Fotografía de Michelle Kanaar

Fotografía de Michelle Kanaar Tras huir de la guerra, muchos refugiados que llegan a Chicago se enfrentan a nuevos traumas en una ciudad que el año pasado tuvo casi 3.000 víctimas de tiroteos. Pero los servicios sanitarios que antes existían para apoyarles están siendo destripados.

Arriba: Martine SongaSonga, practicante clínica de salud mental en los Servicios Internacionales de Mejora de la Familia, el Adulto y el Niño de Heartland Alliances, fotografiada en IFACES el 11 de noviembre de 2019. Fotografía de Michelle Kanaar.

Cuando Martine SongaSonga entró en su oficina de Uptown una fría mañana de mayo, sus compañeros estaban frenéticos.

"Me preguntaron: '¿Estás bien? ¿De dónde vienes? ¿En qué lado del edificio estabas?'". recuerda SongaSonga. "Yo dije: 'Oh, Dios mío'".

Unos minutos antes de su llegada, un hombre armado abrió fuego cerca de su edificio de oficinas, persiguió a otro hombre por la concurrida calle y le disparó mientras la gente se dirigía al trabajo.

Como terapeuta en un centro de salud mental comunitario que atiende a refugiados en toda la zona de Chicago, SongaSonga estaba acostumbrada a tratar con situaciones traumáticas. Muchos de sus clientes de los Servicios Internacionales de Mejora de la Familia, el Adulto y el Niño (IFACES) de Heartland Alliances habían huido de la guerra o la violencia en su país de origen y sufrían trastorno de estrés postraumático o depresión.

Pero el tiroteo conmocionó a SongaSonga, antigua activista de derechos humanos de la República Democrática del Congo. Para ella y sus clientes, el incidente, así como otros actos de violencia de los que habían sido testigos cerca de sus casas o lugares de trabajo en Chicago, fueron nuevos traumas que desencadenaron algunos de sus peores recuerdos y se sumaron al estrés de intentar empezar de nuevo en un nuevo país que esperaban fuera seguro.

Desde 1999, IFACES ha ayudado a cientos de refugiados con traumas como éstos, así como con graves trastornos emocionales y enfermedades mentales, ofreciéndoles asesoramiento, terapia de grupo y coordinación de cuidados. Aunque la financiación pública de los servicios para refugiados caduca a los cinco años, muchos de los clientes de IFACES llevan acudiendo a la clínica mucho más tiempo, algunos desde su apertura, para recibir servicios de salud mental a bajo coste o gratuitos de personas versadas en temas de refugiados y que hablan su lengua materna.

Pero todo eso está a punto de cambiar. A finales de este año, IFACES cerrará sus puertas. Incapaz de pagar el programa debido a los recortes en la financiación federal para los refugiados bajo la administración Trump, Heartland Alliance cerrará el centro de salud mental el próximo mes. Aunque Heartland Alliance espera que parte del personal y los servicios de IFACES sean absorbidos por sus otros programas, SongaSonga dice que la pérdida para los clientes de IFACES que siguen luchando contra el trauma en Chicago es monumental.

"Es como perder a los padres", dice SongaSonga. "Se sienten abandonados".

***

Martine SongaEl despacho de Songa en IFACES fotografiado el 11 de noviembre de 2019. SongaSonga lleva más de diez años dirigiendo el grupo de apoyo comunitario de IFACES. "Cuando un cliente acude a nosotros también viene con fuerzas. Sí, están rotos, pero tienen activos y fuerza que hacen que la relación de trabajo, la relación de curación, funcione", dice SongaSonga, "es como una flor que se está muriendo y entonces le echas agua y florece". Fotografía de Michelle Kanaar.

IFACES es sólo la última víctima de un creciente número de programas incapaces de sostenerse a sí mismos tras las reducciones gubernamentales de admisiones de refugiados y financiación.

El mes pasado, el Asociación Panafricana cerró sus puertas tras más de una década atendiendo a refugiados africanos y rohingya en la zona de Chicago. La asociación de ayuda mutua, que tenía su sede en el barrio de Edgewater, ayudaba a los refugiados en todos los ámbitos, desde la colocación laboral hasta la educación cívica, pasando por la interpretación de visitas médicas en los meses y años posteriores a su llegada a Estados Unidos.

