El fotógrafo Omar Imam habla de lo que significa ser un refugiado sirio seis años después de un conflicto que ha dispersado a los sirios por todo el mundo.

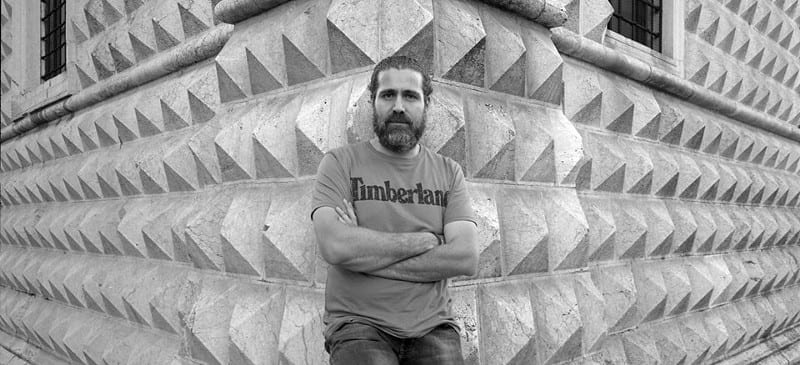

Arriba: Omar Imam. Foto de Omar Imam

Fotógrafo Omar Imam abandonó su Damasco natal en 2012 y ahora reside en los Países Bajos. En una entrevista con 90 días, 90 voces, Imam habló de lo que significa ser un refugiado sirio seis años después de un conflicto que ha dispersado a los sirios por todo el mundo. Su última serie fotográfica, "Vivir, amar, refugiadodeja de lado las estadísticas del desplazamiento y se centra en los sueños, esperanzas, humor y realidades de la experiencia de los refugiados.

Imam es el destinatario del Premio Visionario 2017 del Tim Hetherington Trust y un premio de la Fundación Magnum 2014 Programa de Fotografía Documental Árabe becario. No pudo asistir a su primera exposición en Chicago, en la Catherine Edelman Gallery, el 14 de julio, debido a las restricciones de visado impuestas a los sirios que viajan a EE.UU. Para hablar de "Live, Love, Refugee" con Sin fronteras, Imam utilizó la aplicación de mensajería WhatsApp.

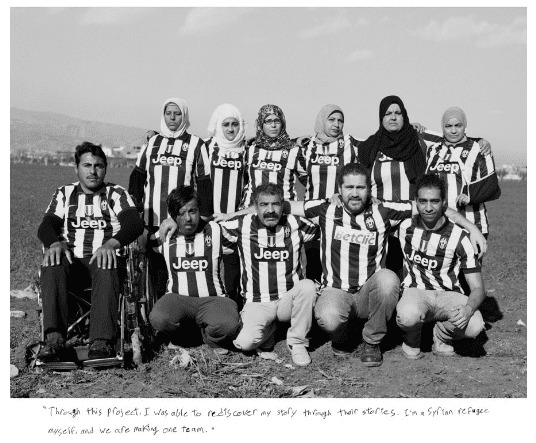

Quería descubrirme como siria, artista y activista a través de mis fotografías en "Live, Love, Refugee". Ya sabía mucho sobre lo que está ocurriendo en Siria, pero al hablar con sirios de distintas ciudades me di cuenta de que en realidad sabía muy poco. Con cada historia, descubrí que quería saber más. De lo que no nos damos cuenta es de que hay seis millones de historias en el mundo esperando a ser contadas.

No llegué a este proyecto con un mensaje político, aunque tengo mis propias opiniones políticas. Intenté alejarme de la política y centrarme en el lado humano de este conflicto. La gente se divide en los conflictos: los que están armados y los que no lo están. Mi trabajo pone en tela de juicio la representación que hacen los medios de comunicación de estos últimos, que en mi opinión son los que llevan el peso del conflicto sirio.

