Brian Herrera for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

Brian Herrera for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local Cómo es ser un chef queer e indocumentado en Chicago durante la pandemia del COVID-19.

El chef Arturo Barbosa nació en Guadalajara, México, y actualmente vive en el barrio Pilsen de Chicago. Cuando perdió su trabajo en un restaurante durante la pandemia, decidió ofrecer comidas caseras en su barrio.

Las industrias de servicios de hospitalidad y alimentos a menudo dependen de trabajadores indocumentados, sin embargo muchos de ellos no tienen dónde acudir cuando quedan cesantes. Una vez que estos trabajadores pierden sus empleos, usualmente son excluidos de los programas federales de ayuda como los beneficios de desempleo, resultando ser un grupo severamente afectado por las consecuencias que conlleva la pandemia.

Pero los inmigrantes indocumentados como Barbosa encuentran maneras de superar los desafíos que esta crisis de salud global ha creado. Barbosa habló con la revista Borderless sobre sus experiencias durante la pandemia.

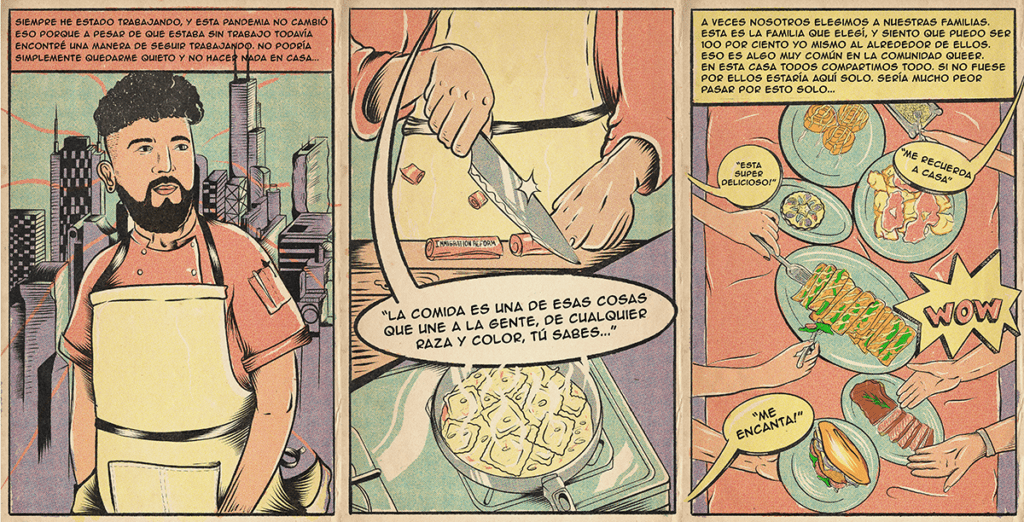