"Las agencias de reasentamiento te ayudan, pero en algún momento te dicen que te vayas a otro sitio, porque tienen una financiación determinada y un tiempo limitado para prestar servicios a los clientes", explica el director ejecutivo de la Asociación Panafricana, A. Patrick Augustin. "Una agencia de reasentamiento puede atender a un cliente durante dos años, pero al cabo de dos años ¿adónde van los clientes? No tienen otro sitio adonde ir. Así que la mayoría de los africanos han sido derivados a Pan-African Association para que puedan seguir recibiendo servicios."

La mayor parte de la financiación de la Asociación Panafricana procedía del Estado durante los últimos 17 años, dice Augustin, por lo que la organización no pudo continuar sus programas al no recibir este año su subvención regular.

"Se tomó la decisión de cerrar la organización aunque sé que la comunidad sufre mucho", dice Augustin. "Cerramos la oficina, pero todos los días viene gente y llama a las puertas. Esta es la realidad".

El cierre de la Asociación Panafricana sigue al cierre del programa de reasentamiento de refugiados de World Relief Chicago el pasado noviembre. Antes de que el Departamento de Estado cambiara su política de refugiados, WRC reasentaba refugiados en la zona de Chicago desde 1980.

Las principales organizaciones de servicios y reasentamiento de refugiados también han cerrado en ambos países. Milwaukee y Madison en los últimos dos años. A nivel nacional, más de 100 agencias de reasentamiento de refugiados han cerrado sus programas de reasentamiento o suspendido sus servicios de reasentamiento bajo la administración Trump, según el Consejo de Refugiados de EE.UU.una coalición de organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro que aboga por y con los refugiados.

"Los cimientos del programa estadounidense de reasentamiento de refugiados se basan en las relaciones comunitarias que se han fomentado durante décadas", afirma Sarah Seniuk, promoción y comunicación directora del Refugee Council USA. "Estos cierres de oficinas significan no sólo una pérdida de apoyo para los refugiados que han sido reasentados más recientemente, sino que corremos el riesgo de perder algunas de esas relaciones comunitarias, relaciones que son clave para elevar a los refugiados reasentados y asegurar su éxito a medida que construyen nuevas vidas."

Los cierres marcan el final de tres décadas de acumulación de recursos para los refugiados en Estados Unidos, que lideró el mundo en reasentamiento de refugiados entre 1980 -año en que el Congreso promulgó la Ley de refugiados - y 2018. Durante ese periodo, Estados Unidos acogió a 3 millones de los más de 4 millones de refugiados reasentados en todo el mundo, según un análisis del Pew Research Center. Anualmente, Estados Unidos ha reasentado a una media de 95.000 refugiados al año desde 1980.

Pero bajo la administración Trump, las admisiones de refugiados se han reducido drásticamente. Tras asumir el cargo en 2017, el presidente Trump redujo el límite de refugiados a 45.000 para el año fiscal 2018, y luego a 30.000 para el ejercicio 2019. Este otoño, la Casa Blanca anunció otra drástica reducción del 18.000 para el ejercicio 2020, que comenzó en octubre.

En una declaración publicada a principios de este mes, la administración explicó su política de reducción de reasentamientos de refugiados como parte de su "compromiso de tomar decisiones basadas en la realidad, no en deseos, y de impulsar resultados óptimos basados en hechos concretos".

"[L]a crisis humanitaria y de seguridad a lo largo de nuestra frontera sur ha contribuido a una carga en nuestro sistema de inmigración que debe aliviarse antes de que podamos reasentar de nuevo a un gran número de refugiados", reza la declaración. "Por lo tanto, dar prioridad a los casos de los que ya están en nuestro país es simplemente una cuestión de sentido común".

Pero los recortes en las cifras de reasentamiento de refugiados están afectando a los refugiados que ya viven en Estados Unidos, además de a los que intentan venir aquí.

Las organizaciones que apoyan a los refugiados en Estados Unidos se financian con una mezcla de fondos federales, estatales y privados. Heartland Alliance, por ejemplo, recibe fondos del Departamento de Estado. Oficina de Población, Migración y Refugiados así como a través del Oficina de Reasentamiento de Refugiados (ORR), que envía dinero tanto a través de Springfield como directamente a las agencias de servicios. La financiación estatal de la ORR -que cubre todo, desde apoyo al empleo hasta gestión de casos y servicios de salud mental- se determina en función de las llegadas del año anterior.