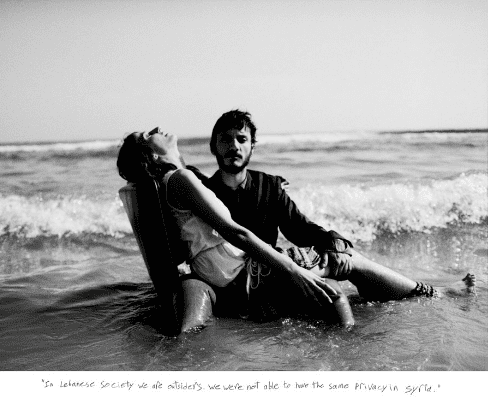

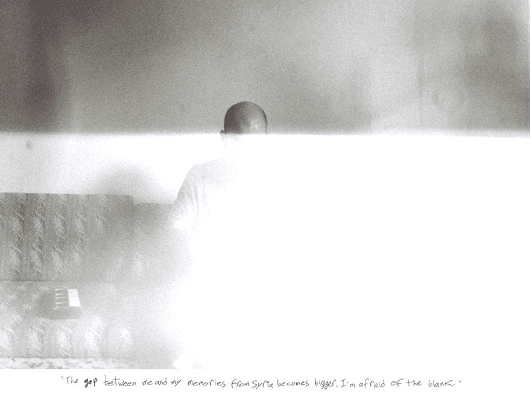

Quería reimaginar la imagen del refugiado. Este tropo tiene una representación casi intemporal en las fotografías. Es un cierto tipo de imaginería que ha funcionado durante los últimos 100 años, no sólo ahora. Para mí, los refugiados sirios en el Mediterráneo se parecen a los refugiados de hace 20 o 30 años, y aquellos refugiados se parecían a los de la Primera Guerra Mundial. Quizá necesitemos un respiro para replantearnos nuestra imagen de lo que es un refugiado.

Creo que los periodistas pueden replantearse todo el proceso de sus misiones y pasar más tiempo con las comunidades que cubren. Me he dado cuenta de que pasan un día en un campamento del norte de Líbano y, al cabo de tres días, visitan cuatro o cinco campamentos distintos y dedican unos 20 o 30 minutos a cada persona. He pasado nueve o diez meses hablando con la gente y sólo he sacado 11 fotos. Así es como yo trabajo, y no pido a los periodistas que hagan lo mismo, pero quizá puedan intentar ser más humanos en su punto de vista.

Si quieres entender mejor la vida de los demás, puedes hacerlo. A veces, para la logística es desalentador: hace mucho frío y hay mucho barro en los campamentos, y hueles a enfermedad por todas partes. No hablas su idioma. A veces vas con tu cámara y sin traductor, así que no hay una relación real con el personaje, simplemente ellos están allí y tú estás allí. No quiero ser duro con los periodistas. Pero hay formas de humanizar la imagen del refugiado y no limitarse a ser una víctima.

