Eli Ramirez/City Bureau

Eli Ramirez/City BureauRecently arrived migrants say they want to find jobs and build stable lives for their families, but the roadblocks they encounter make it extremely hard to get ahead.

This story was originally published in City Bureau.

They’re eager to work. They bring a host of skills and experience, including in higher education, banking, construction work, clothing design and mechanics.

Still, recently arrived migrants are struggling to find work.

Like other immigrants before them, many are turning to day labor or one-off jobs. The process of obtaining work authorization, they say, can feel murky and requires patience — with no guarantee of ever getting approved.

News that puts power under the spotlight and communities at the center.

Sign up for our free newsletter and get updates twice a week.

But, as more than a dozen recently arrived migrants told City Bureau, getting that authorization and finding a job is paramount to getting their footing in Chicago and reaching economic security.

Until then, many are finding jobs through a combination of word-of-mouth or waiting at sites where contractors hire day laborers. When they do find work, there are times when they get paid far below minimum wage — or not at all — and face threats and intimidation.

City Bureau’s Civic Reporting fellows visited two South Side neighborhood spots to connect with recently arrived immigrants and learn more about their search for work.

Editor’s note: Interviews were conducted in Spanish and translated into English. Interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Para la versión en español de este artículo, haga click aquí.

Chicago Art Department, Pilsen

A few blocks from the largest city-run emergency shelter for recently arrived migrants, a stretch of Halsted Street in Pilsen is bustling. Parents are dropping their children off at a nearby neighborhood school, while others run errands or head out to find work as they pass to and from their temporary home.

Andris Rodriguez, 36, is from Venezuela. She is living at the Pilsen shelter, and her two children — an 11-year-old son and a 6-year-old daughter — attend a nearby school. Her son is anemic, and she worries about his health. Rodriguez plans to move into an apartment with her family by the end of February.

What would make you feel comfortable in Chicago?

To find a job. I want to be able to support my family here and back in Venezuela. My mother depends on me.

What was your profession in Venezuela?

I used to work at a bank. When my job wasn’t cutting it anymore, I sold clothes on the side with my husband. We stayed in Venezuela as long as we could, but it got to a point where we had to sell our belongings to come to the United States.

What would you like to tell people who might come across your story?

Have empathy. We didn’t come here to take anything away from you.

It’s been difficult for my kids to adapt. There are days where I blame myself for everything my kids are going through. I want them to understand this will be good for us in the future.

David Cegobia, 30, is a construction worker from Venezuela. He is currently living in the Pilsen shelter. He doesn’t qualify for Temporary Protected Status, as he arrived after the Department of Homeland Security’s July 31 cutoff date. He hopes to find a job so he can move out of the shelter. He has found work in Chicago on just four days since he arrived in December with his wife and two daughters.

What methods do you use to find a job?

I take the bus and walk. Whenever I spot construction work, I’ll ask if they are looking for someone. I’ve only worked four times, and I got paid only $25 a day. They take advantage of us because we’re migrants.

Other migrants in the shelter let me know about possible jobs, but [companies] don’t hire me because I don’t have a permit. My wife worked at a bar for one weekend. In Venezuela, she worked as a nail tech. I sometimes wait outside the shelter, because some [employers] will come looking for people to work.

Why did you decide to migrate to the United States?

I came here for a better future for my family. My salary in Venezuela couldn’t even [cover the cost of] a carton of eggs. But I did have to leave behind my father and siblings in Venezuela.

Why do you want to work?

I would like to work because I want to hire a lawyer to help me apply for permanent asylum. At the shelter, there are case managers, but the process isn’t organized. I’m desperate, and the lack of assistance makes me stressed.

Robert Araujo, 30, is a mechanic from Venezuela who lives at the Pilsen shelter with his wife and 7-year-old son. He was approved for TPS and work authorization and hopes to study mechanical engineering.

How do you find work?

Some [recent arrivals] say they can’t work until they have a work permit. But if you really want to work, you’ll do anything. In Denver, I worked with a Mexican mechanic for a month and was able to save up for my own tools and a car. I found work on my own by posting my services on social media and got jobs that way.

What would make you feel more welcome?

I’d like to have steady work and maybe buy a house. But you can’t be sure of a future here, because tomorrow, if a judge or immigration [officials] or the president decides, they can force us all out.

What do you want people to know that’s not covered in the news?

If people are stealing shoes or jackets to sell, or food, it’s out of necessity. It’s not because they want to do it, but because of hunger. If they had the permission to work, it wouldn’t be happening. People want to work but they can’t. There are many solutions other than stealing and ways to find work, but you’ll do anything for your children. They don’t see another option.

