Fotografía de Irina Zadov

Fotografía de Irina ZadovLos artistas y educadores de Chicago que están detrás del programa "small is all" hablan de lo que les motiva en la ciudad.

En agosto de 2020, las artistas Irina Zadov, Abena Motaboli y Peregrine Bermas se reunieron en un jardín comunitario del barrio Englewood de Chicago. Los artistas docentes del Distrito de Parques de Chicago y sus alumnos habían pasado apuros durante la pandemia, con el cierre de muchos espacios artísticos y el traslado de las clases a Internet, y los artistas se habían reunido en Earl's Garden Mae's Kitchen para devolver la ayuda como parte del programa Teaching Artist Mutual Aid.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

Mientras trabajaban entre remolachas y berzas, hablaron de las relaciones de los artistas con la tierra y la vida que les rodea.

"Muchas veces, en el mundo del arte se presta atención a obras de gran tamaño y destructivas para el medio ambiente, como el movimiento land art, dominado por hombres blancos y cis", afirma Zadov, especialista en programas del distrito de parques. "Pero el trabajo de escardar y cubrir con mantillo y prestar atención a los seres vivos que nos rodean es tan importante como las obras de arte más monumentales".

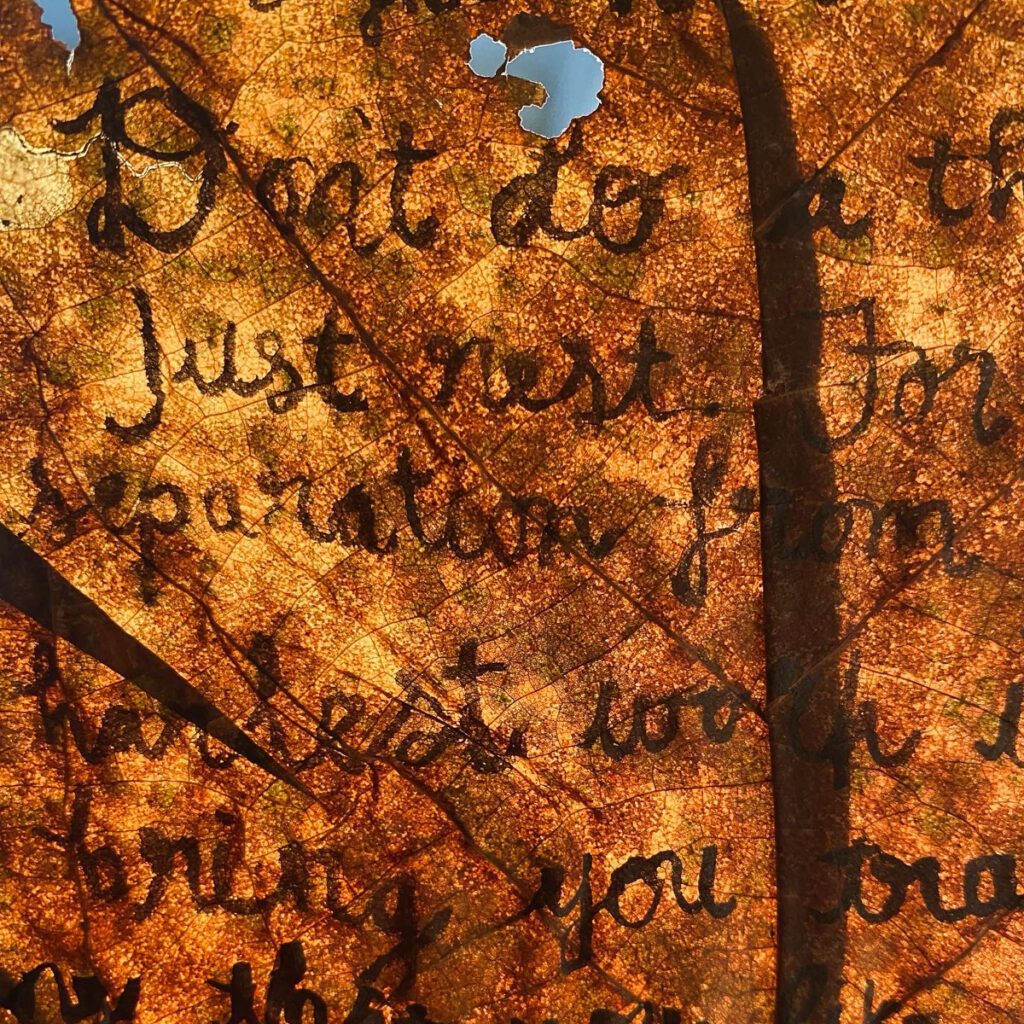

El trío, junto con la también artista Gabriela Garay, decidió hacer de esa idea la base de su próxima clase, "Pequeño es todo". En este programa de ocho semanas que fusiona el arte con la justicia racial y medioambiental, los alumnos conectan con la naturaleza a través de la observación de aves y las excursiones, y flexionan sus músculos creativos. Basándose en la obra de la escritora de la liberación negra adrienne maree brown y la ecologista potawatomi Robin Wall Kimmerer, el curso pretende "transformar el daño causado a los pueblos indígenas, las plantas, los animales y las relaciones sagradas por el genocidio, la colonización y la degradación cultural y medioambiental, restableciendo la relación entre esta tierra y sus pueblos indígenas".

El curso toma su nombre de una frase del libro "Emergent Strategy" de Brown: "Lo pequeño es bueno, lo pequeño es todo (Lo grande es un reflejo de lo pequeño)". En cada clase, 20 jóvenes de 10 a 15 años eligen un "pequeño" -una planta, animal o ser vivo- para observarlo y reflexionar sobre él durante tres meses. El ejercicio pretende restablecer su relación con la tierra, las plantas y los animales en una época de fatiga del Zoom y sobrecarga de las redes sociales.

Ahora, los artistas comparten su plan de estudios "pequeño es todo" con educadores y trabajadores juveniles de todo el país. Antes de su Presentación del plan de estudios el juevesLos artistas explicaron a Borderless Magazine qué es lo que les motiva en Chicago, una cuestión que se analiza en el curso a través de debates sobre migración, colonización y justicia racial y medioambiental.

