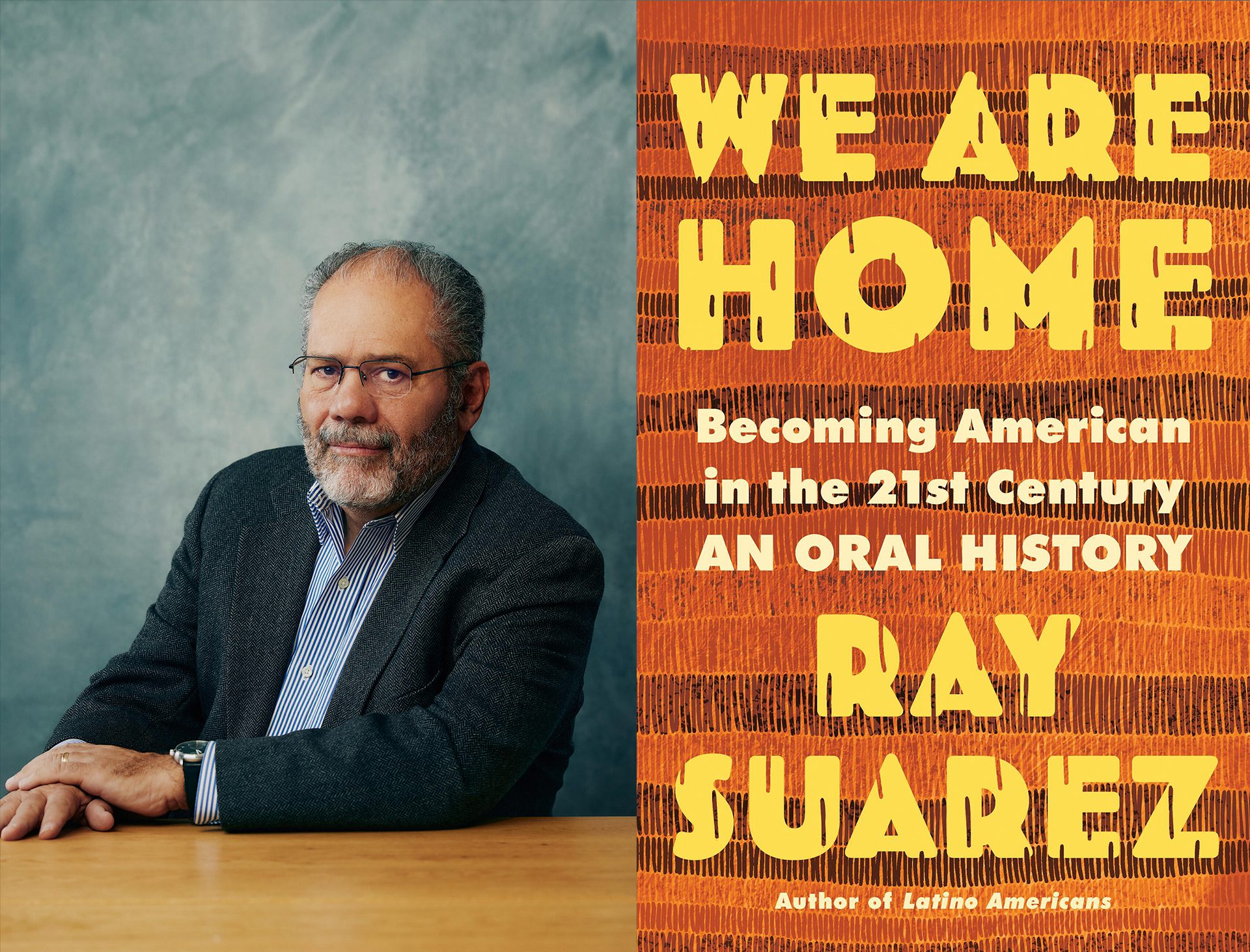

El periodista Ray Suárez examina en su último libro las políticas de inmigración en Estados Unidos al tiempo que relata la vida de los nuevos inmigrantes en todo el país.

El veterano periodista y escritor Ray Suárez recorrió el país para su nuevo libro, hablando con nuevos inmigrantes que crean una nueva vida en Estados Unidos.

En "Estamos en casa", Suárez examina las políticas de inmigración a la vez que relata las vidas de los inmigrantes, que sortean obstáculos sin dejar de resistir la adversidad.

Extraído de WE ARE HOME por Ray Suarez. Copyright © Ray Suarez 2024. Utilizado con permiso de Little, Brown and Company, un sello de Hachette Book Group. Todos los derechos reservados.

Noticias que ponen el poder en el punto de mira y a las comunidades en el centro.

Suscríbase a nuestro boletín gratuito y reciba actualizaciones dos veces por semana.

Interludio

Samir

nacido en Mombasa, Kenia

Yo ya tenía 20 años, y era como si te hubieras ganado el billete dorado, ¿no? Tenía familia y primos aquí, así que algo sabía, como que no era algo del tipo "las calles estaban pavimentadas con oro". Tendrás que trabajar.

