Ashlee Rezin Garcia/Sun-Times

Ashlee Rezin Garcia/Sun-Times Los activistas están abordando las bajas tasas de vacunación en las comunidades latinas, pero se enfrentan a grandes obstáculos, desde teorías conspirativas hasta la desconfianza en el gobierno.

Arriba: La Dra. Marina Del Rios de University of Illinois Health, la primera persona en vacunarse contra el COVID-19 en Chicago, recibe su 2ª y última dosis en el Norwegian American Hospital el martes. Ashlee Rezin Garcia/Sun-Times

Cuando este invierno Jorge Mújica vio un vídeo en YouTube en el que se afirmaba que las vacunas COVID-19 contienen células de fetos abortados, no se lo podía creer. Se sintió aún más perturbado al día siguiente, cuando vio otro vídeo que traducía la desinformación al español.

En los últimos meses, el veterano organizador con Levántate Chicagouna organización de defensa de los derechos de los trabajadores, ha escuchado una amplia gama de objeciones a las vacunas COVID-19 por parte de la población inmigrante hispanohablante. Sus argumentos van desde la preocupación legítima por los efectos secundarios hasta teorías conspirativas.

Frustrado por la desinformación rampante y la falta de material educativo en español sobre la seguridad de las vacunas, Mújica tomó cartas en el asunto. En diciembre, desde su apartamento del barrio de Pilsen, en Chicago, se puso en directo en Facebook para explicar en español conceptos fundamentales como qué es una vacuna y cómo interactúa con el cuerpo humano. Los 80 minutos vídeo ha recibido más de 4.700 visitas.

Jorge Mújica entra en directo en Facebook para explicar en español conceptos fundamentales como qué es una vacuna y cómo interactúa con el cuerpo humano.

"La gente decía que de ninguna manera se vacunarían y que preferirían dimitir de sus puestos de trabajo", dijo Mújica. "Después del vídeo, realmente conseguimos que estas personas dijeran: 'Estaba en contra, pero lo que has dicho tiene sentido, así que me vacunaré'".

Chicago ha entrado en Fase 1B de las vacunas COVID-19que permite a los trabajadores esenciales de primera línea y a los residentes mayores de 65 años recibir sus primeras dosis. Pero la población latina de la ciudad, a pesar de ser uno de los grupos más afectados por la pandemia, está recibiendo las vacunas en tipos mucho más bajos que los residentes blancos.

Aunque activistas como Mújica han tomado la iniciativa de educar a sus comunidades, las ideas erróneas sobre las vacunas y la profunda desconfianza hacia el gobierno siguen disuadiendo a algunos inmigrantes latinos de vacunarse. Los inmigrantes indocumentados se enfrentan a obstáculos adicionales, como la preocupación por la posibilidad de revelar su estatus migratorio a los funcionarios de salud del gobierno y la confusión en cuanto a si son elegibles para una vacuna.

Hasta ahora, los proveedores de servicios sanitarios han administrado más de 190.000 vacunas dosis en Chicago. Según los responsables municipales, no existen datos completos sobre raza y etnia, ya que los socios sanitarios no suelen recoger esta información de los receptores de las vacunas. El Departamento de Salud Pública de Chicago de estimados que sólo el 17% de todas las personas que han recibido una primera dosis son latinas, aunque datos censales muestran que este grupo representa casi el 30% de la población total de la ciudad. Esta brecha es especialmente preocupante si se tiene en cuenta que los residentes latinos presentan las tasas de mortalidad COVID-19 más elevadas entre los habitantes de Chicago: cuatro veces más altas que las de los residentes blancos, una tasa de mortalidad que se sitúa entre las más altas de la ciudad. análisis reciente espectáculos.

A partir del 2 de febrero de 2021, Chicago reporta 45.404 personas completamente vacunadas: 1,6% de la población.

