Efraín Soriano para Borderless Magazine

Efraín Soriano para Borderless MagazineMientras los nuevos residentes desentierran décadas de contaminación, algunos vecinos esperan con ilusión la construcción de un parque público en la antigua fábrica de torio.

Durante años, Ata Rehman ha mirado por la puerta de su casa y se ha preguntado cuándo terminarían por fin las obras en las hectáreas de campos vallados cerca de su casa en los suburbios de West Chicago.

Desde que se mudó al otro lado de la calle en 2016, Rehman ha visto rachas de actividad: cuadrillas que iban y venían con maquinaria pesada, seguidas de largos periodos en los que el vasto terreno quedaba abandonado.

"El trabajo es muy lento", afirma Rehman, que emigró de Pakistán en 2010.

¿Quiere recibir historias como ésta en su bandeja de entrada todas las semanas?

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito.

A pesar del trabajo continuo, sabe muy poco de lo que ha estado ocurriendo a unos 15 metros de su porche. Antes de que un reportero y un fotógrafo de Borderless llamaran a su puerta a principios de noviembre, Rehman desconocía que los campos albergaron en su día la mayor instalación de extracción de torio radiactivo y tierras raras del mundo, así como el plan de limpieza del lugar, situado a unos 50 kilómetros al oeste de Chicago.

Tras décadas de esfuerzos de rehabilitación, la limpieza final de las aguas subterráneas de la propiedad de 43 acres está en marcha y se prevé que finalice en 2026. Está previsto construir un parque público en sustitución de la antigua fábrica con el objetivo de dejar atrás la legado tóxico que ha asolado durante mucho tiempo el barrio de mayoría latina.

En la actualidad, camiones volquete, excavadoras y bulldozers están creando 9.000 yardas cúbicas de terraplén, el equivalente a unas tres piscinas olímpicas, alrededor de una celda de tratamiento de suelos prevista. Los trabajos actuales forman parte de la fase final de limpieza de los contaminantes radiactivos y de otro tipo del emplazamiento. Un permiso municipal de obras en el límite de la propiedad describe la "excavación y retirada de tablestacas", pero el pequeño cartel -que los transeúntes pasan fácilmente por alto- no revela la historia del emplazamiento.

En la puerta de su casa, Rehman desearía saber qué está pasando. "Deberían poner una gran pancarta o un cartel que describiera el trabajo que están haciendo, el plan", dijo Rehman señalando hacia la verja.

La limpieza, estancada desde hace tiempo, entra en su fase final

Durante décadas, los residentes de West Chicago expresaron su preocupación por la liberación de material tóxico por parte de la fábrica, pero no se tuvo en cuenta hasta que se adoptaron medidas de protección medioambiental a principios de la década de 1970. El antiguo propietario y el gobierno han tardado más de 30 años en limpiar los residuos radiactivos, mientras que muchos residentes han sufrido las consecuencias. se sintió abandonado en la oscuridad.

La Agencia de Gestión de Emergencias de Illinois (IEMA) supervisa la fase final de limpieza de las aguas subterráneas. Espera entregar la totalidad de la propiedad a la ciudad de West Chicago en otoño de 2026. En septiembre, el ayuntamiento de West Chicago aprobó un plan definitivo para construir el Parque Comunitario de West Chicago en el solar de la antigua fábrica.

La Instalación de Tierras Raras, conocida por los lugareños como la fábrica Kerr-McGee, funcionó entre 1932 y 1973. Al principio producía lámparas incandescentes y más tarde suministró materiales para el desarrollo de la bomba atómica del gobierno federal. Su vertido no regulado de subproductos radiactivos en el lugar y en los barrios circundantes ha dejado un legado de preocupaciones sanitarias y desconfianza.

A principios de la década de 1990, cuatro zonas del oeste de Chicago, que incluían 676 viviendas, fueron incluidas en la Lista de Prioridades Nacionales del Superfondo de la Agencia de Protección del Medio Ambiente. Desde entonces se han limpiado conforme a las normas de la agencia y se han retirado de la lista o están en proceso de hacerlo.