Concord Missionary Baptist Church, Woodlawn

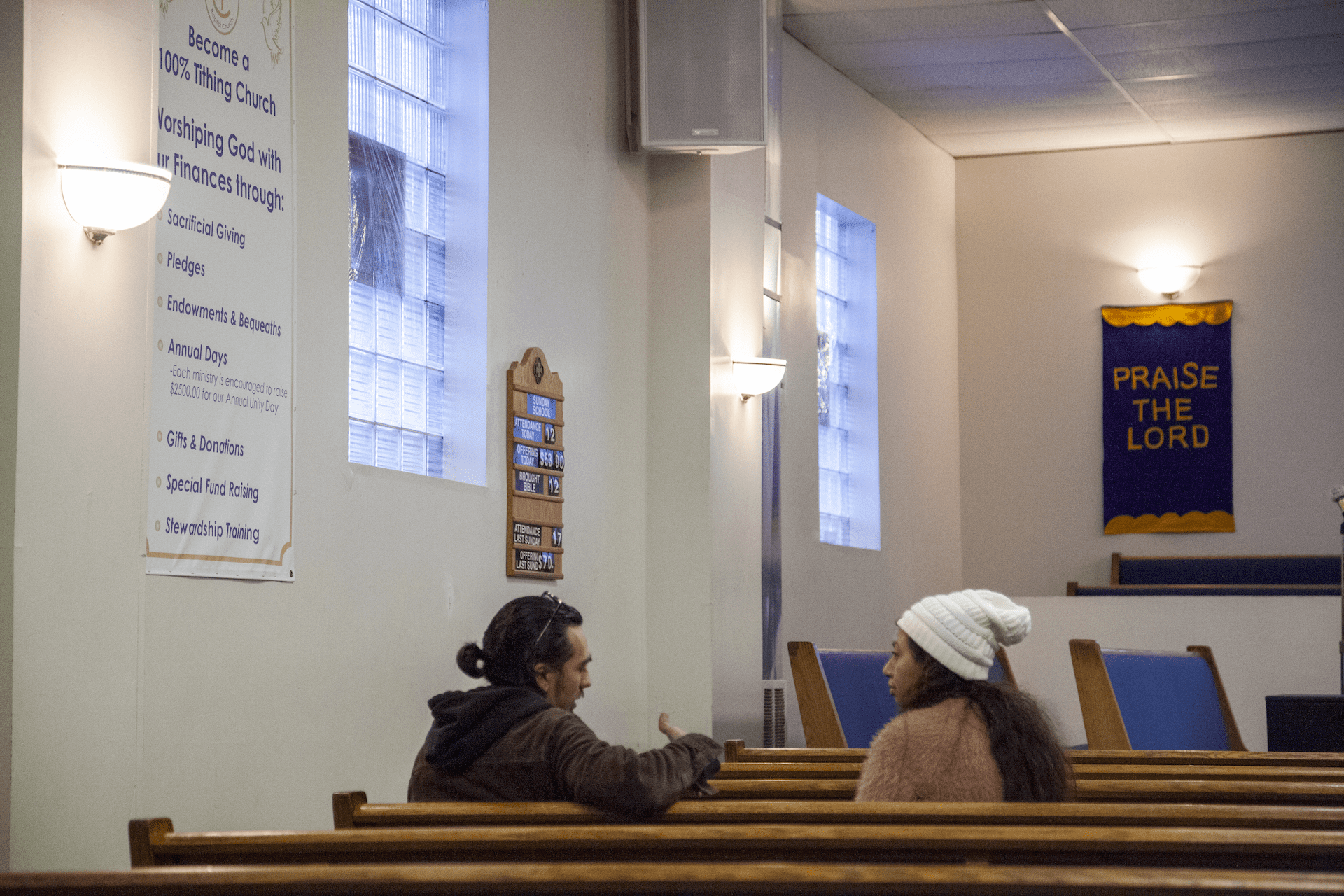

At Concord Missionary Baptist Church in early February, asylum-seekers gather in the large sanctuary for the church’s first Spanish-speaking Sunday service. The pews are bright blue and brown, and almost half are filled with first-timers who are staying at the nearby city-run shelter inside the University of Chicago Charter School on 63rd Street. After the service, many stayed to receive luggage and winter clothing from Concord’s makeshift free store.

Freddy Manuel Palmar Palmar, 25, is a soon-to-be dad searching for work. His dream job would be to find work in a garment factory in Chicago, as he used to design jeans in Colombia before coming to Chicago with his wife, who is 8 months pregnant. Palmar recently moved into an apartment, and he is most concerned about how he will afford the $1,400 rent without a secure job or a work permit — and with a baby on the way.

What are you doing for work?

A little bit of everything right now. A man is paying me to fix his car and garage and organize things. I am helping him with the construction and demolition. It’s difficult for me to find permanent work or even a day job. I went to the Home Depot [parking lot] for seven days straight, and I didn’t even get a day [of work].

How much are you getting paid?