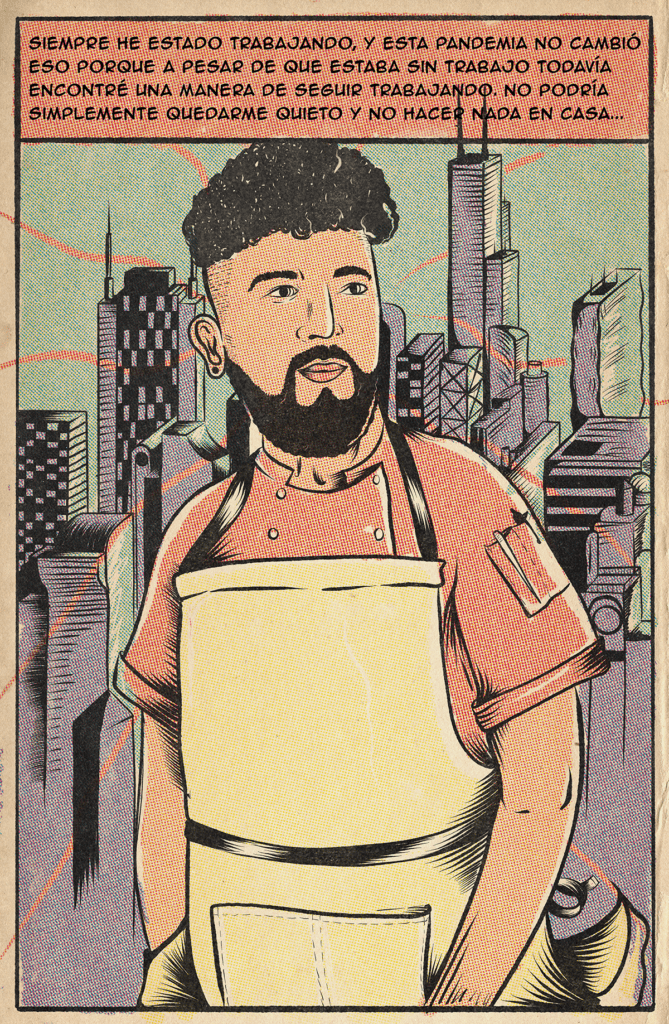

Siempre me enseñaron que uno debe trabajar. Es una de esas cosas que me inculcaron desde que era joven. Siempre he trabajado y esta pandemia no iba a cambiar eso.

A pesar de que estaba sin trabajo, no podía simplemente quedarme sin hacer nada en casa. He trabajado en restaurantes básicamente toda mi vida y siempre he admirado a chefs por todas las cosas que hacen.

Pero quería hacer lo mío. Me encanta que mi cocina sea muy única y reúna a la gente en una mesa donde puedan charlar.

Brian Herrera para Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

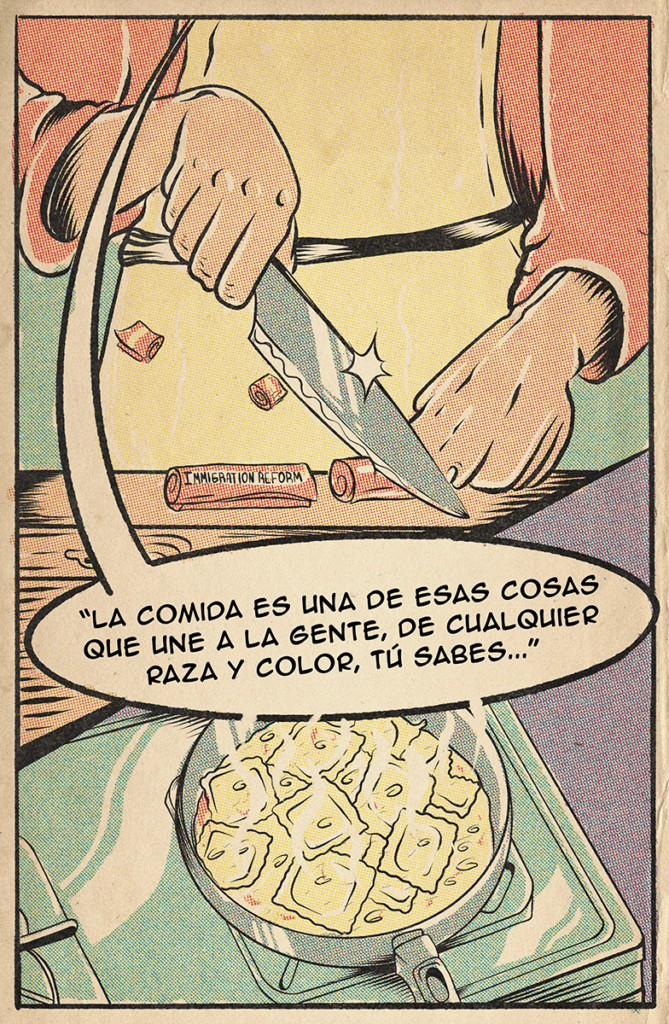

La comida es una de esas cosas que une a la gente de cualquier raza o color, ¿sabes? Todo el mundo se lleva bien cuando hay comida. Así que empecé a trabajar en lo mío.

Al principio de la pandemia, empecé a vender pedidos de comidas caseras para llevar. Se me ocurrió esa idea porque en los restaurantes, por lo general antes de que comience un turno, todos comparten una comida de estilo familiar. Pensé que era una buena idea ya que de todas maneras ya estaba cocinando comida de ese estilo para mis compañeros de casa.