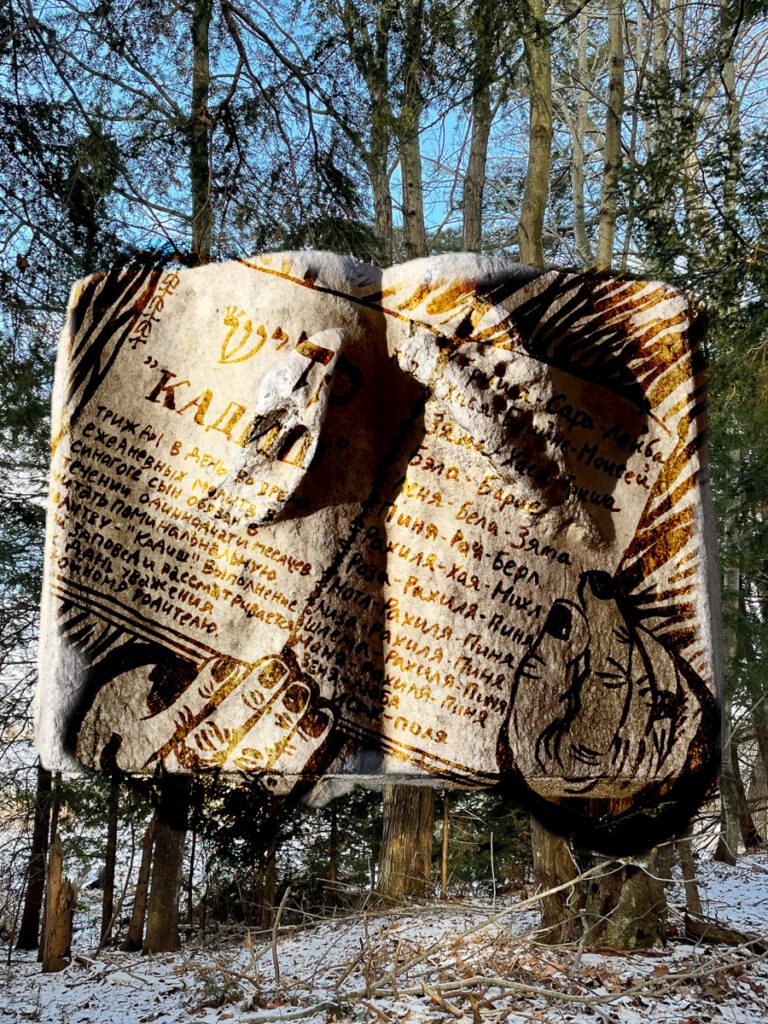

Irina Zadov

Lo que me motiva es mi conexión con la tierra. En mi país natal, Bielorrusia, los bosques eran mi espacio sagrado de pertenencia. Abedules, pinos, setas y ardillas fueron algunos de mis primeros y mejores amigos. Aprender sobre las plantas autóctonas del Medio Oeste ha sido muy enraizante. Es un placer descubrir que algunos de mis antepasados del otro lado del océano también son autóctonos de los Grandes Lagos, como el cedro, el abedul, el enebro, la espadaña, el musgo, la milenrama y el diente de león.

También sé que ambas tierras guardan recuerdos de traumas, genocidios y desplazamientos forzosos. Cuando visito Belarús, camino sobre las tumbas sin nombre de mis antepasados judíos, cuyos nombres e historias sigo aprendiendo. Cuando camino por Illinois, honro a la Confederación de los Tres Fuegos: Ojibwe, Odawa y Potawatomi; y también a los pueblos Myaamia, Inoka, Ho-Chunk y Menominee. Me siento honrado de ser huésped de esta tierra. Como inmigrante y colono, me comprometo a vivir mis valores de solidaridad, reciprocidad y reparación.

También me siento profundamente arraigada a mis relaciones con las comunidades de artistas y organizadores de Chicago. Recuerdos de pintar murales en viaductos, comisariar actuaciones pop-up en casas y callejones, arrancar malas hierbas y compartir comidas en jardines comunitarios y apoyar el liderazgo de los organizadores BIPOC en las calles... Encuentro un sentido de pertenencia en estos momentos de acción colectiva, cocreación y relaciones arraigadas en la liberación y la sanación.

Peregrino Bermas

A riesgo de sonar cursi, lo que me une a Chicago es el amor. He necesitado casi 30 años en Chicago para reconstruir y apreciar mi historia aquí. He estado reflexionando sobre ello porque se acerca mi cumpleaños. Mis padres emigraron aquí en los años ochenta y noventa procedentes de lo que