Ilustración cortesía de Organized Communities Against Deportation

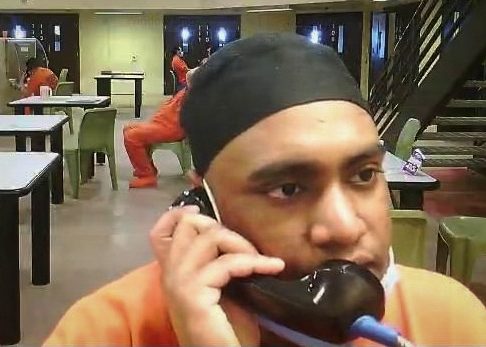

Ilustración cortesía de Organized Communities Against DeportationAl-Amin Porosh ha ayudado a otros detenidos a desenvolverse en un opaco sistema de detención de inmigrantes y ha creado una comunidad entre rejas.

Cuando Illinois decidió cerrar sus centros de detención de inmigrantes a principios de este año, los grupos de defensa y los abogados se vieron obligados a luchar para encontrar a clientes que habían sido trasladados repentinamente a cárceles y centros de detención privados de todo el país.

En la cárcel del condado de McHenry, en los suburbios de Chicago, Al-Amin Porosh, un inmigrante de Bangladesh de 25 años, resultó ser un salvavidas para obtener información.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

"No hubo ninguna comunicación [del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas]", dijo Karina Solano, coordinadora de defensa contra la deportación en la Oficina de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas. Comunidades organizadas contra las deportaciones. "Fue fundamental en la organización. Para nosotros era muy importante poder conectar con la gente de dentro y sus familias de fuera para coordinarnos."

Sus esfuerzos ponen de relieve los numerosos retos a los que se enfrentan las personas atrapadas en el mayor sistema de detención de inmigrantes del mundo, una red en gran medida opaca de cárceles locales y prisiones privadas repartidas por todo Estados Unidos. Cerca de 23.000 inmigrantes detenidos por el ICE. Casi 70% de estos inmigrantes no tienen antecedentes penales -ni siquiera una infracción de tráfico- e incluyen a muchas personas que buscan seguridad en Estados Unidos como Porosh.

Los inmigrantes detenidos juntos no suelen hablar el mismo idioma y son trasladados con frecuencia de un centro de detención a otro, lo que dificulta enormemente la coordinación de recursos y la protesta por las peligrosas condiciones de detención, como temperaturas bajo cero y condiciones sanitarias deficientes.

Pero a pesar de la incertidumbre sobre su propia solicitud de asilo y la amenaza de deportación, sus compañeros de prisión afirman que Porosh ha creado una comunidad entre rejas.

"Es alguien a quien acudirías cuando estás atascado", dice Amadi, un inmigrante de 28 años de África Occidental que pidió utilizar un seudónimo en este reportaje debido a su caso de inmigración pendiente.

Amadi dijo que debía su reciente liberación del centro de detención de inmigrantes a Porosh, que le presentó a los abogados que le ayudaron a salir en libertad.

"Imagínese si no le hubiera conocido", dijo Amadi.

Un organizador comprometido

Porosh llegó a Estados Unidos en marzo de 2021 y lleva detenido desde entonces. Abandonó Bangladesh en 2015 y, tras pasar años en Malasia, decidió venir a Estados Unidos. Cuando llegó al aeropuerto internacional O'Hare de Chicago, fue detenido por el ICE y enviado inmediatamente a la cárcel del condado de McHenry, en Woodstock, a 100 km al noroeste de Chicago.

Porosh y su abogada, Marwa Jumma, se negaron a comentar por qué huyó de Bangladesh, aludiendo a su caso de asilo y a una orden de expulsión.

En una petición en línea para su liberación, OCAD describe Porosh como "organizador comprometido y trabajador de servicios", que a los 16 años fue "perseguido, amenazado y dañado físicamente como consecuencia de su activismo político" en un movimiento liderado por estudiantes en Bangladesh para promover la democracia.

"Vine a este país para salvar mi vida, para tener una vida mejor y así poder ayudar a la gente", dijo Porosh durante una llamada telefónica con Borderless.

Después de que un juez de inmigración denegara la solicitud de asilo de Porosh el pasado mes de junio, se procedió a su expulsión. Su abogado presentó un recurso ante el Tribunal de Apelaciones del Séptimo Circuito de Estados Unidos, que aún está pendiente.

Su experiencia en busca de asilo no es inusual.

A mediados de julio, 22.886 inmigrantes fueron detenidos por el ICE y el Servicio de Aduanas y Protección de Fronteras de EE.UU. en todo el país y otros 296.250 inmigrantes estaban siendo controlados a través de los programas de Alternativas a la Detención del ICE. En el año fiscal 2021, se denegaron hasta 63% de casos de asilo, según TRACuna organización no partidista de recopilación de datos de la Universidad de Syracuse. Eso se compara con una tasa de denegación máxima de 71% durante la Administración Trump.

