After applying for deportation relief in a Chicago suburb, an undocumented immigrant from Mexico faces anti-immigration policies and bureaucratic delays.

Above: Jesus Santos at a park near his home on Jan. 8, 2021 in North Riverside, Ill. Samantha Cabrera Friend for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local Chicago

In the spring of 2015, Jesus Santos walked into the Immigration and Customs Enforcement office in Oakbrook Terrace to turn himself in to authorities.

It was a risky move for an undocumented immigrant. But the 46-year-old father of three, who has lived in America since he was 15, had few other options.

Applying for asylum would be nearly impossible: Although his hometown of Guerrero, Mexico, is plagued by street gangs and armed guerrilla groups, he cannot prove that he would face danger if he goes back. Santos could theoretically wait for his oldest child — a U.S. citizen — to turn 21, and then apply for a green card as an immediate relative, but he would have to first return to Mexico and wait there for at least 10 years.

By placing himself in deportation proceedings, Santos could apply to adjust his status and possibly attain a green card through a benefit known as cancellation of removal.

“I know this was a big risk, but I just don’t want to live in the shadows anymore,” said Santos, who lives with his wife and children in Riverside, a suburban village outside Chicago. “I used to be nervous all the time. If everything goes well, I’d like to push a reset button and start all over again.”

But Santos’ long journey to legal residence was only beginning. Applying for cancellation of removal — a type of deportation relief that adjusts an immigrant’s status from “deportable” to “lawfully admitted for permanent residence” — has never been swift or easy. Its legal provisions are so obscure and its eligibility requirements so demanding that only 6.5 percent of the more than one million immigrants who entered into deportation proceedings in the past four years applied for the benefit, according to data from Syracuse University’s Transactional Access Records Clearinghouse (TRAC).

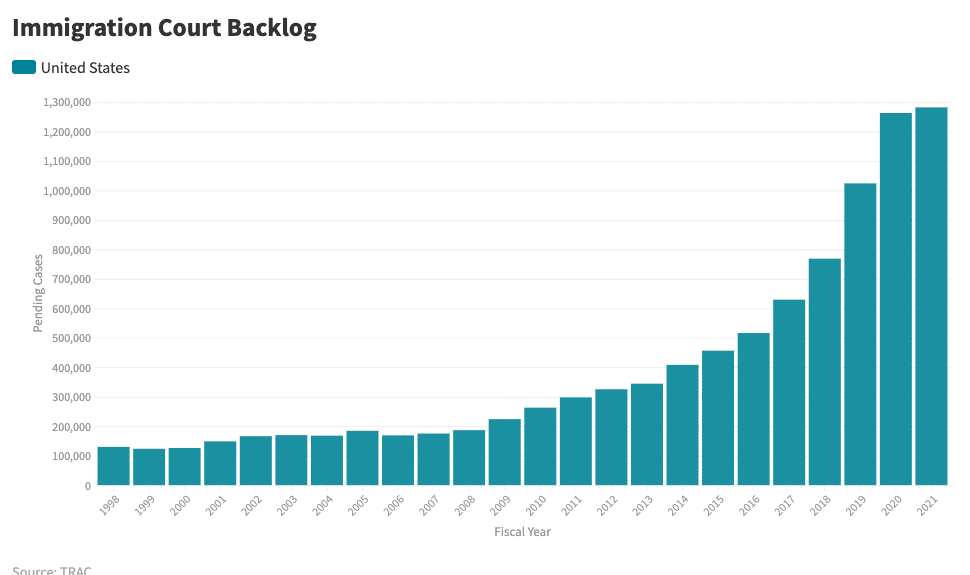

The process has only worsened under the Trump administration and during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has strained the court system and placed many cases for non-detained immigrants on hold. With the largest immigration court backlog on record and heightened political pressure on judges to deliver deportations, the odds are increasingly stacked against applicants.

“Cancellation of removal is pretty specific and pretty restrictive, and it just doesn’t apply to a whole lot of people,” said Austin Kocher, a faculty fellow at TRAC. “And many people just don’t know about it because they may not have a good immigration attorney, or they may not have an immigration attorney at all.”

Currently, only one out of four immigrants is represented in their deportation proceeding, according to data compiled by TRAC. Last year, those who were unrepresented faced a deportation rate of 82 percent, compared with 19 percent for those with attorneys.

Long wait times also deter immigrants from applying for cancellation. On one hand, Kocher said, applicants have more time to prepare their documents and raise money for their legal fees, which usually cost thousands of dollars. On the other hand, both the applicant’s personal situation and the national guidance on a specific form of relief could change over a long period of time. Besides adding to applicants’ anxiety, the delays could also impact final case decisions.

A judge could theoretically process a well-prepared case like Santos’ within a week, according to Denise Slavin, a former immigration judge. But the current administration has been prioritizing cases concerning recent border-crossers, unaccompanied children and undocumented immigrants with criminal records. Cancellation cases, Slavin said, often remain buried in the backlogs. Santos, for instance, has friends in similar situations who have been waiting for more than 10 years to get their applications processed.

