La falta de personal médico bilingüe deja a los hispanohablantes a la deriva, y con dolor.

Este artículo se ha publicado en colaboración con Proyecto de periodismo penitenciariouna organización nacional sin ánimo de lucro que forma en periodismo a escritores encarcelados y publica sus trabajos. Suscríbase al boletín de PJP boletínsíguelos en Instagram o conéctese con ellos en LinkedIn.

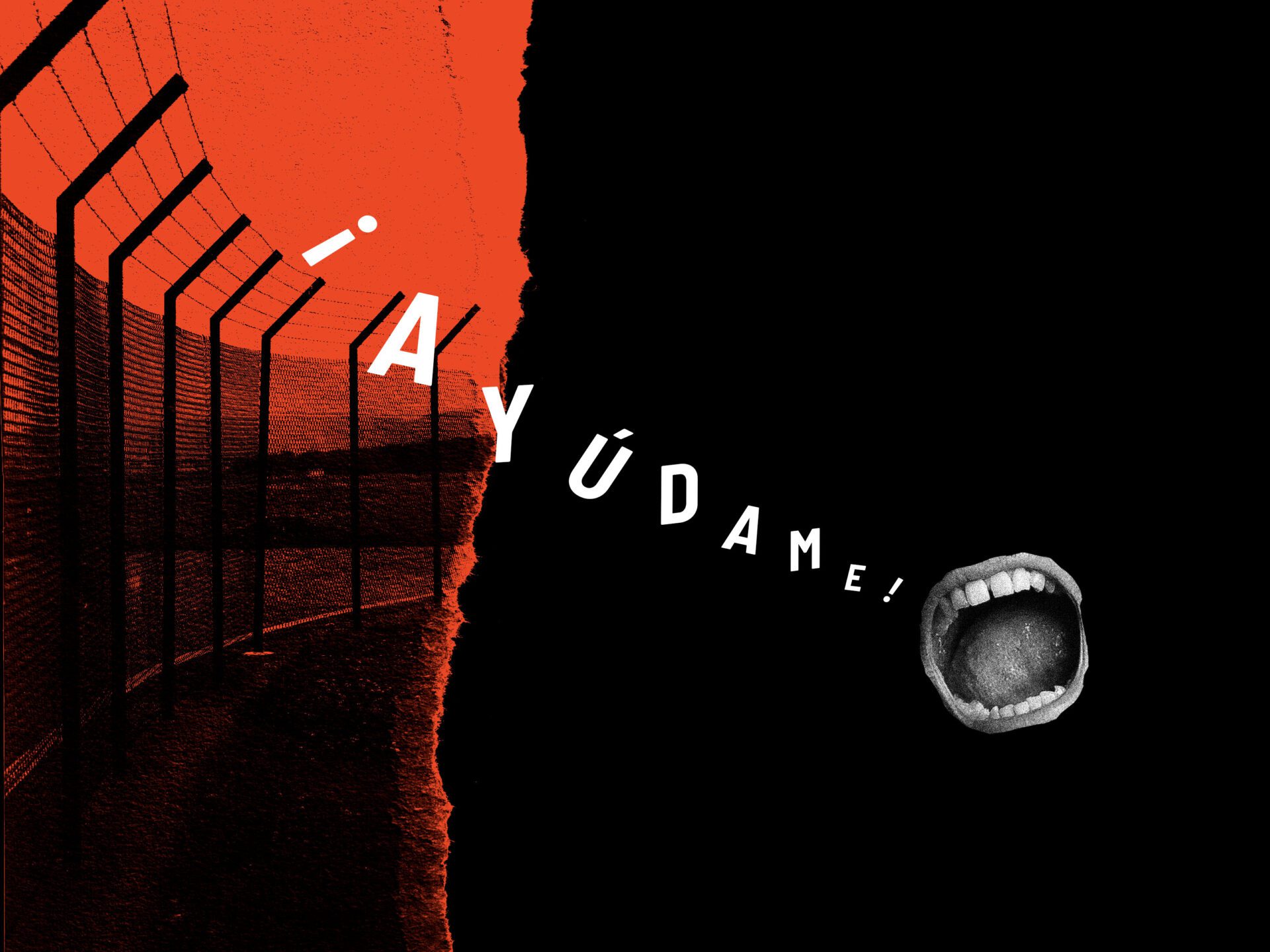

"¡Neto! ¡Ayúdame a escribir una nota para la enfermería!" grita el señor José a través del agujero alambrado de la puerta de mi celda, que apesta a óxido cuando te acercas demasiado.

Me pide que le escriba una nota de solicitud para visitar la enfermería. Claro que sí puedo, respondo. "Claro que sí puedo."