Quién se muere: Quién está vacunado: pic.twitter.com/7i8CcER26v

- ChiVaxBot (@ChiVaxBot) 3 de febrero de 2021

Semanario South Side código abierto Twitter bot, creado por Bea Malsky y Charmaine Runes, visualiza las concentraciones relativas de muertes por COVID-19 y residentes completamente vacunados hasta la fecha. Los códigos postales predominantemente negros y latinos tienen el mayor número de muertes por COVID-19 y, sin embargo, las tasas más bajas de vacunación completa en Chicago. Las cifras se actualizan diariamente.

La disparidad llevó a la alcaldesa Lori Lightfoot a anunciar un nuevo plan la semana pasada para distribuir más dosis a las comunidades minoritarias más necesitadas. Protect Chicago Plus se asociará con organizaciones locales de los barrios del sur y el oeste para desarrollar clínicas de vacunación, equipos de ataque y otras estrategias de distribución.

Uno de los mayores retos de los funcionarios de salud pública será superar la falta de confianza en la vacuna. Según encuestas de la Kaiser Family Foundation, publicado el pasado mes de diciembre, sólo el 26% de los adultos latinos manifestaron que se vacunarían lo antes posible, en comparación con el 40% de los adultos blancos. Aproximadamente seis de cada diez encuestados negros y latinos dijeron que no sabían dónde vacunarse, mientras que sólo la mitad de los adultos blancos dijeron lo mismo. Además, aproximadamente un tercio de los adultos latinos no cree que el proceso de desarrollo de vacunas tenga en cuenta sus necesidades.

Entre estos adultos se encuentran personas como "Roberto", un inmigrante mexicano de 55 años que pidió utilizar un seudónimo por temor a ser perseguido por sus creencias. Roberto vive en Logan Square con su familia y se gana la vida construyendo equipos de procesamiento de alimentos.

Como maquinista, Roberto pasa la mayor parte de su jornada laboral en un espacio aislado. Dice que si su jefe le obliga a vacunarse, dejará el trabajo.

"La vacuna no nos va a ayudar en nada, y no te puedes fiar de ningún medicamento porque no sabes lo que contiene", afirmó Roberto. Añadió que el gobierno está dejando que el coronavirus se desboque para "ponernos en jaque" y controlar a la población.

Roberto es uno de los cientos de miles de seguidores de Shiva Ayyadurai, un influencer indio-estadounidense que utiliza plataformas en línea como YouTube para impulsar conspiraciones del "Estado profundo" y teorías médicas infundadas. Los contenidos en los que aparecen estas teorías conspirativas son compartidos con frecuencia en canales de YouTube en español como GR8 América e Informativo G24, páginas de Facebook y grupos de WhatsApp.

Aunque la hija de Roberto, en edad universitaria, dio positivo en COVID-19 el pasado mes de octubre, Roberto afirma que no cree que él mismo pueda contraer el virus. No lleva mascarilla y dice que no se vacunará.

Las campañas de desinformación en línea y los canales de las redes sociales que se desvían de los puntos de vista científicos están contribuyendo a los altos niveles de indecisión de los inmigrantes latinos sobre las vacunas, pero su desconexión con el gobierno va más allá de unos pocos canales de YouTube, según Sofia Zaman, directora ejecutiva de Alianza "Levantemos el Sueloorganización con sede en Chicago que atiende a trabajadores inmigrantes y con salarios bajos.

El Departamento de Salud Pública de Chicago ofrece un hoja informativa sobre la vacuna en español.

"La gente no quiere inyectarse la llamada 'vacuna Trump'", dijo Zaman. "La administración Trump ha sido increíblemente hostil y realmente ha avivado el fuego de la supremacía blanca en este país. Y por eso ha habido una larga campaña para instigar e infundir miedo."

"Hay muchas noticias falsas", añadió. "Pero al mismo tiempo, la historia de este país y la historia del sector sanitario no tienen un gran historial. Hay mucho daño que tenemos que reconocer que se ha hecho a nuestras comunidades".

Este historial incluye médicos esterilizar a la fuerza a las latinas y otros inmigrantes. Tan reciente como el pasado mes de septiembre, una denuncia reveló que las mujeres detenidas en un centro del Servicio de Inmigración y Control de Aduanas (ICE) en Ocilla, Georgia, fueron presionadas para someterse a procedimientos ginecológicos que incluían histerectomías.