Estaba cocinando pasta, mole y pollo frito, que eran mis mejores ventas. Mi amiga, Yaritza Guillen, me pidió que preparase una cena para su cumpleaños y por supuesto que acepté.

Hice difusión por medio de Instagram cuando estaba haciendo comidas caceras y la mayoría, si no todas las personas que me compraron, vivían en Pilsen, La Villita u otros vecindarios por aquí.

Ayudó mucho poder confiar en mi comunidad y entender que todo el mundo está pasando por un momento difícil y todos están tratando de hacer lo suyo para salir adelante.

Brian Herrera para Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

Sabía que había gente que no tenía los recursos para pagar por la comida, entonces regalé comida porque ser capaz de dar comida a alguien que lo necesita es algo que mis padres me inculcaron.

La comida está hecha para ser consumida y disfrutada, no solo vendida. Pero todos los que ordenaron mi comida trataron de dejar algo de dinero a cambio. Yari ayudó mucho en conseguir clientes, personas con las cuales normalmente no habría tenido contacto. Ella ha sido de tremenda ayuda en hacer que mi nombre sea reconocido y siempre me alienta a hacer lo que amo. Y mis amigos y mi pareja, definitivamente están ayudando mucho también.

Estimo mucho a Yari ya que me está dando la oportunidad de hacer lo que amo, que es preparar comida para la gente.

Cuando llegué a los Estados Unidos tenía 4 años. Mi familia se mudó a Waukegan, que está como a una hora al norte de Chicago y tiene una población mexicana enorme. Viví allí hasta los 23 años.

Lee mas

Después de mudarme busqué trabajo en la ciudad. Había trabajado en un restaurante en la ciudad donde vivía, pero casi todos los restaurantes en Waukegan son corporativos como Applebee’s y me cansé de vivir en ese ambiente.

Quería vivir más cerca de esta ciudad (Chicago) que está repleta de buena comida. Quería formar parte de este mundo culinario. Me mudé a Humboldt Park por un año y esa experiencia fue bastante entretenida mientras trabajaba en una pizzería. Luego me mudé a Pilsen y he estado aquí durante los últimos cuatro años.

Vivir en Pilsen realmente me abrió la mente por sus actividades comunitarias y su forma diferente de pensar. Estaba trabajando en The Bristol como cocinero donde hacíamos cosas como cortes enteros de cerdo.

Aprendí mucho de los chefs Chris Pandel y Abbie Sweeny en los dos años que trabajé allí y definitivamente le agradezco por enseñarme. Ella luego se fue a otro restaurante, The Willow Room, que se encuentra en Lincoln Park al otro lado de la calle de Alinea. Me fui con ella y fui su sous chef (segundo en comando en la cocina) durante un año. Trabajaba entre 80 y 100 horas a la semana, pero necesitaba hacerlo.

Brian Herrera para Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

Pero mientras trabajaba en The Willow Room tuve un accidente automovilístico y debido a las presiones que tenía fuera del trabajo, no podía soportar algunas cosas.

Yo estaba literalmente desecho y no era justo para mis compañeros de trabajo o ni para la chef Abbie Sweeny, así que tomé la decisión de irme del restaurante.

Más tarde empecé a trabajar en Dusek’s en Pilsen, que es donde estaba trabajando cuando la pandemia golpeó y perdí mi trabajo debido a los recortes de personal. Para ayudar a pagar las cuentas estoy trabajando en Lao Peng You, un buen lugar que hace bollos rellenos (dumplings), dos días a la semana.

Postulé a todos los subsidios y subvenciones que pude. Necesito el apoyo, ciertamente. Postulé a la Asociación Nacional de Restaurantes una vez al principio, después al Proyecto de Educación Culinaria de Illinois y lo conseguí. Luego el propio Dusek’s a través de GoFundMe hizo dos rondas de recaudación de dinero. Definitivamente estaba solicitando ayuda, porque la necesitaba y porque no podía estar desempleado. Es decir, tengo dinero ahorrado y todo, pero no sabía cuánto tiempo iba a durar la pandemia.

