Susan Adeeb came to the United States as a refugee from Iraq. During the Iraq War, she served as an interpreter for the U.S. Provincial Authority.

Susan Adeeb came to the United States as a refugee from Iraq. During the Iraq War, she served as an interpreter for the U.S. Provincial Authority, and then as a political assistant for the U.S. Embassy. She says it was a job that brought her both joy and fear.

Susan sat down with Borderless to discuss the dark years of 2006 and 2007 in Iraq, which left thousands dead and four million displaced. Now a U.S. citizen, Susan works as a refugee case manager for seniors at the Iraqi Mutual Aid Society, a nonprofit serving the Iraqi refugee community on Chicago’s north side.

When I worked at the U.S. Embassy, every month Iraqi staff members were kidnapped or killed. My role there was as a liaison between Iraqi government officials and the U.S. Embassy. But in a job like that, you suspect everyone. It was a life of guessing someone’s secret agenda paired with this constant level of skepticism. At the end of the day, you never knew these politicians’ agendas.

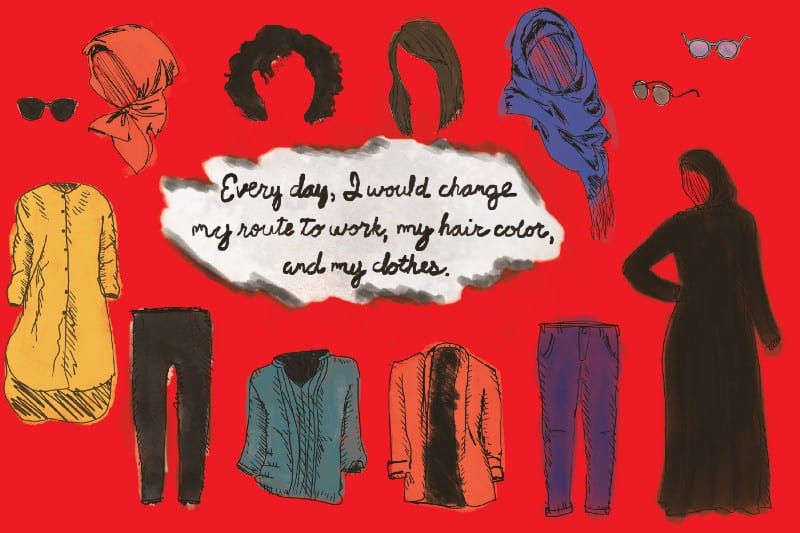

I tried to hide my work, even my identity. Every day, I would change my route to work, my hair color, and my clothes. Sometimes I would wear a scarf or glasses. I would sell my car or exchange it for a new model, all so that they couldn’t get me. It wasn’t a stable life.

One day, an Iraq parliament member asked me, “Where are you from?” Such as simple question, right? At the time, I lied and said, “I’m from Michigan.” Changing my identity even then was the only thing I could do to protect myself, so he wouldn’t look into who I really was, which was an Iraqi.

I did many things like this to throw people off my trail, not because I heard bad things, but because I saw many bad things in those years. I saw many dead people, and I lost many friends.

Many things happened to me, but my asylum journey began one day when I opened my computer at work. Yahoo! Messenger popped up and a message said, “You are feeding your children with dirty money. We will cut your head off.”

When I read this message, my breath disappeared.

Later, a man came to our family home and talked to my mom. He said, “Do you know where your daughter is working?”

My mother yelled back, “Why do you care where she is working?” He informed her that I worked at the palace, which was in the Green Zone.

“Give me money and I will be silent,” he said.

At the time, my own mother didn’t know where I worked. I never told her. You have to understand that this wasn’t a time where you could really go and work with the Americans. My mom was pissed off and she said, “Go away!” thinking that this was just a fake blackmail threat. Later, she found out the truth. I had been working with the Americans.

Other times, incidents stalked you like ghosts. There was a man standing in the middle of road riding a motor bike, just looking. Just seeing his face prevented me from going home. I tried to shake him off my tail and only returned home at night. There were many things like this that happened. The situation was so bad in the end of 2006.