La limpieza del emplazamiento de la fábrica comenzó en 1994 tras una larga batalla entre Kerr-McGee Corporation, propietaria de la fábrica y que planeaba almacenar las pilas de residuos radiactivos in situ, y los residentes de la ciudad, que se movilizaron con éxito para que los residuos se enviaran a una instalación de eliminación en Utah.

Tras la quiebra de Tronox, la empresa derivada de Kerr-McGee, en 2009, la limpieza restante recayó en IEMA, que utilizó los 1.436 millones de euros restantes del acuerdo de quiebra y los fondos federales del Título 10 depositados en un fideicomiso. El pasado mes de diciembre, el representante de los EE.UU. Sean Casten consiguió $2 millones más de fondos para la limpieza como parte de un proyecto de ley de gasto federal de $1,7 billones.

Sang Thuai se mudó al barrio en febrero de 2022 con sus tres hijos pequeños. Pensó que todas las obras del solar se destinaban a construir otra fábrica. Un vecino le dijo que dejara de cultivar las espinacas de agua, la mostaza y los chiles que ella y su familia disfrutan como parte de su cocina birmana, pero ella desestimó los problemas de contaminación como algo del pasado.

"No sabía nada del parque", dijo Thuai. "No sabíamos nada cuando nos mudamos aquí".

La rehabilitación del suelo finalizó en 2015, con lo que los niveles subterráneos de radio y uranio, dos contaminantes radiactivos, se ajustaron a las normas de limpieza. "De donde estaba en la década de 1980 a donde está ahora, el sitio está a cientos de kilómetros de distancia en las condiciones", dijo Kelly Horn, Jefe de la Subdivisión de Servicios de Protección Radiológica de IEMA. "Mientras nadie utilice las aguas subterráneas en las zonas preocupantes", añadió Horn, "no hay riesgo para la salud humana".

Las ordenanzas municipales y del condado impiden a los residentes locales utilizar pozos en las zonas contaminadas por las actividades de la fábrica. Horn añadió que "no existe conectividad" entre el suministro de agua de la ciudad de West Chicago y los acuíferos poco profundos contaminados situados bajo el emplazamiento. La mayor parte del suministro de la ciudad procede de acuíferos profundos, dijo Horn, y los suministros de acuíferos poco profundos de la ciudad se encuentran a más de una milla de distancia del emplazamiento y "en una vía de flujo de aguas subterráneas diferente". Según Horn, lo más lejos que se extiende la contaminación de las aguas subterráneas es 700 pies más allá del perímetro del emplazamiento.

Desde 2015, la consultora de ingeniería medioambiental de IEMA, Weston Solutions, investiga las mejores formas de reducir la contaminación de las aguas subterráneas. Durante sus operaciones, la fábrica Kerr-McGee vertió residuos líquidos en estanques sin revestimiento alrededor del emplazamiento. Unos 20 contaminantes, entre ellos uranio y fluoruro, siguen superando las normas de protección de las aguas subterráneas. Las tablestacas añadidas durante la limpieza del suelo para proteger a los trabajadores que excavaban hasta 70 pies de profundidad han mantenido estancadas las aguas subterráneas, haciendo que los contaminantes se concentren a medida que el agua de lluvia disuelve la contaminación residual en el suelo.

Esta limpieza final implica el bombeo y tratamiento de las aguas subterráneas, la extracción del uranio y otros contaminantes del suelo y la retirada de las tablestacas.

Alrededor de 10% de las aguas subterráneas situadas bajo el emplazamiento se bombearán, tratarán y verterán a través de una tubería de impulsión al río DuPage. Weston terminó la primera parte del tratamiento de las aguas subterráneas en octubre y tiene previsto terminar la segunda después del tratamiento del suelo.

El tratamiento del suelo, cuyo inicio está previsto para mediados de 2024, consiste en trasladar cargas de material previamente limpiado, que cumplía las normas de limpieza y se rellenó en el emplazamiento, a un estanque de doble revestimiento para someterlo a una limpieza adicional con una solución de lixiviado. Esta solución extraerá el uranio restante y pasará por una serie de evaporadores térmicos y secadores de lodos hasta que queden sólidos, que finalmente se enviarán a una instalación de eliminación en Utah.