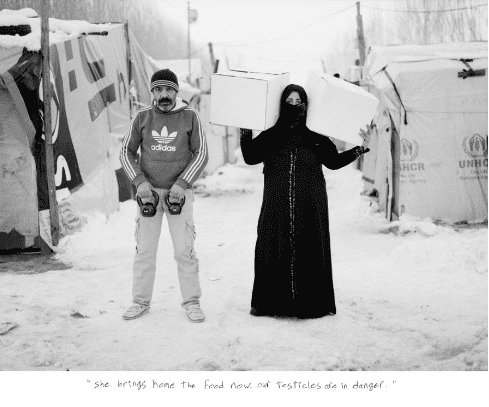

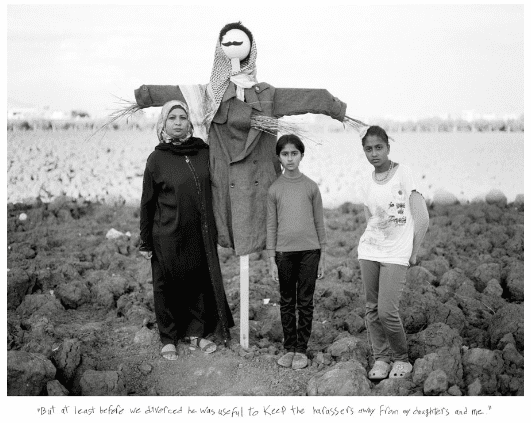

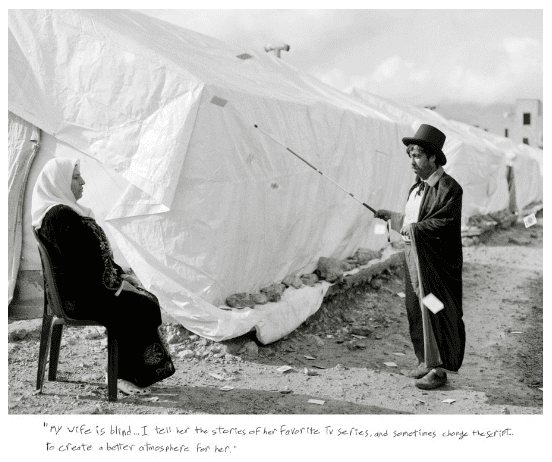

Los refugiados son víctimas literales. El reto para mí era cómo no mostrarlos como víctimas en las fotografías. Como artista, victimizar a los refugiados es lo más fácil. Mis fotografías tratan de víctimas, pero las muestro con dignidad y me centro en su actitud de supervivencia. En el campo me di cuenta de que, por muy mal que estuvieran las cosas, muchos de los refugiados no perdían el sentido del humor. Supongo que para los sirios, el sentido del humor es la forma en que hemos sobrevivido a todo esto.

Me mudé al Líbano en noviembre de 2013 a una casa que alquilé yo misma. No estaba familiarizada con la vida en los campamentos, y así es como surgió toda la idea de "Live, Love, Refugee". Cuando fui a los campamentos me di cuenta de que si alguna ONG venía ese día, se limitaban a contar el número de personas para repartir mantas o alimentos, pero nunca hablaban realmente con ellos. Incluso si hablaban, los refugiados veían a los cooperantes, o incluso a un sirio como yo, como extraños. Cualquiera que viva fuera del campo es un extraño. Así que el campo empezó a representar historias desconocidas para mí.

En general me acogieron bien, pero el reto era cómo presentar el trabajo documental conceptual. Para ellos, cualquiera que tenga una cámara es la CNN o Al Jazeera. Así que existe una relación muy estereotipada con los medios de comunicación. Cuando los refugiados del campo veían a un periodista o a un cámara, enseguida empezaban a describir lo mal que les iba la vida y que no recibían suficiente dinero de ACNUR. Es una forma de sobrevivir a las condiciones en las que viven. A menudo la gente realmente necesita dinero para una operación o comida extra o mantas. Pero yo quería ayudarles a ir más allá de la victimización [y a] contar sus propios sueños. Fui paciente y les describí lo que era la fotografía conceptual, les dije que escucharía su historia y que juntos la convertiríamos en un buen proyecto visual.

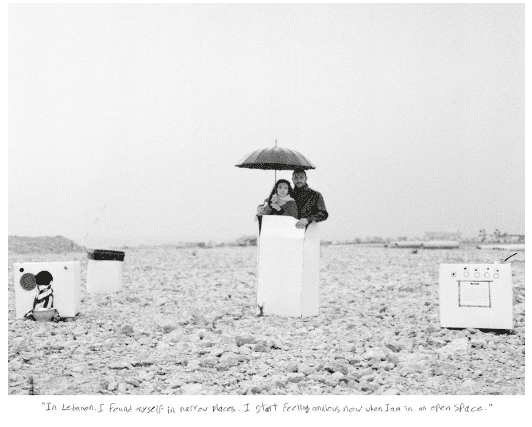

Fue difícil porque en Siria tenemos culturas diferentes. La mayoría de los refugiados de los campos procedían del campo, donde tenían menos acceso al arte, así que fue difícil convencerles de que se unieran a este proyecto, pero al mismo tiempo la vida en el campo les hizo más abiertos a nuevas ideas. La mayoría ya había sufrido las consecuencias de la guerra, así que no les importaba probar algo diferente: ya había ocurrido un terremoto en sus vidas.