Under Trump, the immigration court system has been overwhelmed by a surge of new deportation cases, and the number of backlogged cases has skyrocketed by 160 percent to a historic high of more than 1.2 million, TRAC data shows. Nationally, the average wait length for a deportation case has nearly doubled from 447 to 849 days in the past decade. Cancellation cases, specifically, can easily stretch over five years, experts said.

Aside from the sheer number of deportation cases that require processing, the Trump administration’s politicization of the immigration court system also exacerbated delays. Shortly after Trump’s inauguration, the Department of Justice sent Slavin and three other judges to the border to hear the cases of recent border-crossers. But it was just a “a dog and pony show to impress the public,” Slavin said. In reality, she had to postpone about 200 cases on her regular docket and heard only seven cases on the trip.

“The current administration is forcing us to schedule cases by their law enforcement priorities instead of when the case is ready to be heard,” Slavin said. “I had less and less control under this administration and was more and more considered an employee as opposed to a judge.” Fed up with the daily pressure from the Department of Justice to deport as many immigrants as possible, she retired last April after 24 years on the bench.

Winning a cancellation case is an uphill battle. The Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 created the legal provision for cancellation of removal to replace a similar type of relief known as suspension of deportation, after then-Senators Spencer Abraham (R-Mich.) and Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) argued that immigration judges were granting discretionary relief too freely. Applicants previously had to demonstrate that their removal would bring “extreme hardship” to either themselves or their family; the replacement statute requires proof of “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to an immediate family member who is either a U.S. citizen or a permanent resident. Under the current law, immigrants will also be disqualified if they are convicted of certain crimes, from drug possession to false claims of U.S. citizenship.

According to Alberto Benítez, the director of the Immigration Clinic at George Washington University Law School, winning a suspension case for his clients before 1996 was challenging enough. But the new language, he said, was deliberately written to further restrict the number of qualified applicants.

“Congress specifically did it this way to make the process as unpleasant, as harmful and as drastic as possible,” Benítez said.

Santos met the hardship standard because of his 20-year-old daughter Ximena, who was born with a severe heart defect. She has undergone five surgeries and still visits her doctors at least once a month.

Jesus Santos and his daughter Ximena Santos, 20, at a park near their home on Jan. 8, 2021 in North Riverside, Ill. Samantha Cabrera Friend for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local Chicago

It would be impossible, Santos argued, to take care of Ximena and pay for her continuous treatments if he returns to Mexico. But after Ximena turns 21 next year, she can no longer be a part of Santos’ cancellation of removal case and the chance of him getting approved would be exponentially lower.

The Chicago Immigration Court initially scheduled Santos’ trial for March 2020 — already more than five years after the initial filing — but ended up pushing back the date three times due to the ongoing pandemic. When Santos received a letter informing him of his new trial date in 2024, he panicked.

“I know it’s not easy. There’re a lot of people like us on the waiting list,” Santos said. “But four more years is still a long, long time. When my kid turns 21, my case is over. ”

Unlike Santos’ attorney, many lawyers are reluctant to recommend their clients to enter deportation proceedings just to apply for cancellation. Colorado-based immigration attorney Daniel Kowalski said he has never taken on a case like Santos’ during his 35 years representing clients in the immigration system. Not knowing which judge or government prosecutor the applicant is going to get, he said, is too big a risk.

“The reason why more lawyers don’t do it is because they don’t want to gamble on getting a bad judge,” said Kowalski, who also serves as editor-in-chief of Bender’s Immigration Bulletin. “And the standard is so high that even if they won, the government could still appeal, and then they’d be tied up in the appeal for years.”

The risk has become even higher in recent years as the Trump administration filled the immigration court system with hardline judges, according to Paul Schmidt, a former judge at the U.S. Immigration Court in Arlington, Virginia. For years, legal groups have urged the government to hire judges from diverse backgrounds to guarantee fairness in the courts, but the situation has only deteriorated in recent years, Schmidt said.