Por último, a principios de 2026, se retirarán las tablestacas para permitir que el flujo natural de las aguas subterráneas diluya los contaminantes restantes, según el IEMA.

Weston informa de que las actividades de limpieza, que incluyen las emisiones procedentes de la evaporación de la solución lixiviada, el polvo del traslado de camiones cargados de tierra, posibles accidentes como incendios y el vertido de agua tratada al río DuPage, no deberían perjudicar a los residentes ni al medio ambiente si se siguen todas las medidas de seguridad.

IEMA controla semestralmente los contaminantes de las aguas subterráneas a través de una serie de pozos dentro y fuera de la propiedad. Seis estaciones de control alrededor de la fábrica también miden las partículas en el aire, el gas radón y torón, y la radiación gamma directa semanal o trimestralmente. Hasta ahora, las mediciones realizadas en estas estaciones no han superado los límites de dosis al público. La agencia está estudiando un plan mínimo quinquenal de control de las aguas subterráneas y la necesidad de realizar más controles ambientales una vez concluida la limpieza actual.

Según el Informe de análisis medioambiental de fase VI publicado por el IEMA el año pasado, estos tratamientos tienen por objeto reducir los niveles de contaminantes "al nivel más bajo razonablemente posible" y permitir la excavación y el traslado del suelo sin perjudicar a la población. Tras la limpieza en tres fases, se prevé que las aguas subterráneas alcancen los niveles de protección mediante dilución natural en un plazo de 375 años.

El plan del parque público del oeste de Chicago pretende olvidar la historia tóxica del lugar

Refugio Arias lleva observando el progreso de la antigua fábrica desde que su familia se mudó al barrio hace 20 años. Conocía la contaminación de la fábrica y está deseando que la propiedad se convierta por fin en un parque que los residentes puedan utilizar. "No ha pasado gran cosa", dijo Arias, "hasta ahora".

Aunque el Estado sigue limpiando el lugar, algunos vecinos siguen preocupados por la seguridad de los trabajadores y la seguridad general del lugar una vez finalizada la limpieza.

Ata Rehman se pregunta si los trabajadores siguen los protocolos de seguridad radiológica. "No veo que lleven máscaras", afirma. Rehman afirma que ha hablado con varios trabajadores, y todos le han dicho: "No sabemos qué está pasando. Sólo trabajamos aquí".

Según el IEMA, los trabajos actuales se están realizando en suelos ya rehabilitados con niveles de contaminación iguales o inferiores a los límites reglamentarios. Weston deberá cumplir la normativa estatal sobre dosis de radiación ocupacional durante las operaciones de lixiviación del suelo y eliminación del uranio.

La activista local Julieta Alcantar-García quiere ver una prueba final de radiación antes de que se construya el parque. "Es muy importante para nuestra comunidad, sobre todo si pensamos en niños jugando encima de estos terrenos, saber que esa zona es segura para construir", afirmó. A Alcantar-García también le gustaría ver un monumento en memoria de los residentes que han sufrido los efectos de la radiación de la fábrica sobre su salud, quizá en forma de plantación de árboles para las víctimas.