Muchos inmigrantes también se enfrentan a largas esperas en los centros de detención. Según el Servicios de Ciudadanía e Inmigración de EE.UU.La decisión sobre una solicitud de asilo debe tomarse en un plazo de 180 días a partir de su presentación. Pero un análisis de TRAC de casos de asilo presentados ante los tribunales desde 2001 concluyó que más de 667.000 solicitantes de asilo siguen esperando una vista sobre su caso. El tiempo de espera actual para la resolución de un caso de asilo es de casi cuatro años y medio.

Hasta la fecha, Porosh ha pasado más de 16 meses recluido como inmigrante en cárceles de cuatro estados distintos, tras habérsele denegado cuatro veces la libertad vigilada. Jumma dijo que las decisiones se dictaron sin explicación alguna por parte del tribunal.

El tiempo que Porosh ha pasado detenido a la espera de asilo en Estados Unidos es similar a la duración de una condena de cárcel por un delito grave, dijo Jumma.

"No tiene antecedentes penales. No es una amenaza para la comunidad", dijo Jumma. "Es una persona de carácter moral, una persona honesta que ayuda a los demás".

Crear una red de apoyo

Alex Ortiz, inmigrante mexicano de 27 años, pasó tres meses con Porosh en la cárcel del condado de McHenry. Sus celdas no estaban lejos la una de la otra y ambos se hicieron amigos.

Recordó una noche en la que a él, a Porosh y a un detenido anciano les pidieron que limpiaran sus secciones del bloque. Porosh se apresuró a terminar de limpiar su sección para poder limpiar a tiempo la zona del anciano.

"No se limita a decir que quiere ayudar", dijo Ortiz. "Está ayudando de verdad, y eso me parece extraordinario".

Después de que Illinois cambiara su legislación para que las cárceles de los condados no pudieran retener a inmigrantes para el ICE, Porosh se puso en contacto con otros inmigrantes y los puso en contacto con organizadores como Solano, de OCAD, que podían pasar información a las familias de los inmigrantes y proporcionar recursos como asistencia jurídica. Cuando se recluía a personas en régimen de aislamiento, alertaba a los defensores para que pudieran seguir la pista de aquellos de los que no tenían noticias.

Porosh suele ponerse en contacto con ellos para hablar de los detenidos que necesitan ayuda, dijo Solano. Incluso cuando estuvo a punto de ser deportada el pasado junio, Porosh la llamó para que ayudara a un detenido guatemalteco, cuyo caso iba a ser revisado, a encontrar alojamiento para después de su puesta en libertad.

También creó una "red de apoyo en el interior", según la OCAD, lo que llevó a algunos detenidos a implicarse más y hacerse oír más sobre las condiciones de su detención. Esto incluyó una carta colectiva* protesta por las condiciones de la cárcel del condado de McHenry, firmada por 30 personas el pasado invierno.

"Todos hemos estado detenidos durante demasiado tiempo sin que se nos permitiera ver a un juez, sin el debido proceso", según la carta, en la que se citaban cuestiones como temperaturas "gélidas" en las celdas y mala calidad de la comida y de la atención médica. "Están jugando a la ruleta rusa con las vidas de los detenidos del ICE".

La carta también protestaba por la práctica de poner en cuarentena a los detenidos sanos en sus celdas durante la pandemia, aislamiento que tuvo repercusiones negativas en la salud mental y física de las personas, según la carta.

"Esto demuestra el poder de conectar con los demás y trabajar juntos, incluso cuando se está en régimen de aislamiento absoluto", afirmó Solano.

Porosh, que trabajaba en la cocina de la cárcel de McHenry, envió a todos sus escasos ingresos a sus padres y a su hermana pequeña en Bangladesh. Su caso de asilo y la situación de su familia pesaban mucho sobre él. Para animarle, Ortiz y otros detenidos contribuían todos los viernes a comprarle una de sus comidas favoritas: pizza de queso.

"Esos fueron los momentos en los que realmente pudimos verle reír y estar un poco más relajado", dijo Ortiz.

Si ayudo a la gente, no es por mí

Aún no está claro si Porosh podrá permanecer en Estados Unidos.

El pasado mes de junio, fue sometido a un procedimiento de deportación y trasladado de la cárcel de McHenry al centro de detención de Prairieland, en Alvarado (Texas). La representante del distrito 9 de Illinois, Jan Schakowsky, intervino entonces para congelar su deportación, a la espera de una decisión del tribunal. Con el cierre de los centros de detención de Illinois, Porosh fue devuelto a la cárcel del condado de Kay, en Newkirk (Oklahoma), donde cumplió 25 años el mes pasado.

"No hice nada por mi cumpleaños, porque estoy en la cárcel", dijo Porosh. "Eso ya no me importa. Sólo necesito una buena vida".

Porosh dijo que vino a Estados Unidos por amenazas contra su vida y para ayudar a su familia en su país. Cuando lo pongan en libertad, quiere encontrar un trabajo que le permita devolver algo a la comunidad.

"Algunos piensan que si ayudo, quizá obtenga beneficios. Yo sólo ayudo porque leo el Corán", dijo Porosh. "Sé que un día estaré muerto, así que si ayudo a la gente, no es por mí".