se conoce como las Islas Filipinas. Tenían una casa en West Lakeview, donde yo vivía con un par de abuelos y cruzaba la calle para ir a la guardería de otro par de abuelos. Mis padres tenían una tienda de ladrillos, lo que nunca deja de darme vueltas ante el dios del cambio. Los veranos eran dorados y los inviernos duros, a diferencia de los inviernos de ahora.

Después de que nos desplazaran de ese hogar, recuerdo constantes movimientos que desestabilizaron mi sentido de comunidad y conexión con el lugar, aunque nunca nos mudáramos lejos. Solía avergonzarme demasiado expresar mis propias historias de Chicago, que son recuerdos fragmentados, no lineales y poéticos que ahora he llegado a apreciar. Comprometerme a sanar mi historia aquí significó redefinir muchos de estos términos para mí (comunidad, conexión, hogar).

Afortunadamente, reunirse en bandada en un lugar acaba por reunir a tu gente, y yo he reunido a un hermoso grupo (¡de todas las especies!) en mi corazón y en mi conciencia. Nos reunimos hasta que aprendemos a cuidarnos y protegernos unos a otros. Las formas en que nuestras historias se entretejen unas con otras y el eco ancestral de nuestra demostrada fortaleza colectiva me despiertan la curiosidad y me inspiran a ser valiente.

La conexión que siento con Chicago está en esta llamada y respuesta, y también en la memoria viva y el dolor del cambio que se mantiene palpable en un lugar. Me conmovió saber que algunos de mis amigos crecieron en el bloque donde mi padre almorzó por primera vez después de emigrar aquí, y me conmovió sentarme junto a un álamo y saber que probablemente tiene menos de 300 años debido a la tala generalizada, y me conmovió escuchar a una joven en un taller decir que su abuela hace una olla de medicina de vapor de la misma manera que mi abuela y mi madre me enseñaron. Chicago es la tierra que me hizo crecer, y espero corresponder al regalo.