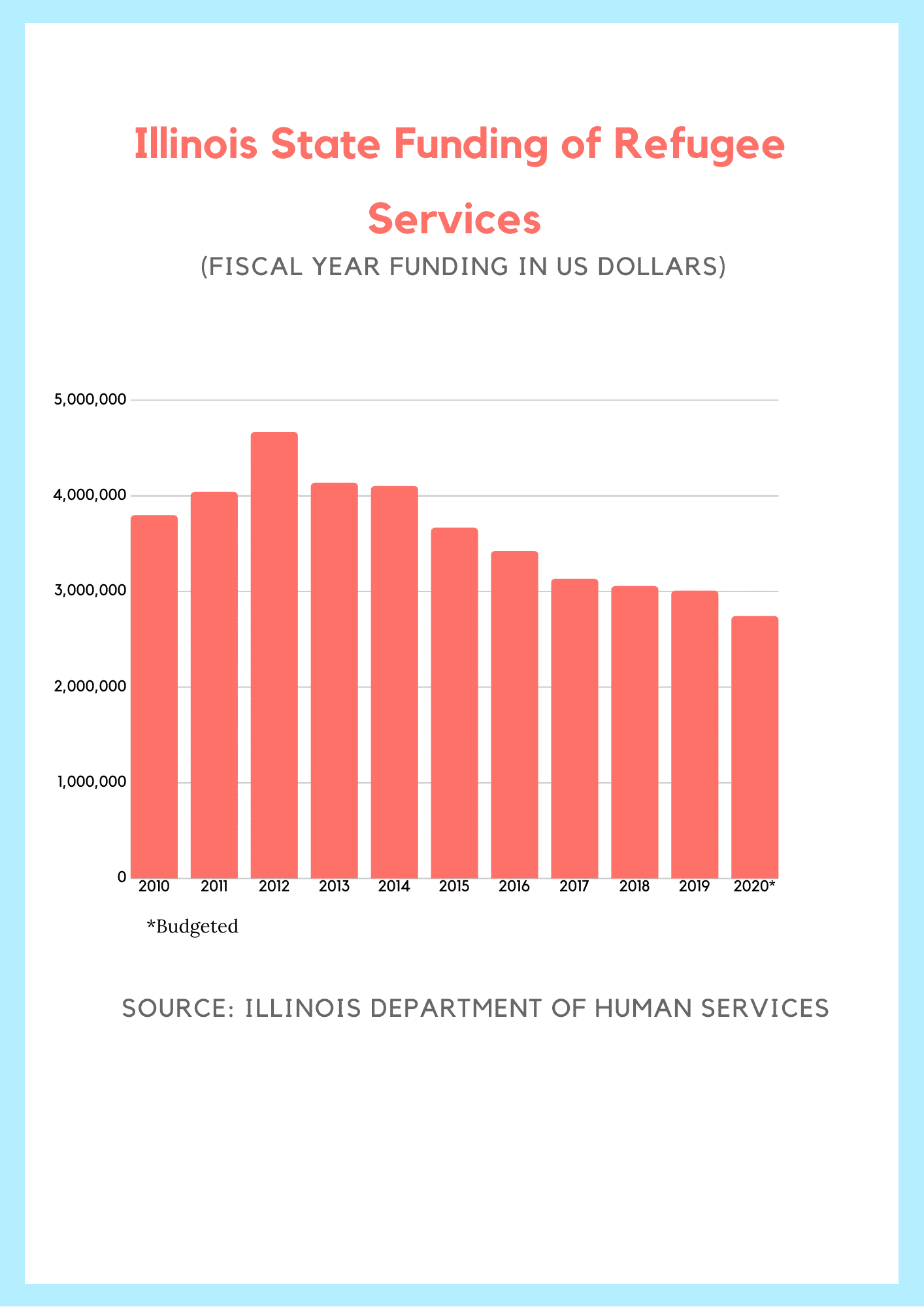

Las admisiones de refugiados a Illinois han disminuido de 3,045 refugiados que vinieron aquí en el año fiscal estatal 2017 a solo 885 refugiados que vienen aquí en el año fiscal estatal 2019, una caída del 70 por ciento. La financiación para los refugiados a nivel estatal también ha experimentado una disminución dramática. Mientras que Illinois gastó $4,6 millones en servicios para refugiados en el año fiscal estatal 2012, el estado tiene presupuestado gastar solo $2,7 millones en servicios para refugiados para el año fiscal estatal 2020, que comenzó este mes de julio.