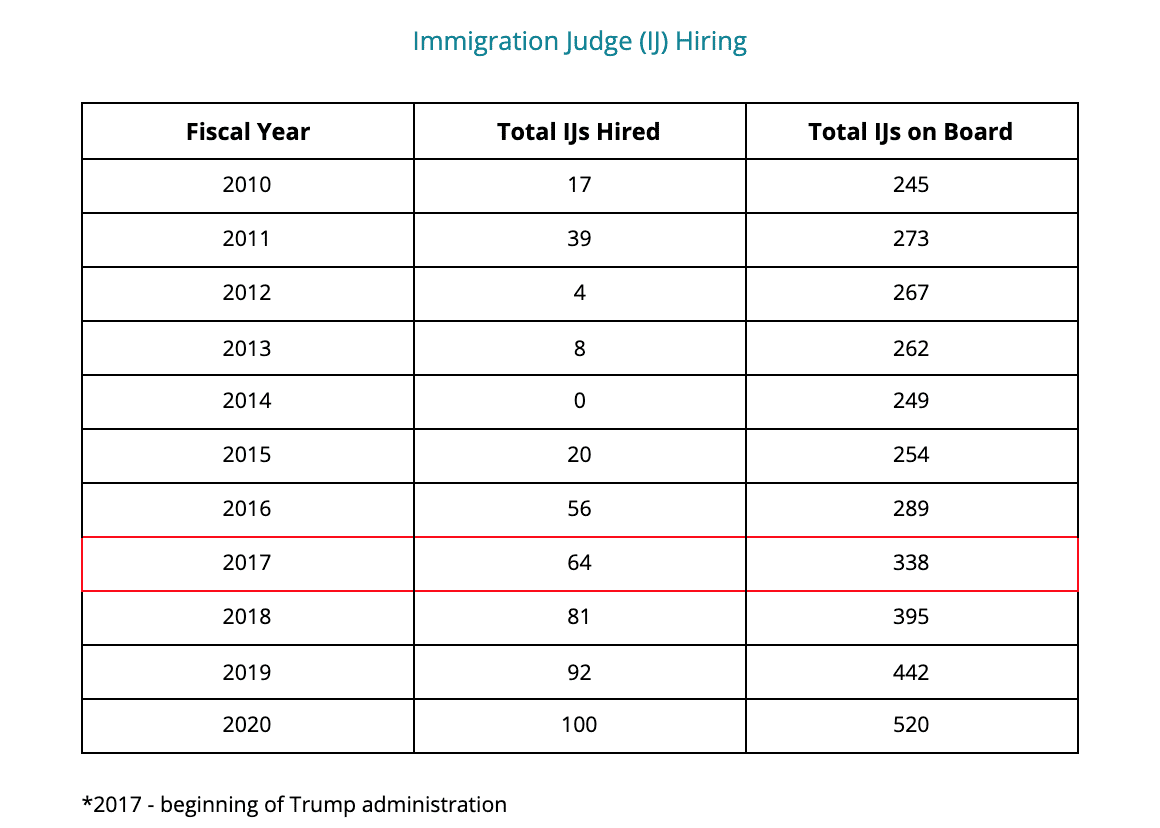

Source: Department of Justice

After Trump took office four years ago, he dramatically expanded the size of the immigration bench from 306 to 520 by October 2020. By comparison, there were an average of 258 immigration judges working in the United States in fiscal years 2010 through 2015 according to the Department of Justice.

“The Obama administration was just negligent,” Schmidt said, suspecting that former president Barack Obama left dozens of vacant immigration judgeships when left the White House. “The new administration got a chance to fill those positions with a far-right judiciary.”

A majority of the new appointees came from law enforcement backgrounds and are more likely to make decisions biased toward government prosecutors. A report by nonprofit Human Rights First found that 88 percent of immigration judges appointed in 2018 were either former Department of Homeland Security attorneys who prosecuted immigration cases or other government attorneys. As the judges take on a harsher stance on immigration, the denial rate for asylum cases has risen consistently from 55 percent in 2016 to the current rate of 72 percent, TRAC found.

“It’s very much a law enforcement-oriented and not a due process-oriented judiciary,” Schmidt said. “It’s just a bad time to be an individual with a case in the immigration court right now, with a bunch of unsympathetic judges, political hacks pulling the strings, and inconsistent COVID policies.”

Fortunately for Santos, his lawyer negotiated successfully with the court to expedite his trial.

Jesus Santos at a park near his home on Jan. 8, 2021 in North Riverside, Ill. Santos holds the notebook he has used to keep notes of his citizenship case, in his years-long attempt to adjust his status and possibly attain a green card through a benefit known as cancellation of removal. Samantha Cabrera Friend for Borderless Magazine/CatchLight Local Chicago

On Nov. 12, he arrived at the Chicago Immigration Court with his wife and daughter. Holding a brown journal filled with notes, he paced the hallway as he awaited the hearing that would decide the fate of him and his family.

When his trial was called, Santos quietly entered the courtroom, sat in front of the judge, and put on a headset so that the interpreter could translate the inquiries into Spanish. Like many cases held during COVID-19, the attorney for the Department of Homeland Security joined the hearing via teleconference. Testifying while wearing a mask, Santos spoke about his immigration history and the disastrous consequences that his departure would have for his family.

At the end of the one-and-a-half-hour hearing, the judge said that he was leaning toward a favorable ruling, but that Santos would have to wait 18 to 24 months before receiving a formal decision. Such a statement usually means that the judge has unofficially approved the application, according to Santos’ lawyer Omar Abuzir.

That night, Santos ordered hamburgers for his children. After five excruciating years of waiting, he felt that his family deserved this moment of relief.

“I didn’t know this would be such a long time,” Santos said. “It was very, very hard for me because I want to do a lot of things. I’m going to buy a house for my family, and I’ll help my children go to college.”