Jim Witte, director del Instituto de Investigación sobre Inmigración de la Universidad George Mason, destacó cómo las preocupaciones específicas de los inmigrantes -entre ellas el miedo a las detenciones y deportaciones- también han exacerbado la indecisión ante las vacunas.

"Existe el temor de que si quieres vacunarte, la gente descubra que no estás aquí con la debida autorización", dijo Witte. "Si en un hogar hay varios estatus de inmigrante, puede que toda la familia se muestre reacia a vacunarse porque no quieren dar su dirección".

Aunque el ICE dijo que no llevaría a cabo redadas en centros sanitarios o cerca de ellos, Witte señaló que décadas de desconfianza, sumadas a la retórica antiinmigrante difundida por el expresidente Donald Trump, se ciernen sobre millones de familias inmigrantes. El pasado mes de marzo, justo un día antes de que el ICE anunciara que "retrasaría las acciones de aplicación de la ley" ante la pandemia, agentes de inmigración equipados con máscaras N95 estaban llevando a cabo operaciones de aplicación de la ley, el Los Angeles Times informó.

El Departamento de Salud Pública de Illinois ha aclarado que todos los residentes, independientemente de su estatus migratorio, pueden recibir las vacunas COVID-19. Pero en otros estados, los mensajes engañosos de los funcionarios han aumentado la ansiedad y la confusión de los inmigrantes. El gobernador de Nebraska, Pete Ricketts, por ejemplo, alegó falsamente que los inmigrantes indocumentados no pueden recibir la vacuna COVID-19.

Para superar los contratiempos, los funcionarios federales, estatales y locales tendrán que replantearse sus estrategias de comunicación. Una solución es recurrir a la ayuda de organizadores locales, como Mújica, que pueden actuar como intermediarios culturales para la población latina.

"Algunas comunidades de inmigrantes dependen realmente de sus organizaciones locales para buscar información cultural y lingüísticamente específica sobre salud, especialmente porque algunas de ellas no tienen una clínica habitual", dijo Randy Capps, Director de Investigación de Programas de EE.UU. del Instituto de Política Migratoria. Sugirió que los funcionarios sanitarios reclutar intérpretes, defensores de la salud y activistas en los barrios latinos trabajar como intermediarios entre los inmigrantes y los proveedores de asistencia sanitaria.

Seguir leyendo

"Soy optimista y creo que los inmigrantes aprovecharán la vacuna si está disponible y accesible en un entorno no amenazador", añadió Capps.