"En los programas para refugiados, cada seis meses más o menos parece que recibimos algún otro tipo de recorte", dice Amy Dix, directora clínica de IFACES. "Nos está afectando mucho".

Al mismo tiempo, IFACES siguió atendiendo a refugiados que llevan años aquí y necesitan apoyo continuo para problemas de salud mental, que a menudo no se manifiestan hasta que se pasa el shock de estar aquí.

"Un número muy pequeño de personas recibe algunos servicios de salud mental antes de llegar o se identificó algo como un diagnóstico de TEPT", dice Dix. "Una vez que se sienten un poco más estables y saben lo que hacen aquí, a veces vuelven los recuerdos y es entonces cuando se produce una reacción de TEPT".

Factores estresantes como la violencia armada, el elevado coste de la vida y el intento de aprender inglés pueden agravar estos problemas, haciendo aún más acuciante la necesidad de una atención sanitaria continuada.

***

Una tarde reciente, el Dr. Gary Kaufman hizo una pausa en su apretada agenda de citas para dar una vuelta por el museo. Centro Médico Familiar Antillas del Sistema de Salud Sinaí en Logan Square, donde ejerce de director médico. Más allá de la abarrotada sala de espera, donde las familias llenan las sillas y algunas se sientan en el suelo, Kaufman muestra la vía principal de la estrecha clínica: un pasillo de puertas etiquetadas cada una con una especialidad médica. Cinco días a la semana, médicos especializados en todo tipo de especialidades, desde medicina interna y psiquiatría hasta ginecología y odontología, vienen a ver a los pacientes.

"Bienvenidos a la mayor clínica de detección de refugiados del estado de Illinois", dice Kaufman.

A pesar de su actividad actual, la clínica es también una sombra de lo que fue.

Fundada en 1973 en el barrio de Rogers Park con el nombre de Touhy Health Center, la clínica atendió inicialmente a la afluencia de refugiados rusos que se estaban asentando en la zona en aquella época. El estado de Illinois contrató a Mount Sinai en aquellos primeros días para llevar a cabo el reconocimiento médico obligatorio al que debían someterse todos los refugiados poco después de llegar a Estados Unidos.

Aunque muchos de aquellos primeros pacientes rusos siguieron acudiendo a la clínica por necesidades sanitarias mucho más allá de aquel reconocimiento, cuando Kaufman se incorporó a Touhy como médico recién salido de la residencia en septiembre de 2000, la población de la clínica cambió y creció con los conflictos mundiales. Trató a bosnios y albaneses, luego a somalíes y afganos, y a congoleños y rohingyas.

La clínica también creó una red de organizaciones de refugiados y voluntarios que podían ayudar a informar a Kaufman y sus colegas de los problemas de salud a los que se enfrentaban los refugiados que llegaban y garantizar que, una vez en Estados Unidos, esos refugiados recibieran la atención médica continuada que necesitaban, recordándoles sus citas y traduciéndoles si era necesario.

En 2016, el Centro de Salud Touhy atendía a más de 2.000 refugiados al año solo para su examen de detección obligatorio.

Entonces, ocurrieron las elecciones.

"Recibíamos 120 o 130 refugiados cada mes fácilmente", dice Kaufaman. "Ahora recibimos 30".

El doctor Gary Kaufman, director médico del Centro Médico Familiar Antillas de Sinai Health System en Logan Square, en una imagen en una sala de exámenes el 8 de noviembre de 2019. Foto de Nissa Rhee.

De la noche a la mañana, el número de refugiados admitidos en Estados Unidos se redujo y el estado de Illinois decidió recortar la subvención administrativa que concedía al Sinaí para pagar al personal de apoyo que mantenía la clínica en funcionamiento y el laborioso mantenimiento de los historiales médicos de los refugiados que exigía el gobierno.