Cuando empecé con el proceso, para la mayoría fue alegre, lúdico, incluso terapéutico. A algunos les gustó, pero otros no pudieron romper la imagen estereotipada de lo que una cámara desencadenaba en su cerebro sobre los medios de comunicación. Es curioso que el público de todo el mundo esté acostumbrado a esta imagen trágica de los refugiados: la anciana en el frío o el niño en el barro. No digo que esas imágenes no sean ciertas, pero es sólo una capa de sus vidas cuando hay muchas otras capas. Es curioso que no sólo el público, sino los propios refugiados se hayan creído esa imagen de cómo debe ser un refugiado ante una cámara.

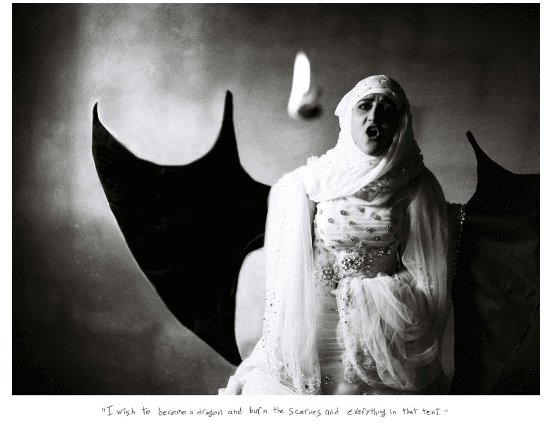

Cada fotografía empezaba con horas aprendiendo sus historias y preguntándoles si les parecía bien hablar de una idea concreta. Si la respuesta era afirmativa, me iba a casa y, como artista, me ponía a pensar en cómo plasmarla visualmente con atrezo, y luego me ponía en contacto con ellos por WhatsApp para decirles, por ejemplo: "Este es el concepto: tú serás un dragón". La mayoría de las veces les parecía bien, [pero] si no, tenía que desarrollarlo más. Luego volvía al campamento para rodar. Lo que más disfrutaban era el rodaje. Los personajes y sus vecinos participaron en la dirección artística y la puesta en escena de estas fotografías. Parecía un poco teatro.

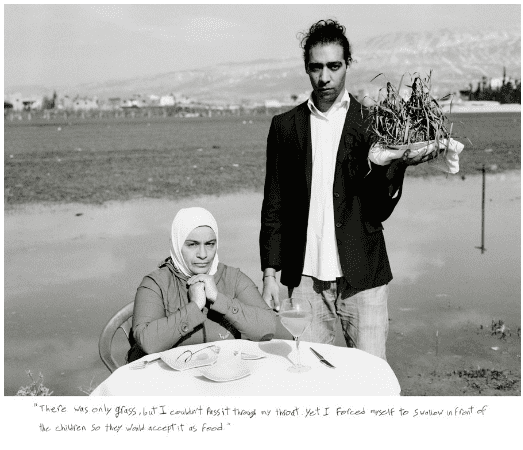

Uno de mis sujetos favoritos era Amina. Tengo dos fotos de ella: una entre dos tiendas con auriculares que dice: "Tenía miedo cuando hay calma. Comprueban quién ha muerto y quién está herido... Me sentía más segura cuando escuchaba música". En otra, imitamos un restaurante con un camarero al lado de Amina sosteniendo un plato de hierba. Compartió muchas cosas conmigo: en Yarmouk ocurrieron muchos crímenes. Había perdido unos 70 kilos por inanición.

A veces nos sentábamos juntas y ella me contaba sus historias. Físicamente había recuperado peso, pero sus huesos se habían vuelto muy blandos por el hambre. Si llevaba una bolsa de patatas de 4 kilos, a veces se le doblaban con el peso. Recuerdo que le pregunté si alguno de los combatientes había muerto de hambre en su zona. No, me dijo, ninguno. Son más rápidos y están mejor equipados para sobrevivir a todo este caos que los civiles, pero los civiles como Amina soportan las cargas más pesadas de la guerra.

Mi foto favorita es la de la pareja en la nieve con los destornilladores volando. El hombre está en silla de ruedas junto a su mujer. Trabajar con esta familia fue la experiencia que más me marcó durante el proyecto. Fueron los que más sufrieron de todos. Perdieron a su hijo y a su hija de 4 años. Sólo la esposa había perdido a sus tres hermanos y a su madre durante la guerra, y al marido lo empujaron desde el cuarto piso de un edificio en el Líbano. Para mí, cargaban con mucho dolor, demasiado dolor.