Antes de ser trasladado al sur, Ortiz y Porosh solían pasar el rato en la zona común de su cárcel de Illinois para charlar sobre su vida, su familia y sus sueños.

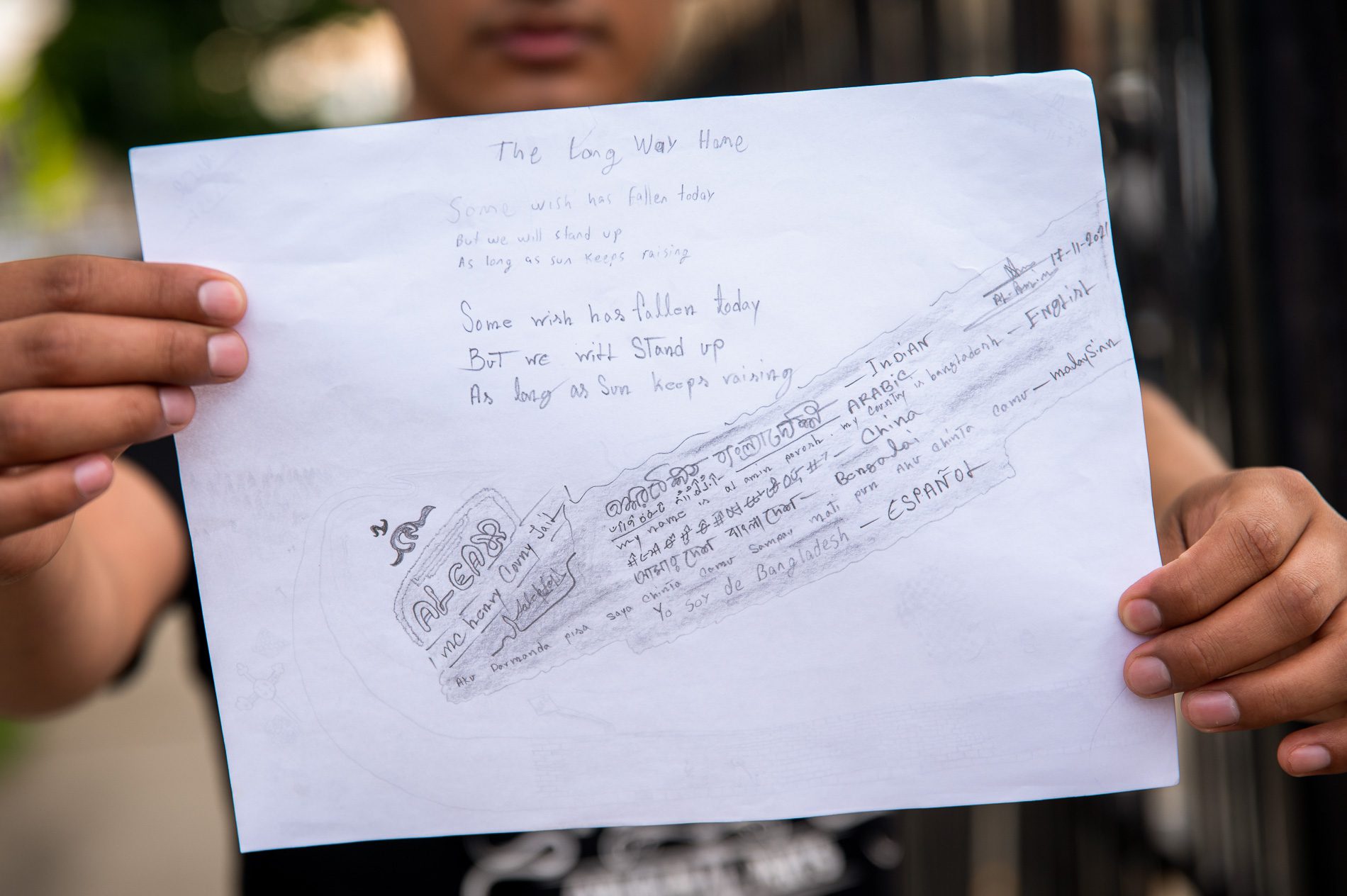

Ortiz, que fue puesto en libertad en enero, recuerda una noche de noviembre en la que él y Porosh se sentaron a hacer un dibujo juntos. Todavía conserva el dibujo, y a menudo lo mira y piensa en su amigo.

La imagen muestra a un hombre sentado en una cornisa bajo un sol deslumbrante, con vistas a los campos de cultivo que recuerdan a Ortiz su propia casa en el México rural. En el reverso del papel escribieron un poema.

"Algún deseo ha caído hoy", reza el poema. "Pero nos levantaremos / Mientras el sol siga saliendo".

*Este es un extracto de una carta de tres páginas firmada por 30 inmigrantes detenidos en la cárcel del condado de McHenry. Hemos omitido partes de la carta para proteger la identidad de los detenidos cuyos casos de inmigración pueden verse afectados negativamente.