La asistencia de traducción es crucial para las personas encarceladas que hablan inglés como segundo idioma o no lo hablan en absoluto. Muchos hispanohablantes dentro de mi prisión de Illinois creen que sus identidades les impiden recibir atención médica adecuada.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

Hay que hacer algo al respecto. Como mexicano-estadounidense bilingüe de primera generación, ofrezco asistencia lingüística a todos los hispanohablantes que necesiten ayuda. La comunicación en materia de atención sanitaria es un gran problema. A menudo, la gente necesita ayuda para escribir hojas de solicitudes médicas y describir sus síntomas. Este es el primer paso para cualquiera que intente acceder a la atención sanitaria en prisión.

Pero se requieren soluciones más sistémicas. Contratar médicos y enfermeras bilingües es una opción; otra es utilizar la telemedicina para acceder a un grupo más amplio de proveedores médicos bilingües. A corto plazo, la prisión podría recurrir más a las herramientas de traducción de inteligencia artificial u organizar eventos ocasionales en los que traductores confidenciales acudan a la prisión para ayudar a los hispanohablantes que buscan atención médica.

La barrera lingüística entre la población reclusa y el personal provoca una especie de insensibilización. Los reclusos hispanohablantes evitan hablar de su dolor, lo que lleva a la creencia errónea de que no hay dolor del que hablar. Esa narrativa debe cambiar.

Consideremos el señor José, que emigró de México a EE.UU. a los 20 años y ahora tiene 68 años. Como gran parte de la población reclusa que envejece, padece varias dolencias y dice que no recibe una atención sanitaria adecuada para un hombre de su edad. La ciática y la acidez crónica le mantienen despierto por la noche, dice. Y hace años se cayó de la litera de arriba y se lesionó la cadera. Como muchos inmigrantes encarcelados, José sólo habla español.

Más información

En la cárcel, el señor José necesita un permiso para caminar despacio para desplazarse entre los edificios sin ser multado. Hay que solicitar este permiso, confiando en que la burocracia penitenciaria reconozca y responda a los desafíos físicos articulados en la solicitud.

El proceso de solicitud, que pide a los pacientes que describan su estado de salud a médicos y guardias mayoritariamente monolingües, es engorroso. Requiere un nivel de inglés que los inmigrantes como José simplemente no poseen.

La lucha por transmitir los síntomas y entender los diagnósticos puede ser peligrosa. También es humillante, dicen los hispanohablantes, por lo que les disuade de buscar atención médica. Lo mismo es cierto para los residentes bilingües cuya falta de acceso a la educación les ha dejado incapaces de comunicar adecuadamente sus necesidades por escrito.

Y así, muchos esperan, con la esperanza de que la tos se calme o el dolor de cabeza se disipe, porque hablar o escribir es sentirse ridiculizado o, peor aún, ignorado.

Por supuesto, en lugar de mejorar por sí sola, la enfermedad suele agravarse, especialmente en las personas mayores e inmunodeprimidas. El malestar físico dificulta incluso movimientos sencillos como caminar o sentarse. Al final, se requiere una interacción aún más compleja desde el punto de vista médico -y lingüístico- con el personal sanitario.

Víctor es un guatemalteco de mediana edad que me deleita con repeticiones verbales de la Copa América de fútbol. Hace poco me contó que los guardias no le abrieron la puerta de la celda para su dosis diaria de insulina, algo que, según él, ha ocurrido antes. Víctor tiene diabetes de tipo 1, una enfermedad autoinmune de por vida que requiere una dosis diaria de insulina para regular la glucosa en sangre. Aunque no debe consumir alimentos sin la dosis de insulina, al final tiene tanta hambre que tiene que comer. Los efectos fisiológicos son inmediatos.

Víctor cree que los guardias saben que es diabético, ya que dice que su nombre aparece en la lista de puertas que hay que desbloquear para la administración de insulina.

Aunque su inglés es limitado y está muy acentuado, lo entiendo. Él interpreta que el hecho de que los guardias no le abran la puerta se debe a su identidad y a su idioma —todos los demás residentes diabéticos de su celda hablan inglés con fluidez. Peor aún, teme que su barrera lingüística le impida recibir la medicación adecuada.

Las personas encarceladas dependen de la burocracia penitenciaria para satisfacer sus necesidades básicas de atención sanitaria. Se espera que aboguemos por nuestra propia atención sanitaria. Pero, como en el caso de Víctor y su dosis de insulina olvidada, quienes carecen de las habilidades lingüísticas o de lectoescritura necesarias para abogar por sí mismos pueden quedar al margen.

Mientras tanto, seguiré ofreciendo mis servicios de traducción a mis compañeros hispanohablantes. Desempeñar este papel me parece tanto un acto de servicio como un acto de resistencia. Por lo que he observado, la discriminación que sufren las personas mayores, los enfermos crónicos, los discapacitados y las personas que no son blancas fuera de los muros de la prisión se agrava para los que están dentro. Frente a esas barreras, tengo el deber de hacer mi parte para ayudar a cerrar la brecha entre quienes prestan asistencia médica y la gente -mi gente- que la necesita. que lo necesitan.