Gabriela Garay

Como hija de inmigrantes, me siento muy especial al poder decir que soy de aquí, de la tierra conocida como Illinois. Todos los lugares en los que he vivido siguen existiendo y están a unas cuatro horas de distancia unos de otros, y esto es algo que sé que mucha gente no puede decir. Soy el primero de mis hermanos que nació en esta tierra y me siento honrado de haber vivido toda mi vida aquí, en estos paisajes rurales, urbanos y suburbanos y rodeado de muchas de las mismas plantas y animales. Pero es ahora, como adulto, cuando aprendo sus nombres y los reconozco allá donde voy. A medida que ha crecido mi relación con esta tierra, también lo ha hecho mi deseo de honrarla y protegerla.

Vivo en Chicago desde hace unos cuatro años y medio, y lo que realmente me arraiga aquí es lo pequeño. Especialmente durante la pandemia, a menudo he sentido que mi relación con la tierra y su vida no humana era la más segura, la menos complicada y la más presente. Cada temporada he podido notar algo diferente en la tierra y el paisaje de esta ciudad, que a menudo me ha parecido viejo y nuevo al mismo tiempo, aunque en parte sea un nuevo recuerdo. En esta larga temporada de pandemia, esto me ha parecido tan enraizante y reconfortante. Las relaciones han cambiado y crecido en cada estación, pero actualmente es poder saludar al lago, a las varas de oro, a los robles, a los siluros, a los arándanos y a las ardillas lo que me ha dado una sensación de hogar y de lugar. Ver estas plantas también me ha recordado los momentos y lugares en los que han aparecido en mi vida, incluso cuando no era tan consciente de su presencia. Ahora me doy cuenta de que siempre han estado ahí.

Abena Motaboli

Me intriga la idea de hogar. Mi familia y yo emigramos de Lesotho, en el sur de África, a Estados Unidos en 2012; mi madre es de ascendencia ghanesa y togolesa y mi padre de ascendencia basotho y ndebele.

Cuando pienso ahora en mi lugar en Chicago, me acuerdo de lo conectada que me sentí al crecer en un país montañoso donde había naturaleza y amor por el medio ambiente por todas partes. Cuando nos mudamos a Illinois, me encontré buscando algo con lo que conectar a través de mi práctica artística, haciendo objetos con materiales encontrados, tierra, té, café, la tierra y objetos efímeros para conectar con algo que siempre ha estado a mi alrededor. Últimamente he estado pensando en el suelo y en la conexión con la tierra como una forma de conectarme dondequiera que vaya: el suelo fue lo primero que tocaron mis pies, está conmigo ahora y estará allí cuando vuelva a la tierra. El suelo literal de Chicago me enraíza aquí.

En los últimos años he estado aprendiendo más sobre las prácticas indígenas en la tierra y los pueblos indígenas de este país. Siento una fuerte conexión con la importancia de las relaciones recíprocas con la tierra y todos sus seres vivos, ya que así es como han vivido mis antepasados durante siglos. Recuerdo las prácticas de mis parientes en una pequeña aldea y veo el amor por este lugar que llamamos hogar, nuestra conexión con el agua, la tierra, los animales y las plantas.

Otra cosa que llevo conmigo es la palabra "Ubuntu", que en Sudáfrica se traduce como cierta unión con un enorme énfasis en la interdependencia, la comunidad y el entendimiento mutuo: nadie se queda atrás. Chicago es un lugar donde durante los últimos siete años he encontrado mi Ubuntu en el trabajo que hago, y eso es eternamente enraizante.

Los artistas de "small is all" organizan un intercambio de planes de estudios el jueves 2 de diciembre de 17.00 a 18.30 horas CST. Regístrese aquí.

El próximo curso de "pequeño es todo", organizado por el Distrito de Parques de Chicago, empezará en febrero. Inscríbase en esta clase virtual aquí.