Pero lo más aterrador fue que cuando me contaron su historia no había lágrimas ni rabia, sólo una expresión muy sencilla en sus rostros. Fueron la primera pareja que pasó del dolor a un espacio de no sentir más. Especialmente la esposa, que sonreía cuando describía lo que les había ocurrido. Al principio, no sabía cómo afrontarlo. Mi asistente y yo volvíamos a casa en silencio por haber experimentado demasiado los días que hablábamos con ellos.

Imagina que esto fuera sólo una historia en una tienda de campaña en un pequeño campamento en un pequeño pueblo del Líbano. Si escucharas todas las historias de los seis millones de sirios desplazados, ¿qué encontrarías? ¿Qué podríamos aprender de sus historias?

Al mismo tiempo que hacía este trabajo, tenía que protegerme mientras escuchaba sus traumas porque necesitaba oír sus historias. No impediría a ningún personaje contar lo que quisiera. Como artista, se trata de respetarlos a ellos y a sus experiencias, que incluyen lo doloroso y lo bello. Al final, me convertí en un cirujano, abriendo un cuerpo mientras veía un partido de fútbol.

Incluso en mi caso, no me gusta ser la víctima. Ser torturado influyó en mi carrera. En primer lugar, creó más conceptos en mi mente. Podría decirse que enriqueció mi imaginación. La milicia que me torturó era muy creativa en cuanto a lo malos que podían ser, y les admiro por ello. Me influyó en cómo puedes mostrarte y cuántas capas e ideas puedes poner en una composición, en una foto. Fue divertido lo que me pasó de una manera cínica, cuando pienso en lo extraño que es que te secuestren. Pero no, no aconsejo a otros artistas que pasen por la tortura para expandir su arte.

A nivel personal, a través de mi propia experiencia, me ayudó a entender las experiencias de los demás y a creer en sus historias por extrañas que parezcan. Descubrí que, como humanos, nos entrenamos para proteger nuestras propias creencias: pensamos que esto es tan extraño que no puede haber ocurrido.

Eso es lo que me ocurrió en los primeros años, los sirios o amigos tenían una actitud defensiva cuando compartía con ellos mi historia de secuestro y tortura.

Yo diría, ¿qué pruebas necesitas? Sólo cuento mis historias. A medida que seguía contando mis historias, me volví más abierta. En cierto sentido, eso me daba ventaja cuando los refugiados también compartían sus historias conmigo. A veces me miraban y me decían: "Eres sirio, pero vienes de un buen barrio de Damasco. Eres artista. Puede que no nos entiendas. Puede que no entiendas lo que se siente al ser torturado en las cárceles". Yo les decía: "Puede que yo no haya sufrido lo mismo que tú", y les contaba parte de mi historia. Después, me decían: "Sabemos que sientes lo mismo que nosotros".

Creo que existe una similitud entre la experiencia de los refugiados y la tortura: Si uno mismo no ha sido torturado, se pierde cierta sensación cuando un superviviente cuenta su historia. Nunca podrás entender realmente lo que se siente al ser torturado, o al ser refugiado, a menos que vivas esa experiencia.

En mi caso, no tengo ningún sentimiento hacia los que me torturaron. No los amo, ni los odio. Nunca busqué justicia en mi caso porque estaba bastante seguro de que no habría justicia en este caso, como en muchos otros. Muchas personas me prometieron justicia, pero nunca la obtuve.

Sólo quería irme de aquel lugar. Me dije que no pensara en ellos desde una perspectiva personal porque la venganza dañaría mi cerebro. Me dañaron a nivel físico, pero mantuve mi alma limpia de querer vengarme. Puedo entender lo que pasó: No lo apruebo, no me gusta, pero cuando miras esta experiencia cuando estás fuera de Siria con muchos años entre tú y esta experiencia, es sólo una consecuencia lógica del conflicto.

Más información sobre la obra "Live, Love, Refugee" de Omar Imam, que forma parte de la exposición "Targeted" de la galería Catherine Edelman de Chicago. Esta entrevista ha sido editada para mayor extensión y claridad.