But January 30, 2007 is a day I will never forget. Our house was hit by a rocket. We had invited our aunt’s family over for lunch, and just retired to the parlor after a family meal. We heard a huge explosion just outside the window from the dining room. All the house’s windows shattered. I guess if we were still eating we would have all died that day.

At that time in Iraq, and even today, Iraqis didn’t have regular lives. You would go outside to find a dead body in the road, or a body thrown in the trash. It wasn’t life actually. It was a nightmare, and whenever you remember these memories you feel nervous. I don’t like to remember, actually.

The dark years were 2006 and 2007. We lived in a Sunni neighborhood called Adhamiyah. It was a considered a hot zone by the U.S. Embassy, and some of the houses were really controlled by Al Qaeda. They would bring hostages inside these houses, then throw their dead bodies in the street. Some militias started killing Shia people who had lived peacefully in our neighborhood before this war.

One of my worst memories was what happened to a neighbor who was Shia. She was threatened that if she didn’t leave our neighborhood, she would be killed. So, she brought six men with her to move her furniture, really just as an effort to go along with their demands. Then suddenly a car stopped with masked men, and shot her and the movers to death. They were moving, so why would you kill them?

That night I remember coming home and walking by her house. I’ll never forget seeing one of the gunmen’s masks thrown on the street in a pool of blood. That night I couldn’t sleep. I felt this pain in my stomach that felt like fear and anger at the same time about our situation. When you experience things like this, you don’t know what to do. I found myself looking in the mirror before work everyday, thinking to myself, “Is today the day I will get a bullet?”

It was a hard life, really. You think back sometimes to memories about how someone at the mosque in our neighborhood would jump on the loudspeaker and scream, “Allahu Akbar” because some Shia militia was attacking our neighborhood. It’s so crazy that you have a sectarian militia coming to your neighborhood, to your homes to kill you, and all you can do is sit in your home. There was no government, no one really, to protect you.

But still, I think when we talk about sects, it wasn’t really Sunni or Shia, but just people with agendas. Iraqis weren’t ever sectarian before the war. Our families were mixed. In my own family, I have a sister-in-law who is Shia, and we are all Sunni. If we couldn’t get along, how would this happen? Honestly, we never thought through this sectarian lens before 2006.

Whenever I remember it, and I talk about it, I’m not emotional. But, then I think, if I couldn’t come to America, what would have happened to my daughters, who were just teenagers at that time, or to me?

The final straw was when I had to keep my daughters at home out of school. One of my girls did an exchange program in America, and when she returned in 2005, she told me, “Mom, whenever I speak, everyone will look at me this certain way including the teacher.”

They all knew she had been in America. She didn’t feel comfortable anymore. I heard that some girls were kidnapped, raped, and killed, so I was so scared to lose her. I couldn’t lose my girls.

Some people are still there in Iraq, but it isn’t safe. Since I left, I have never thought of going back, and honestly I don’t want the connection any more because it is just a place of fear for me. All my close family is here now, and after my father and grandmother died, all my connections are gone.

Refugee life feels a bit like being reborn. It’s a strange feeling. I was so happy when I finally came to America that I didn’t know what to do. From the beginning, I felt a part of America, and today we are all U.S. citizens. We have built so many things here through hard work, and even 10 years later every day we are working and studying to improve ourselves. One of my girls is an architect, the other one got a job in the government as an investigator.

The fear that Americans have of people from the Middle East is not right. Iraqis and Syrians are not dangerous, but like everywhere there are criminals among them.

One of our friends from Iraq, who is U.S. permanent resident, was detained at O’Hare International Airport for 8 hours during the immigration ban. Eventually, he was let go. But still, there is no respect for American law when you issue a green card, and then you stop or detain a green card holder. It’s contradictory.

In the end, this country was built on immigration and refugees, who brought different cultures and ways of life. Diversity here is what’s important. It’s what you find in America that you don’t find in other countries. In the end, we come to make America stronger. We came looking for better lives. Why change it now?