Mis padres nacieron en Kenia y Tanzania durante la época colonial, la época colonial británica, así que éramos, supongo, la segunda o tercera generación, y éramos originarios de Yemen. Así que cuando crecí ya era un inmigrante de nacimiento. La forma en que hablaban de Yemen, y especialmente sus padres, mis abuelos, era siempre como si un día fuéramos a volver. Así que te sentías keniata por crianza, pero a veces, ya sabes, al ir a la escuela te dicen que eres árabe. Vuelve a casa, ¿no?". Averiguar dónde estaba su hogar se convertiría en el rompecabezas que pasaría las siguientes décadas de su vida resolviendo.

Los colonos y comerciantes de la península arábiga llevan siglos desplazándose hacia el sur por la costa africana del océano Índico. Hay asentamientos y ciudades árabes desde el Mar Rojo hasta lo que hoy es Mozambique. El swahili, lengua franca de gran parte de África Oriental, está plagado de palabras y estructuras lingüísticas árabes.

Samir, ahora en la cuarentena, delgado, compacto, de piel morena, pelo castaño y ojos marrones, se sentiría como en casa paseando por innumerables calles del Sur Global. Desde su más tierna infancia navegó por múltiples culturas y nacionalidades. Tras una primera infancia en la ciudad costera keniana de Mombasa, se trasladó a Arabia Saudí cuando su padre consiguió un trabajo allí, y luego regresó a Kenia a los once años. La reincorporación, recuerda, no fue tan fácil. Su swahili se había acentuado tras años en el extranjero. Su árabe estaba moldeado por el dialecto particular de Arabia Saudí. "Recuerdo que se burlaban de mí, incluso los otros niños árabes. Recuerdo que intenté encajar de nuevo".

Cuando Samir intentaba volver a Kenia, su vida dio un giro inesperado. Sus padres se divorciaron. Su padre regresó a Arabia Saudí. Una tía, hermana de su madre, se había trasladado a Estados Unidos y había inscrito a la madre de Samir y a sus hijos en el sistema de lotería para el llamado visado de diversidad. A diferencia de otras partes cada vez más exigentes de los estatutos de inmigración estadounidenses, el visado de diversidad, creado por una ley de inmigración de 1990, es literalmente un juego de azar. Cada año, el gobierno estadounidense concede cincuenta mil visados a solicitantes seleccionados al azar de países con bajos índices de inmigración a Estados Unidos. La mayoría de los solicitantes, y la mayoría de los ganadores, proceden de África.

Millones de personas solicitan visados de diversidad cada año. Como ocurre con las loterías estatales, las probabilidades de ganar un premio que te cambie la vida son minúsculas.

La madre de Samir ganó. Recogió a sus hijos y se fue a Maryland a vivir con su hermana.

Samir sabía que tendría que trabajar duro. Y que no sería fácil.

"Cuando llegué aquí, aunque hablaba inglés y tenía una red de contactos y apoyo, me sorprendió mucho la nostalgia que sentía por Kenia. Allí sabía cómo moverme. Era popular. Ahora, fui a los suburbios de Columbia, Maryland, y realmente me sentí como en un desierto, muy sola. No había cafés. La gente ni siquiera sabía el nombre del vecino y cosas así".

Incluso cuando le tocó la lotería, se rompió el corazón y tuvo que tomar una difícil decisión. "Una cosa que le rompió el corazón a mi madre al venir aquí fue que mi hermano tenía más de veintiún años. Estaba en la universidad en Kenia. Mi hermano mayor. Soy el segundo de cinco hermanos. Y le dijeron que con los visados de diversidad sólo podía trasladarse con cuatro de sus cinco hijos. Al mayor había que expedirle una tarjeta verde aparte.

"Lloraba mucho porque era la segunda vez que dejaba a mi hermano mayor. Cuando nos mudamos a Arabia Saudí, mi padre había dejado a mi hermano mayor porque ya había empezado el colegio y estaba aprendiendo inglés. Ninguno de nosotros (hermanos pequeños) había empezado la escuela cuando nos mudamos. Ahora, todos estos años después, mi madre decía: 'Voy a hacer esto otra vez. Lo dejo por segunda vez'. Nunca se había perdonado lo de la primera vez, así que estaba destrozada. Entonces mi tía dijo, 'Oh, sólo va a tomar un año para obtener su tarjeta verde.' Así que pensamos. En realidad tardó quince años".

Samir tranquilizó a su madre diciéndole que había hecho lo correcto. Acababa de terminar el instituto. Un hermano menor estaba en el instituto y una hermana en la escuela secundaria. La familia se hacinó en una casa adosada en Columbia, Maryland, con la tía de Samir y su familia, hasta que los cinco pudieron alquilar una casa propia en las cercanías. Debió de darles vueltas la cabeza. Mombasa es una pintoresca ciudad portuaria que mezcla influencias árabes, africanas y coloniales británicas. La cálida brisa del océano Índico difunde los aromas de los mercados de especias y los puestos de comida al aire libre. A lo largo del día, la llamada a la oración del muecín resuena por las antiguas calles.

