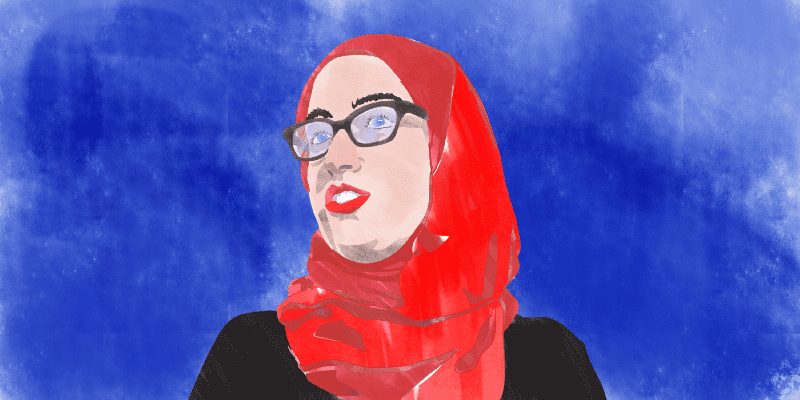

Hadia Zarzour es consejera clínica profesional y cofundadora de Syrian Community Network, una organización sin ánimo de lucro decidida a ayudar a los refugiados sirios reasentados a construir una nueva vida en Estados Unidos.

Hadia Zarzour es consejera clínica profesional licenciada y cofundadora de la Syrian Community Networkuna organización sin ánimo de lucro decidida a ayudar a los refugiados sirios reasentados a construir una nueva vida en Estados Unidos. Hadia enseñó Introducción a la Psicología a estudiantes universitarios en Damasco. También es cofundadora de Insan, una organización sin ánimo de lucro fundada en 2012 con el propósito de prestar apoyo psicológico a niños y adultos sirios en Turquía, Jordania y Líbano.

Hadia habló de la vida, la terapia y los recuerdos con Borderless el 20 de febrero, poco antes de que el presidente Trump emitiera una nueva prohibición de viajar para los sirios. Compartió sus experiencias como terapeuta de refugiados y cómo encontró su segundo hogar en Chicago.

Me encanta cuando te encuentras con gente inesperadamente en Chicago. Te hace sentir que tienes raíces aquí. En Damasco siempre me encontraba con mis alumnos y amigos por toda la ciudad. Típico de un profesor, ¿verdad? Siria siempre fue mi hogar, pero luego Chicago se convirtió inesperadamente en mi hogar también.

Cuando pierdes tus raíces, sientes que una parte de la historia de lo que eres ha desaparecido. Lo veo en las familias de refugiados de aquí y en mí mismo. Creo que por eso sigo aferrada a Siria. Damasco es una gran ciudad, pero al mismo tiempo en mi corazón se sentía pequeña. Damasco tenía algo íntimo y real.

Llegué a Chicago en 2009 para cursar un máster. Era la primera becaria Fulbright en Siria especializada en psicología del asesoramiento y mi plan era terminar el programa y volver para abrir un centro de asesoramiento en la Universidad Árabe Internacional de Damasco. Me faltaban pocos meses para terminar cuando empezó la revolución en 2011.

Para ser sincera, en Siria hay una especie de estigma contra los estudios de psicología y la carrera de orientación psicológica. Siempre abordé la terapia desde el deseo de ayudar a la gente con sus problemas. Tal vez fuera una forma idealista de ver el mundo como estudiante, pero siempre sentí que podía soportar y llevar el peso de ayudar a la gente a superar sus traumas. Los sirios en general no hablan de sentimientos individuales. Si pasas tiempo con sirios, te darás cuenta de que decimos mucho "nosotros". Creo que esto es indicativo de cómo pensamos en el grupo, no en el individuo. Al final, todo es cuestión de comunidad.

La terapia consiste en expresarse y eso significa hablar, y a menudo hablar de sentimientos se traduce en debilidad. Parecer débil es duro. He trabajado con otras comunidades de refugiados en Chicago durante cuatro años, pero ahora estoy centrada en trabajar con refugiados sirios reasentados. Me reúno con estas familias de refugiados donde se encuentran, tanto emocional como físicamente. A veces hacemos terapia de grupo para hablar de experiencias compartidas, pero la mayor parte de mi terapia es a través de la gestión de casos con Syrian Community Network. Para los refugiados que desconfían de la terapia, se desarrollan vías alternativas para compartir sentimientos. Las preguntas sobre la depresión toman forma en conversaciones sobre patrones de sueño, dolor de espalda, dolores de cabeza, quizá recuerdos. Es una conversación en la que nunca se entra directamente. Se trata de un lenguaje tácito y de lo que está oculto.

También nos centramos en satisfacer sus necesidades básicas. La seguridad en los barrios donde las agencias de reasentamiento colocan a las familias es un problema. Imaginemos que una madre sobrevivió al Ataque químico en Ghouta en 2013, perdiendo un marido y un hijo, y luego está viviendo en un barrio con tiroteos. Sobrevivió a un ataque químico con cuatro hijos, pero aquí está siendo re-traumatizada por la violencia armada de Chicago.

La violencia doméstica, los intentos de suicidio, a veces simplemente el estrés de trasladarse a Estados Unidos y empezar una nueva vida son también problemas. Creo que el momento más duro para mí como terapeuta fue estar al lado de una madre siria cuando perdió a su bebé en el hospital justo después de nacer. Es encontrar el equilibrio entre superar el trauma y ayudarles a echar raíces en un nuevo hogar.

Hoy empiezo a preocuparme por mis propias raíces en Siria. Siento que poco a poco mis vínculos con el país van desapareciendo. Toda mi vida en Siria, a pesar de la presión a lo largo de nuestras vidas, se sentía como si estuviera conduciendo a este momento de libertad. Estar fuera durante el comienzo de la revolución me hizo sentir que, de alguna extraña manera, me perdía los escasos momentos de libertad que, de niña, descubría en los libros de contrabando que mi padre escondía detrás de otros libros en la biblioteca de nuestra casa. Viví mi vida esperando este momento de cambio, y ahora siento que eso se ha ido. Eché de menos el honor de estar en las calles de Damasco con otros valientes manifestantes pacíficos.

Pero luego pienso: ¿qué es Siria? Se me parte el corazón cuando pienso en ello. Al final, es sólo gente. Es un símbolo. Es un hogar. Pero ahora, Chicago también es un hogar. Cuando camino por la calle, siento que pertenezco a Chicago, pero es una de dos vidas. Es un poco como la vida después de la muerte. Siento que he pasado de mi vida siria a mi vida estadounidense, y que todo ha desaparecido, excepto mi familia. Pero cuando hablas de lo que pasa en Siria, o de los recuerdos de tu vida allí, casi estoy conectando mis dos mundos.