I started at $100 per day for 10 or 12 hours of work. Now, I’m getting $80 a day. I’m not sure how much I will get paid moving forward. I can’t negotiate, because I’m too easy to replace. There are too many people [looking for work outside] Home Depot to say, “Boss, $80 is too little for this work.”

Read More of Our Coverage

Can you describe your process of searching for a job?

I usually get to the Home Depot by 6 a.m. I’ll wait for someone to come and offer me a job. If I’m lucky enough to get a job, I will work that day.

What’s the most they’ve paid you?

The max I’ve gotten is $120 per day, which is good for me, but I’ve been like a worker bee. Other times, I’ll work long days and only get $50.

What was the work environment like at these jobs?

There are some good people there. Sometimes I get food. There was a situation where an Ecuadorian man wanted me to unload a box of concrete from his truck, and I worked with another guy pouring cement. I spent a lot of time working there, and at the end of the day, I only got $50. It was from 7:30 a.m. to 5 p.m., and I ended up crying. It felt like abuse.

Have you ever been threatened when working these day labor jobs?

There was one occasion when a guy wanted me to unload some stuff from his truck, but he was in a bad mood, and I got a sense that things weren’t going well for this guy. Then he got mad and kicked me out of the car and made a sign with his hands threatening to shoot me. I didn’t want to get back in the car, so the guy left me there.

What would be your ideal job here?

I spent four years in Colombia working for a company designing jeans. I know a lot about them, and I would love to work on that. I know how to work with all the machines.

Jhovany Jimenez, 42, is a biology professor from Venezuela. He left because faced political persecution for participating in protests after noticing corruption in the university programs he managed. He worked on his own asylum application and was recently approved. He lives at the Woodlawn shelter with his brother.

Who has helped you while you’ve been in Chicago?

I’ve received housing benefits from the Catholic Charities program and found an apartment. I want to be able to be independent and leave the shelter and am in the process of moving. I’ve found free furniture and appliances through the church and group chats. Centro Romero helped me apply for my work permit in July.

How have you been looking for work?

I’ve had a work permit since August. I want to work so I can contribute to the nation, to the city. I met an alderman recently and wrote him a letter to let him know that, based on my background, I could participate in the city’s development. I haven’t heard back from his office yet.

What kind of work do you want to do?

I have three degrees in natural science, a postgraduate degree in education planning and evaluation, and a master’s degree in education. I want to work in curriculum development or education more than anything. I have experience volunteering at shelters, which I like, because I have a social background. I’m also fit to work with the same agencies that help migrants, since I can help with immigration forms.

Have you been able to find side jobs?

Jale? Side gigs? Of course one finds a way. I’ve gone to Home Depot and have found some gigs painting, doing demolition, moving. I’ve also driven people places. I was able to buy a car by saving little by little. I used to get around the city by foot, but my feet would blister from how much I was walking. First I bought a bike, which made it easier to get around [for work], and now I have a truck.

Alberto Pinto Jaikher, 34, a former teacher and small business owner in Venezuela. The soon-to-be father arrived in Chicago in January with his partner Sheila Rondón, 20, because Jaikher has a brother in the city. The couple lives in the University of Chicago Charter School shelter in Woodlawn.

When did you arrive in Chicago?

Alberto Pinto Jaikher: We arrived in Chicago on Jan. 8, but got to the United States on Jan. 2.

Right now, we have not participated in the legal process because we didn’t get here earlier. When we entered [Chicago], we didn’t have benefits, and we didn’t know how to get a work permit. They told me that first, we had to apply for political asylum. But right now, we are in the shelter waiting for the government to help with that.

I came here to work, to strive and acquire things for ourselves. That’s why I believe the majority of people want a work permit. There are many people at another shelter that are receiving that. In all reality, we have received very little at this shelter.

Have you received any benefits for the baby?

Sheila Rondón: They provided some appointments for the dentist and an ultrasound. And they gave me an appointment for my due date.

APJ: But now, the only thing we are asking for is help. Not help with money; help with the papers. Like, “Here is your permission to work, and here’s a job.” When I first got here, someone ripped me off. I went to work for a few days shoveling snow near Casa Esperanza, [a shelter in South Chicago]. And on the second day, they told me, “We aren’t going to pay you.” I spent all night and all morning shoveling. When I called him, he said no, it was a legal issue. They didn’t pay us.

In the state of Illinois, oral contracts are as binding as written contracts. Do you know if this happened to anyone else?

APJ: Near Casa Esperanza, yes. Three others who worked with the same person. I couldn’t tell you where we were or the address, because he recruited us from the shelter and took us to distribute the salt and shovel snow. Here, all the houses look the same. We worked all night, and he wanted us to work more than 15 days.

What are your hopes for being here in Chicago?

APJ: The truth, as they say, is to build a life. We came here with a different plan: to work and, well, you see, she’s pregnant. And we want to live and have stable work.

SR: We don’t know if [that American dream] is the truth or a lie. To be honest, that’s what we want to know.