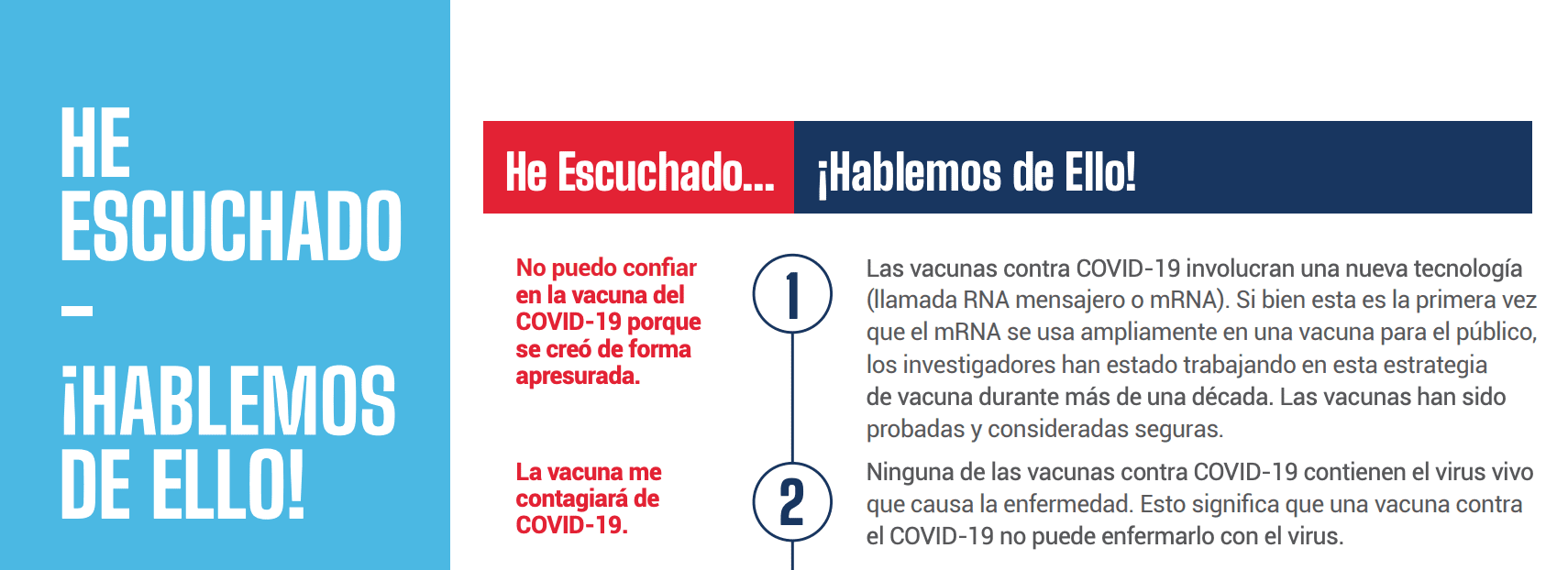

A medida que el estado redobla sus esfuerzos de vacunación, más de 70 organizaciones Latinx, funcionarios electos y expertos en salud se han unido a los Iniciativa COVID-19 para los latinos de Illinoisuna coalición que utiliza campañas bilingües para educar a las comunidades latinas sobre el coronavirus. Mújica, que trabaja con Arise Chicago, participa en la iniciativa, que lleva nueve meses en marcha, desde junio. Al principio, fue difícil conseguir que los funcionarios de salud pública participaran en sus reuniones, dijo, "pero ahora nos toman en serio".

La iniciativa ha publicado una serie de hojas informativas, tanto en inglés como en español, sobre la COVID-19. Según un portavoz de la alianza, este mes publicará nuevos materiales bilingües para abordar las preocupaciones de la comunidad sobre las vacunas. La Iniciativa, dijo Mújica, también está impulsando una ordenanza municipal para que sea obligatorio que todos los empleadores coloquen información del Departamento de Salud en los lugares de trabajo, de modo que los trabajadores inmigrantes puedan acceder fácilmente a información objetiva sobre las vacunas.

Mújica sigue haciendo labores de divulgación y educación por su cuenta. El Consulado de México en Chicago le ha invitado a vacunarse en directo por televisión en las próximas semanas. Espera que esto convenza a otros residentes latinos de que las vacunas COVID-19 no sólo son seguras, sino también vitales para su salud y seguridad.

"La vacuna ha sido estudiada. Ha cumplido todos los pasos de cómo se desarrolla una vacuna", dijo Mújica. "Debería ser fácil para la gente obtener la información".

Esta historia forma parte del Soluciones para Chicago esfuerzo de colaboración de las redacciones para cubrir a los trabajadores considerados "esenciales" durante COVID-19 y cómo la pandemia está reconfigurando el trabajo y el empleo.

Esta historia forma parte del Soluciones para Chicago esfuerzo de colaboración de las redacciones para cubrir a los trabajadores considerados "esenciales" durante COVID-19 y cómo la pandemia está reconfigurando el trabajo y el empleo.

Es un proyecto de la Local Media Foundation con el apoyo de la Google News Initiative y la Solutions Journalism Network. Entre los 19 socios se encuentran WBEZ, WTTW, Chicago Reader, Chicago Defender, La Raza, Shaw Media, Block Club Chicago, Borderless Magazine, South Side Weekly, Injustice Watch, Austin Weekly News, Wednesday Journal, Forest Park Review, Riverside Brookfield Landmark, Windy City Times, Hyde Park Herald, Inside Publications, Loop North News, Rebellious Magazine y Chicago Music Guide.