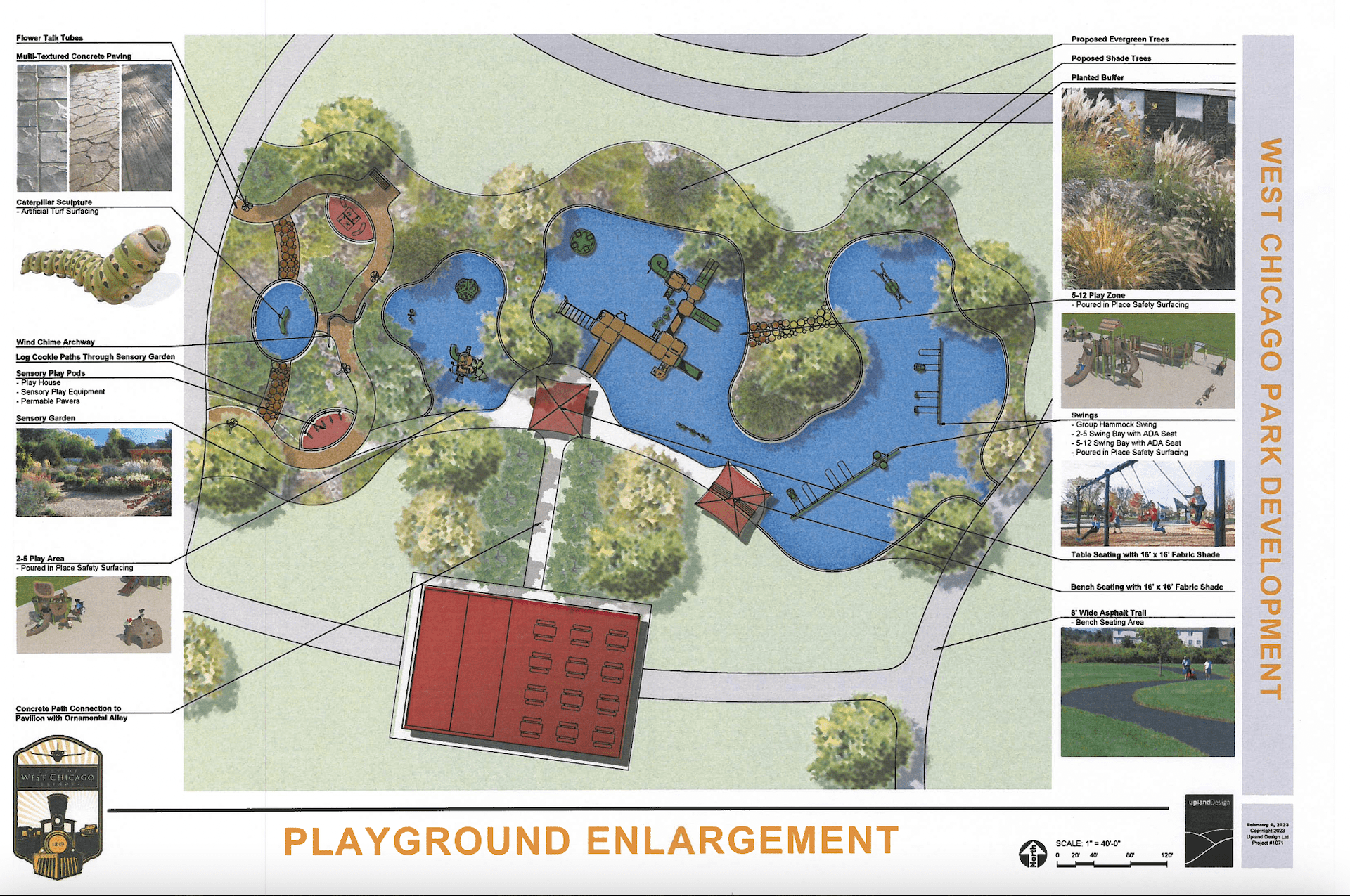

En el departamento de Desarrollo Comunitario de la ciudad, el director Tom Debareiner ha dirigido el proceso de planificación del parque, que ha incluido foros comunitarios. El plan aprobado, con un coste estimado de $15 millones, incluye plantaciones autóctonas, canchas de pickleball, tenis y baloncesto, campos de fútbol, un parque infantil, senderos, un jardín sensorial y mesas de picnic, entre otras características.

La ciudad no lo ha presupuestado y espera obtener financiación estatal y de otro tipo para introducir progresivamente diversos elementos del parque. Debareiner dijo que las plantaciones naturales en la zona norte del recinto comenzarán en unos dos años. "Definitivamente está en nuestra mente", añadió Debareiner, "proporcionar algún tipo de reconocimiento a las personas que trabajaron tan duro antes limpiando el sitio".

Al otro lado de la calle, Andrew Marsh y su pareja estaban en el porche mirando por encima de la valla de alambre forrada de tela la maquinaria que movía la tierra alrededor de la antigua fábrica. Está deseando pasear a su perro por el parque. "Parece que están haciendo su trabajo, así que no me puedo quejar", dijo Marsh, y añadió: "Espero que lo hayan conseguido todo".

Da poder a las voces de los inmigrantes

Nuestro trabajo es posible gracias a las donaciones de personas como usted. Apoye la información de alta calidad haciendo una donación deducible de impuestos hoy mismo.