Incapaz de encontrar los $800.000 necesarios para mantener la clínica en funcionamiento, El Sinaí anunció el cierre de Touhy en octubre del año pasado.. En enero, el Sinaí trasladó los principales servicios para refugiados de Touhy a su actual clínica de Antillas. Kaufman pudo conservar a los miembros más importantes de su equipo para el programa, pero el grupo se redujo de una plantilla de 18 a siete personas. Su antiguo equipo hablaba 25 idiomas en casa; ahora hablan 10.

Aunque Kaufman también pudo conseguir una furgoneta para recoger a los pacientes refugiados que viven en el extremo norte y llevarlos a Logan Square, afirma que algunos de sus pacientes no han podido hacer el trayecto.

"Tengo una familia de 15 hijos, una familia de refugiados en la que la mamá no haría nada sin que yo lo aprobara. Como ir al hospital. No a menos que el Dr. Kaufman lo dijera. Pero ella dijo: 'No puedo hacerlo, es demasiado lejos. No puedo ir y volver y estar en casa para que los niños vayan al colegio'", dice Kaufman. "Eran personas que realmente confiaban en nosotros y nos querían. Eso ocurría a menudo. La gente quería quedarse con nosotros y sabían que les atendíamos bien y que éramos alguien que entendía lo que significa ser refugiado, pero no podían por la distancia".

Kaufman teme cuáles serán las consecuencias a largo plazo de la reducción de la red de servicios para los refugiados en los próximos años, especialmente para los que sufren problemas de salud mental. Aunque su clínica cuenta con una psiquiatra que atiende a los pacientes algunos días al mes, sus citas se agotan con meses de antelación. Kaufman solía confiar en IFACES para suplir algunas de esas carencias, pero pronto tendrá que buscar alternativas. Los conocimientos institucionales y el apoyo que el Sinaí, IFACES y otros organismos han prestado a los refugiados durante décadas están ahora en peligro.

"Tenemos contratos estatales desde hace 40 años para hacer esto", dice Kaufman. "Tenemos mucha experiencia en saber cómo atender a los refugiados porque llevamos mucho tiempo haciéndolo. Actualmente no hay nadie más en Chicago que haga esto".

***

En octubre, en su pequeño despacho de la cuarta planta del edificio del Instituto de Asuntos Culturales del Uptown, Martine SongaSonga hojeaba un cuaderno de espiral donde anotaba las notas de las últimas sesiones de sus clientes.

El pasado ejercicio, IFACES atendió a 238 personas. Cuando el programa cierre el mes que viene y sea sustituido por un programa de coordinación de cuidados en Heartland Alliance, Dix calcula que podrán atender a la mitad de clientes. En lugar de ver a los terapeutas en una clínica independiente centrada en los refugiados, los clientes se pondrán en contacto con los terapeutas a través del centro de salud federalmente cualificado de Heartland Alliance.

Para SongaSonga, el proceso de despedirse de sus clientes ha sido emotivo.

"Intento decirlo con sus propias palabras", dice SongaSonga consultando su cuaderno.

"'Hemos aprendido mucho de vosotros y hemos tomado lo aprendido para intentar animar a otros recién llegados'.

Me apoyáis para que pueda apoyar a mi hija y estar a su lado. No sabemos lo que seríamos sin este programa'.

Estoy vivo aquí gracias a ti. Tú me motivas a ser fuerte y estar vivo'".

El último día de SongaSonga en IFACES será el mes que viene. Espera seguir trabajando con refugiados o solicitantes de asilo en otro programa de Heartland Alliance en Chicago el año que viene. A pesar de la pérdida del programa, se muestra optimista sobre el futuro.

"Creo que la vida es dinámica, no es estática", dice SongaSonga. Aunque el cambio puede ser difícil, merece la pena porque evolucionamos. Es duro. Pero es un proceso por el que tenemos que pasar. No podemos seguir siendo los mismos".

¿Le han afectado los recortes en la financiación de los refugiados? Póngase en contacto con nosotros en [email protected].

El apoyo a esta historia vino del Fundación Chicago Headline Club.

Borderless Magazine es su fuente de historias que trascienden fronteras. Usted puede apoye nuestro trabajo con una donación libre de impuestos hoy mismo.