federal immigration agents.

The aim was simple: highlight the people behind the headlines.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

Some of our favorite images this year were the ones that required the most thought and consideration. These include scenes from the Broadview detention facility, a demolition site, and family time at summer festivals.

We share a behind-the-scenes look at the approach we took to capture our 12 favorite photos of 2025.

This Q&A was edited for length and clarity.

Q: Photographing a vigil site can often be a pretty sensitive, difficult task. Why did you pick this composition?

Max Herman: This scene is from the week after Silverio was shot and killed by federal agents. I was trying to observe the street-side vigil and the way people interacted with it. Some people just hopped out of their car and stood by for a minute before leaving.

I didn’t want to swoop in on everyone, so I just pulled back a little bit to visualize the scene. I wanted to show where the incident happened, and I also wanted to get the whole vigil in frame. What happened was two women who worked at a nearby bank came, and they were there for a while. When I saw them embrace, it clicked that this is the moment.

Read the story: ‘This Could Have Been Anyone’: How a Fatal ICE Shooting Impacted Franklin Park Residents

Q: At protests, we often see people observing, but this photo in particular stands out because you showcase the connection between the protesters and the tourists on a tour bus. What do you remember about getting this photo?

Camilla Forte: The observation photo of people outside of a protest looking in entered my general visual vocabulary during 2020. We were seeing a lot of those images around that time. It would often be people out for a nice brunch who were met by this crowd of protesters, and you could see the dissonance there.

When I saw this scene in 2025, that was the first thing that came to mind. However, I think this photograph is a little different because it wasn’t so much a passive observation as it was an active participation. It’s in this very touristy downtown area of Chicago, and you get the sense of people who may be experiencing the city for the first time and encountering Chicago activism.

Read the story: Borderless Week in Visuals: How ICE Arrests Sparked Demonstrations In Chicago

Q: You spent a lot of time documenting the Ponce brothers. Wilson Skate Park was a focal point for their work and where they spent a lot of time. This particular photo gives me a sense of home. What was it like photographing them there?

CF: I wanted their portrait to capture where they felt the most comfortable. Javier Ponce immediately chose Wilson Skate Park, where he learned to skate and spent much of his time when he was younger. This photo shows just that.

They’ll just bring Benny the dog into a bowl and skate with him, trusting the community around them. The dog has been at the skate park long enough that it’s comfortable running after Rodrigo on a skateboard and knows that it won’t be stuck in a bowl forever. It showcases a lot of that comfort and the elements that work to make this place home for them.

Read the story: Boards Across Borders: Two Chicago Brothers’ Love Letter to the Guatemalan Skate Community

Q: What drew you to photograph this child specifically during the North Center Rally?

MH: This happened on the day that a daycare teacher was forcibly taken out of a nearby daycare by federal agents. The community rallied en masse that evening at North Center Town Square. I’ve never seen that many people in that square. I saw reports that there were over 1,000 people.

I noticed that the rally was adults talking. There were also many children there. Some of them looked confused, others looked tired–some looked interested. There was one girl on stage. She seemed to be listening but also concerned. I sensed a mix of emotions. I was thinking the rally was about the safety of children, but we weren’t hearing from them. I focused on her as she watched the speakers.

Read the story: ‘It’s Shameful and Embarrassing’: Chicago Daycare Worker Arrest Leaves Families on Edge

Q: You covered Fiesta del Sol as many other summer festivals were cancelled because of heightened immigration enforcement. You were able to capture joy there. In this particular frame, what was it like documenting these moments where it seems like people were able to enjoy themselves?

CF: Capturing these images was particularly important for me, contrasting the tension we heard about and witnessed this summer. Even in difficult times, there is a contrast where people still want to maintain a level of normalcy for their children. People were tense, but they had wonderful memories from their childhood. Fiesta de Sol has been around for decades and parents wanted to make sure their kids experienced what they remembered from their own childhoods.