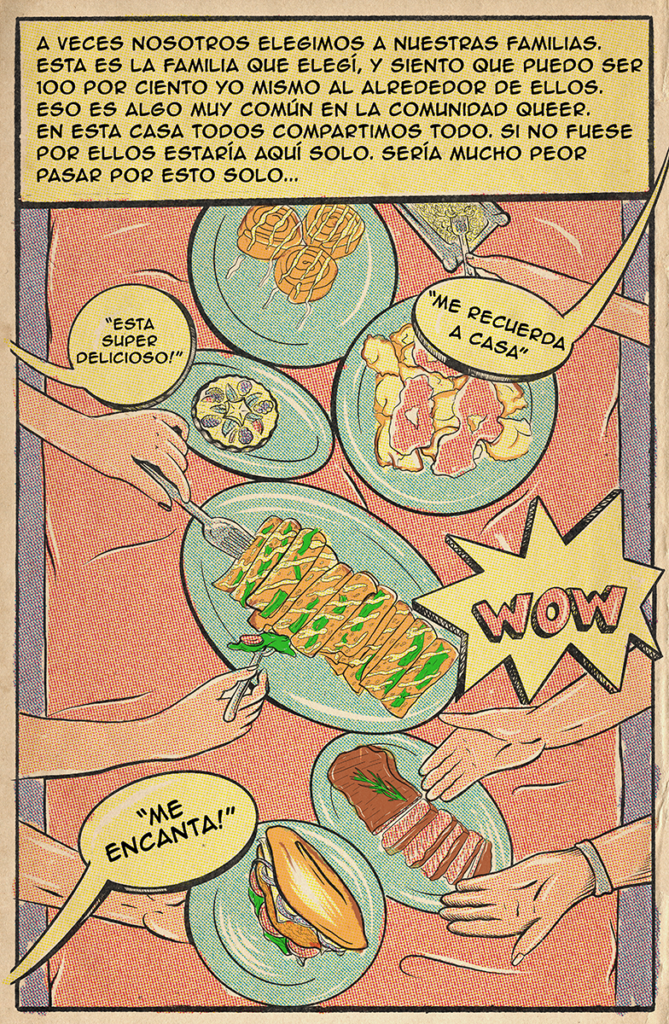

Siendo gay e indocumentado de una familia mexicana muy anticuada… aún no he revelado mi orientación sexual por completo a mis padres. Mis hermanas lo saben y todos aquí en la ciudad lo saben. No trato de esconderme aquí. Esta es la familia que elegí y puedo ser 100 por ciento yo mismo cuando estoy alrededor de ellos.

Brian Herrera para Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local

Eso es algo muy común en la comunidad queer — tener una familia que te crio, pero también tener una familia que uno elige, que te apoyará y nunca te juzgará. Creo que es muy importante tener gente que te cuide y que siempre esté allí incluso en los tiempos más oscuros.

Ser queer e indocumentado hace la vida más difícil. Es difícil ser yo mismo y tener éxito en este mundo a mi manera.

Siento que ser indocumentado es una de esas cosas donde hay ciertas adversidades que nos suceden todo el tiempo. Y aunque es difícil, siempre encontramos la manera de tener éxito y ser lo que queremos ser.

En el futuro me encantaría tener mi propio restaurante o un camión de comida donde pueda hacer mi comida. Quiero mostrarle al mundo que esto es lo que puedo hacer. Esto es lo que puedo ofrecer. Sé que lanzar un restaurante es muy caro y no siempre se tiene éxito. Pero quiero tener un lugar donde pueda hacer feliz a la gente ofreciéndoles mi comida.

Este artículo, publicado originalmente en inglés por Borderless Magazine, está traducido por Marcela Cartagena gracias al proyecto “Traduciendo las noticias de Chicago”, del Instituto de Noticias Sin Fines de Lucro (INN).

Este artículo forma parte de la serie “Resiliencia que inspira”, de Brian Herrera, becario de CatchLight Local. El proyecto ilustra historias de éxitos, desafíos y resiliencia durante la crisis de salud pública de COVID-19 compartida por miembros de la comunidad de inmigrantes indocumentados en Chicago, Illinois.

Esta historia fue producida en asociación con CatchLight Local y el Instituto de Noticias Sin Fines de Lucro (INN) y es parte de nuestra serie Mi barrio me respalda, una serie bilingüe que tendrá un mes de duración reportada por, para y con latinxs de Chicago.