A siete husos horarios de distancia, Columbia, Maryland, era una urbanización planificada, una ciudad modelo destinada a ser pionera en un nuevo tipo de urbanismo de densidad media para las áreas metropolitanas de Estados Unidos. El promotor James Rouse quería demostrar un tipo de urbanización que combatiera la expansión descontrolada y, al mismo tiempo, dejara espacio para el empleo, la vivienda, el ocio y la asistencia médica, todo ello a poca distancia. Es difícil

pensar en dos lugares menos parecidos que Mombasa y Colombia. Escuchar a Samir

contarlo, se lo tomó todo con calma.

"No fue difícil asimilarlo rápidamente. Conseguí trabajo. Trabajé en McDonald's y en Wawa. Uno de mis primeros trabajos en Wawa fue en la charcutería. Hablaba con acento keniano. La mayoría de la gente cuando se muda aquí, piensa que los americanos hablan rápido. Casi no oyes ni la mitad de las palabras. ¿Qué dicen? Pero todo lo que oyes es wa, wa, wa, ¿verdad?

"¡No conocía todos los quesos diferentes! Y la gente era muy exigente. Quieren atún con pan de centeno, con esto, pero no con aquello. Pensé: 'Dios mío, ¿cuántos quesos tiene esta gente? Estas son las cosas que se me quedan grabadas. Recuerdo, ya sabes, el tipo me está mirando. Es algo así como una configuración de Subway. Él me está viendo hacer su sándwich y yo estoy en pánico. "¿Y qué diablos es el condimento?"

Samir, que llevaba pocas semanas en Estados Unidos, tenía dos empleos a tiempo completo en dos empresas muy estadounidenses: Wawa, la cadena de tiendas de conveniencia del Atlántico medio, y McDonald's. Quería matricularse en la universidad, pero dudaba. Quería matricularse en la universidad, pero dudaba, incluso mientras trabajaba esas horas extenuantes. Su tía se ofreció a prestarle el dinero para matricularse. "Pero me sentía muy inquieto. Y tenía miedo de despilfarrar el dinero. Que no iba a ser un buen estudiante, porque la universidad estaba justo enfrente. Y esa no era la universidad como yo la imaginaba. Yo quería ir a la universidad de Animal House. Pero esta era una universidad comunitaria. Iba a vivir en casa. Iba en autobús. No era divertido".

Estábamos sentados en una cafetería de estilo cubano en los suburbios del Distrito de Columbia, en Maryland, mientras me contaba su historia, llena de suave autocrítica y frecuentes referencias a la cultura pop estadounidense... televisión, cine, música. Sin embargo, cuando la familia acababa de deshacer las maletas en su nuevo hogar, el joven keniano hizo algo audaz.

Se alistó en el ejército de Estados Unidos.

"Llegué a este país en mayo. El primero de agosto ya me había alistado en el ejército. Estaba viendo reposiciones de Seinfeld o algo así por la noche, y ponían el anuncio de reclutamiento 'Sé todo lo que puedas ser'. ¡Y gana dinero para la universidad! Le dije a mi tía que me llevara al centro de reclutamiento.

"Unos años antes había visto A Few Good Men, y me gustó mucho ese uniforme. Ya sabes, me imaginaba como Tom Cruise, así que entré en la sección de los Marines, era un puesto de reclutamiento conjunto, y creo que no entraba mucha gente porque se sorprendían un poco al verme.

"Les dije: '¿Puedo entrar? Y me dijeron: '¡Ah, sí, claro! Adelante". Y entonces les hablé de los trabajos que tenían. Les dije que quería dinero para la universidad. Pero pienso en el pasado, y un par de cosas me estaban impulsando. Estábamos cómodos, de clase media, en Kenia. Teníamos ayuda doméstica. Teníamos criadas. Teníamos cosas, y venir aquí y ver a mi madre tomar el autobús para ir al centro comercial, Columbia Mall, realmente me mató. Ella trabajaba en JCPenney. Vendía zapatos. Es como, 'Oh Dios mío, ella va a buscar zapatos para la gente.' Para mí, se sentía por debajo de ella. Pero yo sabía que necesitábamos el dinero.

"Pensé: '¿Qué estoy haciendo? ¿No puedo ir a la universidad? Y en ese momento había querido ir a la facultad de Derecho. Pensé: 'Dios mío, ¿tengo que ir cuatro años a la universidad y luego tres a la facultad de Derecho, y todo ese tiempo mi madre va a medir los pies de la gente y a tocarles los pies?'. Me mataba.

"No se lo dije, porque no quería que se sintiera mal. Y a ella no pareció importarle. Estaba contenta. Siempre había sido ama de casa y esas cosas, y aquí aprendió a conducir. Tomaba clases de informática. Lo disfrutaba.

"Una de las razones por las que entré en el ejército fue esta: Yo estaba como, está bien, voy a ayudar a proporcionar. Estoy matando dos pájaros de un tiro. Ganaré dinero para la escuela. Saldré de los suburbios. Y ayudaré a mi madre".