Read the story: How Summer Festival Organizers Leaned into Community Resources to Resist ICE

Q: Can you walk us through the process of capturing the groups monitoring the demolition at Damen Silos?

MH: This was an interesting story. It had been in the works for a while, so I was able to visit the site before this particular day to see the progress of the demolition. This is a very historic site, but there are environmental activists who regularly went to make sure things are going as they should be.

In this particular photo, Ajay Chatha, is closely documenting with his phone in the demolition process. I wanted to show him documenting [that process] and how important it is to have a record of this because we’ve seen that demolition processes can be problematic environmentally if no one’s watching or if no one’s holding them accountable.

Read the story: Environmental Advocates Keep Eyes on Damen Silos As Demolition Resumes

Q: During the summer, you covered an anti-ICE goth show fundraiser. Can you describe how you set up this portrait and what it was like working with the organizers behind this movement?

CF: This is one of the first stories I pitched after joining Borderless. Alternative culture in Chicago has an activist undertone, and these young women were blending the alternative scene with issues affecting their communities. They told me the goth scene — which has a significant following among young Latino people— was impacted by ICE enforcement. I wanted to showcase this and highlight who was leading the effort.

Read the story: Chicago’s Goth Artists Support Immigrants Through Their Music: ‘We’re…Fighting the Good Fight’

Q: In Broadview, one of the people you were following was Joaquin Martinez and you were honing in on details. The fact that you captured this evolution of adaptation to the changing situation was pretty remarkable. I wanted to ask you about your attention to detail and your persistence in following through to see if anything changed. What was your approach in that?

CF: At the time I took the second image, I had been going to Broadview for over a month and had gotten to know Joaquin [Martinez]. He always wore this giant rosary across his whole body. I had seen him attach things to this rosary as time went on—at first, it was just goggles, sometimes it was just a mask. That day, he had both. I vaguely remembered making this image before, but I didn’t know that I had gotten the framing so spot on until I got back and reviewed the photos.

Read the story: Religious Activists Protested Broadview for Years. Now, ICE’s Crackdown Is Drowning Out Their Prayers

Q: You mentioned before that this scene wasn’t necessarily a part of the South Chicago Mexican Independence Parade, but more on the outskirts. I’m curious why you felt it was pertinent to photograph it as you did?

MH: The parade in South Chicago passes through various parts of the neighborhood on Commercial Avenue. There’s one stretch where it crosses a lot of viaducts and that is the home to the Meeting of Styles graffiti festival.

Edward, a known figure in the lowrider and art community, was there at the festival on the street. At the same time, a vendor with a Mexican flag passed by on his bike. It came together as the parade was passing. It was an interesting intersection of two events.

Read the story: Mexican Independence Day Parades Celebrate Heritage, Despite Immigration Pressures

Q: Can you talk about honing in on the details at the parade? This saddle, in particular, was framed well—you get a little bit of everything in the scene while still being able to zoom in and capture the textures of the moment. Did you look for wider scenes before this?

CF: I had been following the riders throughout the parade and getting photos of the crowd interaction, but I knew I wanted to make some detail images going in that day.

Ranchero culture is a significant part of Mexican American identity, and the tradition of braiding the horse’s hair is very common in these spaces as a way to care for the animal. I focused on this horse’s mane because I thought there was a lot of interest in the Mexican flag colors, and it served as a nod to heritage and tradition.

Read the story: Mexican Independence Day Parades Celebrate Heritage, Despite Immigration Pressures

Q: You seemed to pay close attention to the environment of Toufic Alayyash’s home office, including the art, the lamp and his sketchbook. How did you go about posing Toufic and composing this portrait?

CF: Toufic’s home was meticulously designed, so it was honestly an embarrassment of riches in terms of setting for the portrait. However, I knew I wanted to highlight his bold color choices and careful use of space, so having him sit on the couch, where I could incorporate the architectural detail of his lamp into the composition, felt like the most natural way to do that.

Read the story: How a Queer, Lebanese Immigrant Found His Home